They were already here

Donna Gottschalk and Carla Williams make their French debut in Le Bal’s latest exhibition, We Others, accompanied by an interpretive text by Hélène Giannecchini. Bringing together first-person narrative and a wide range of photographs spanning decades of work to tell stories, explore invisibility and consider intergenerational connections, it is the nuance and fragility that stand out; a quiet yet political manifesto about absent bodies, writes Eve Hill-Agnus.

Eve Hill-Agnus | Exhibition review | 16 Oct 2025

Join us on Patreon

Nous Autres (We Others), the exhibition currently at Le Bal in Paris, featuring the work of American photographers Donna Gottschalk and Carla Williams, with an interpretive and curatorial text by art historian and writer Hélène Giannecchini, is a photo-literary space that interrogates lacunae and reimagines how we enter a text, an image, an exhibition.

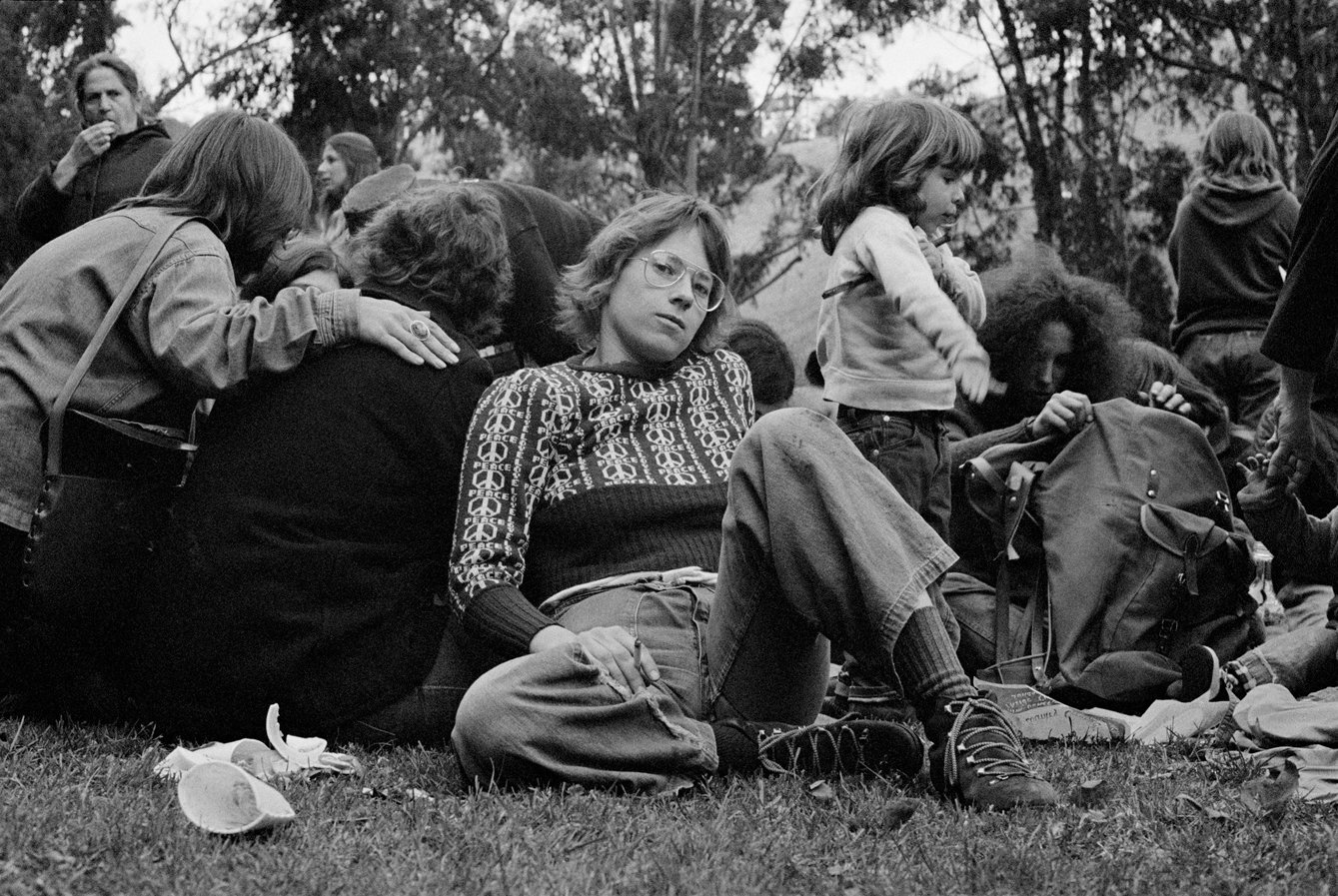

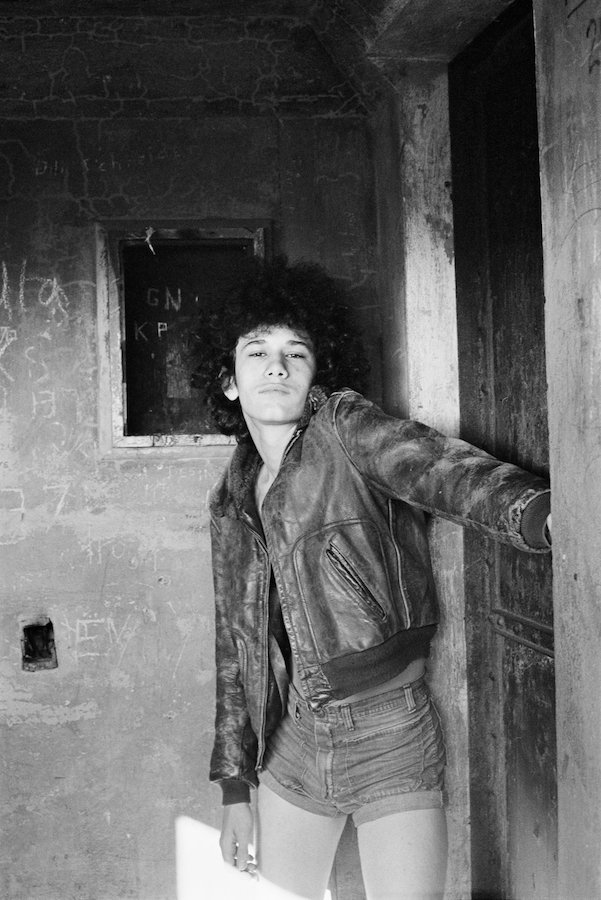

Immediately, the images draw you in, as into a world of people you know or might hazily remember through one degree of removal, friends of friends: for example, the brick building and the water gathering along naked branches in the first photograph, titled ‘Oak,’ which is the name of the woman whose distant gaze seems plunged in reverie. I want to know what time of year the image was taken and what is behind her private trance, the semi-blur of her Mona Lisa smile. ‘Alphabet City, New York, 1969,’ the caption reads. Next to