Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen’s Geordie beaches

Originally published 25 years ago, the revised and expanded edition of Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen’s Writing in the Sand from Dewi Lewis Publishing reintroduces the lively, eccentric spirit of Geordie beachgoers into the present. With a deft balance of nostalgia and immediacy, Michael Grieve writes that Konttinen’s photographs not only celebrate the quirky nuances and contradictions of working-class life but also reveal an awkward yet tender relationship with the beach – a place both distant and intimate.

Michael Grieve | Book review | 19 June 2025

Join us on Patreon

‘The quality that we call beauty… must always grow from the realities of life.’ So wrote Japanese novelist Jun’ichirō Tanizaki. The documentary genre embodies this and seldom are there photobooks to which I feel personally connected, but the ones that do resonate are related to my youth and the region of my hometown of Newcastle upon Tyne in the UK. Tish Murtha’s photographs of the working class districts of Elswick and Benwell, where I was born, are stark reminders of the streets where I played during the 1970s; I could have been one of those scruffy kids jumping out of the window of a derelict terraced house onto a precarious pile of mattresses. Photographs by Chris Killip of The Station (2020), an anarcho punk music venue across the Tyne River in Gateshead, a space I regularly frequented from the very first day it opened back in 1981, capture those spiky haired and familiar faces; a visual portal transporting me back to the frenetic energy and pungent odorous array of hairspray, soap, glue, and sweat. And now, Writing in the Sand from Dewi Lewis Publishing: a homage to the sandy beaches of the North East of England and the people who relaxed there, by Finnish documentary photographer Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen. Photographs of places so familiar to me, inciting a myriad of archived memories including the Spanish City, an amusement park located near the seafront of Whitley Bay that I regularly escaped to while ‘nicking off’ school, eating chips and playing Space Invaders with my mates.

In 1969, before finishing her film studies at Regents Street Polytechnic in London, Konttinen moved to Newcastle upon Tyne and co-founded the Amber Film and Photography Collective, a group of concerned documentarians focused on capturing working class communities and the effects of the rapidly disintegrating industries and the distinct social and cultural identity of the North East. They believed in long-term commitments towards communities spanning years, to integrate as much as possible to achieve an honest representation. Konttinen exemplified this dedication. That said, since it opened in 1977, the collective’s adjunct Side Gallery has always had a hard time keeping afloat. But now it really is sinking into oblivion; as of this time of writing it is ‘currently closed’. The gallery is no longer supported as a National Portfolio Organisation by Arts Council England, which is a disgrace and though the commitment and hard work ingrained in the photographs will forever remain, the momentum of the Side Gallery will halt and disappear just like the communities its photographers faithfully documented, just as the writing in the sand.

There is wonderful footage from 1974 of a young Konttinen featured on the then popular BBC current affairs programme, Nationwide. The reporter is full of praise for Konttinen’s “remarkable collection of photographs” taken of Byker and the tight knit community of working class people who lived there. These Victorian houses in back to back terraces were classified as slums and demolished to make way for a new modern Scandinavian inspired urban design that culminated into the unique one-and-a-half mile long social housing block called the Byker Wall. The reporter is somewhat bemused about this middle class ‘girl’ from Finland who chose to live in Byker and who feels the warmth of the local community, describing the residents as genuine, gentle and worried that the very distinct social unity and character would be lost with people living in atomised flats of the Byker Wall. Such was the level of empathy that Sirkka felt towards the North East of England as she remained stoically dedicated to documenting the region to this day, with a remarkable level of intimacy and affection for the Geordies and their plight in an ever changing socio-political-economic environment. In an interview she told me that the collective “brought us together and served us well is our common goals. Our egalitarian constitution, self-determination, editorial control, creative freedom, sharing of resources, lasting friendships… We moved to the industrial north-east with the aim of giving voice to working class and marginalised communities.” The photobook, Byker, was published in 1983, and ranks as a seminal and important project in the humanist mode of documentary photography in the UK, and certainly on a par with Bruce Davidson’s East 100th Street social documentation of the inhabitants of appallingly impoverished living conditions in Harlem during the 1960s.