it: the casualness of a quartet of friends, cigarettes in hand. Here, ours is a plunging view, as though interrupting their conversation. ‘Chris, Oak, Binky and I, Baby Dykes—E. 9th Street, New York, 1969’ Donna Gottschalk’s chosen label tells us in what scans as shorthand.

It is a snatched moment of life, like the image of her in bed with a lover. In that tender moment, the self-consciousness of the self-portrait means they are aware of being seen, but by an insider, and the camera’s soft focus feels like a signifier of comfort, familiarity, affection.

The biographical/autobiographical element pulls the viewer into the story: Gottschalk’s anchoring in Manhattan’s Alphabet City, where her mother had a beauty salon and the portraits of neighbours, friends and lovers were the terrain of her first studies with the camera she bought in 1968, against a backdrop of suppression and the double violence of homophobia and poverty.

Hélène Giannecchini’s wall “essay” that accompanies and frames the images introduces the characters in a manner reminiscent of a work of fiction; she reactivates the archive and reinstates it in a narrative that fills in gaps with first-person subjectivity. Because We Others is, in part, about the possibilities of such a deliberately subjective narrative stance – its potential, counter-intuitively, to involve the viewer in greater levels of transparency, intimacy and, ultimately, truth. Such a stance aims to dissolve the boundaries between us and the images, us and the people in them.