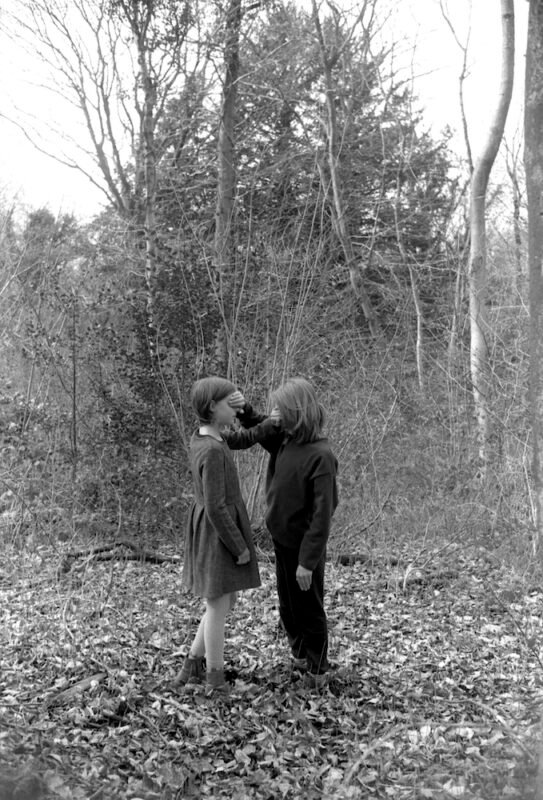

Writing in the Sand was originally published twenty-five years ago. The book features black and white photographs taken between 1973 and 1998 on the beaches at Cullercoats, Whitley Bay and Tynemouth – all in close proximity to each other. The beach is a concentrated space, a hive of human activity, and these photographs celebrate the eccentricities and odd juxtapositions of engagement. Most telling, especially photographs from the 70’s, and compared to today, is how the English working classes have an awkward relationship to the beach, wearing unsuitable attire for the environment; men smoking ‘tabs’ in their regular heavy twilled suits with trousers rolled up, cardigan wearing grandmothers, mothers and aunts allowing themselves the pleasure of feeling the grains of sand through their stockinged feet. A space to break free and let one’s hair down from the confines of the ‘hoose’ and drudgery of work. This is how it was. And somehow the beach equalises people, feral children turn upside down, metamorphose into mermaids and bury their dads with sand, lovers love and dogs go barking mad. In this uncluttered space people feel the sensuality of nature that allows the potential of unhindered free expression. The sea, sand and sky democratises an experience; the beach is a theatre of improvisation.

With humorous affection Konttinen’s observations embrace the energy and actions of quirky and intimate moments with absolute humility. Her distance is polite and her closeness is honest and balanced. This is photography of the humanist kind, and in skillful hands the emphasis is about the subject, not the photographer. With eloquence she captures the joy emanating from the gravitational pull to the sea, that place from which we crawled from the primordial soup. From time to time Konttinen punctuates the flow of pictures with quiet abstractions of sand, pebbles, seaweed and rocks, as if to accentuate the movement and perpetual cycle of nature, and put bizarre human presence into humbling perspective. Konttinen has a close affinity to these beaches. A few years ago we met at her local Tynemouth beach at King Edwards Bay where, with other women, she ritualistically swims, braving the north easterly weather even in the winter. She emerged fresh out of the sea and I photographed her portrait, wrapped in a terry towelling robe on that chilly morning before heading to the warmth of her home and a cup of tea.

The majority of working class people in the North East have endured a great deal of loss. By the 1970’s the industries of ship building, coal mining and steel manufacturing were virtually extinct and by the 1990’s had gone together with the communities it supported, and so began the onset of the grim reality of there being ‘no such thing as society’ anymore. Not to be sentimental about the good ole days of the working class as for sure it was always tough, but it seems the more we have the less we have; consumerism is an instant, addictive, gratification separating humans apart. Community, as Kottinnen prophesied in the Nationwide programme will be lost, and with it a sense of identity, dignity and bonding.

This is old school, classic documentary photography. Tony Ray-Jones, Homer Sykes, Martin Parr, to name but a few, spring to mind, all of whom focused on the peculiarities of the English at play. Konttinen’s project ended in 1998, and I wonder if such images could now be taken in our protectionist self-image controlled, hyper-ethical cultural environment. How refreshing to see the total absence of mobile phones and lack of homogenous, sweatshop clothing, though only a stone’s throw away as a common sight.♦

All images courtesy the artist and Dewi Lewis Publishing © Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen

—

Michael Grieve is a photographer, Director of ArtFotoMode, Hamburg Werkstatt Fotografie (HWF) and lecturer at Ostkreuzschule in Berlin. In 1997 he graduated from the MA Photographic Studies from the University of Westminster and then proceeded to work as a photojournalist and portrait photographer for publications internationally. He was Deputy Editor of 1000 Words and a writer for the British Journal of Photography. Since 2011 he has been Senior Lecturer at Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, Akademia Fotografie Warsaw and the University of Art and Design, Berlin, and currently teaches at Ostkreuzschule für Fotografie, Berlin. He is currently working on Procession, a project documenting the peripheral space between Athens and Elifsina, Greece.

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique and activism

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous Dahmani

• Shana Lopes reviews Agnieszka Sosnowska’s För

• Valentina Abenavoli discusses photobooks and community

• Michael Grieve considers Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler’s posthumous collaboration with their late family member

• Elisa Medde on Taysir Batniji’s images of glitched video calls from Gaza

Join us on Patreon today and be part of shaping the future of photographic discourse