“They are barely 20 years old and stare defiantly into the camera; up on the rooftops with cigarettes in their hands, propped against brick chimneys, or standing on the fire escape platform that runs the length of the facade…” the wall narrative begins.

With one sentence, intimacy becomes an atmosphere, the point of view into which I enter with an insider view that makes the temporal stakes palpable. More than a curator or theorist, Giannecchini is writer-participant, writing the narrative space between the images.

What emerges is the construction of a ‘we,’ a delicate, subtle, ambiguous but powerful synergy. We Others asks: Can we attempt to counter a misleading or reductive discourse centred on a monopoly of truth by unapologetically claiming and situating our point of view? “I don’t say what Donna is,” Giannecchini points out, “I speak about the Donna I meet.” This is an ‘other’ way of doing curatorship, of doing a show.

Part of the exhibition’s thrill is the unlikely and fortuitous way it came together. This is a story of female friendships and chance. Giannecchini arrived late one night at Gottschalk’s farm in Vermont, having heard about her work through a gallerist friend. “What’s amazing is that Donna very quickly trusted me,” Giannecchini told me over the phone. “And the fact that I returned. I told her, ‘I will be back,’” she recalls. “And I was back within the year.”

That Gottschalk entrusted Giannecchini with the negatives she had slowly been printing in spare moments of time over the past half century could be reminiscent of the passing of a baton, though the energy feels more womb than baton. The powerful subtleties of trust are cross-generational and co-generating.

Williams, who also kept her pioneering work to herself for years, is part of the trio of generational co-creational narrative hybridity. A friend of Giannecchini’s proposed a lunch in New York between the two. Unbeknownst to Williams herself, she had been living with Gottschalk for decades: a photocopied image from a book of a young woman holding a sign from a march (“I’m your worst fear, I’m your best fantasy”) was Gottschalk, young and radical.

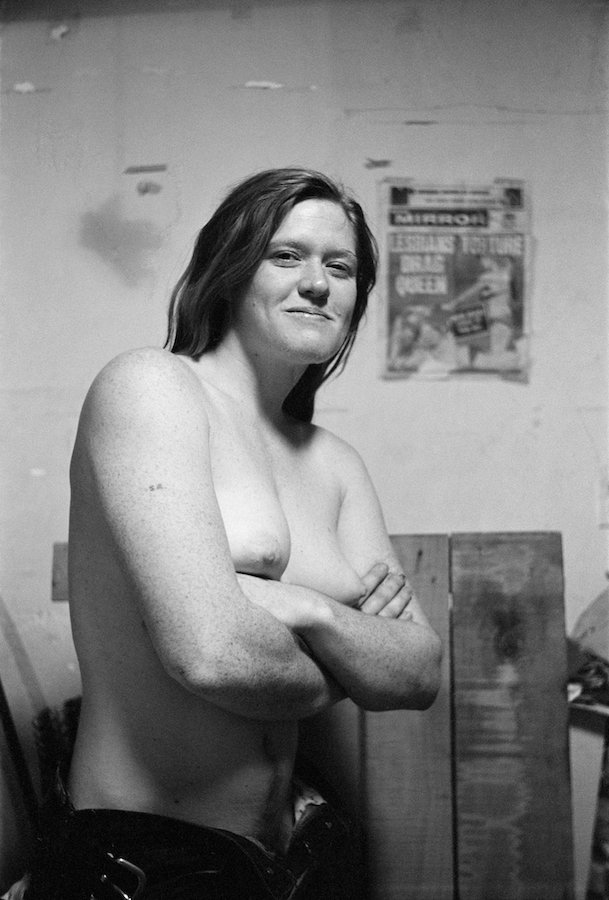

They may live a similarly marginalised experience, but Gottschalk primarily turned her camera toward others while Williams turned it toward herself, two opposing solutions to carving out a visual history via bodies.

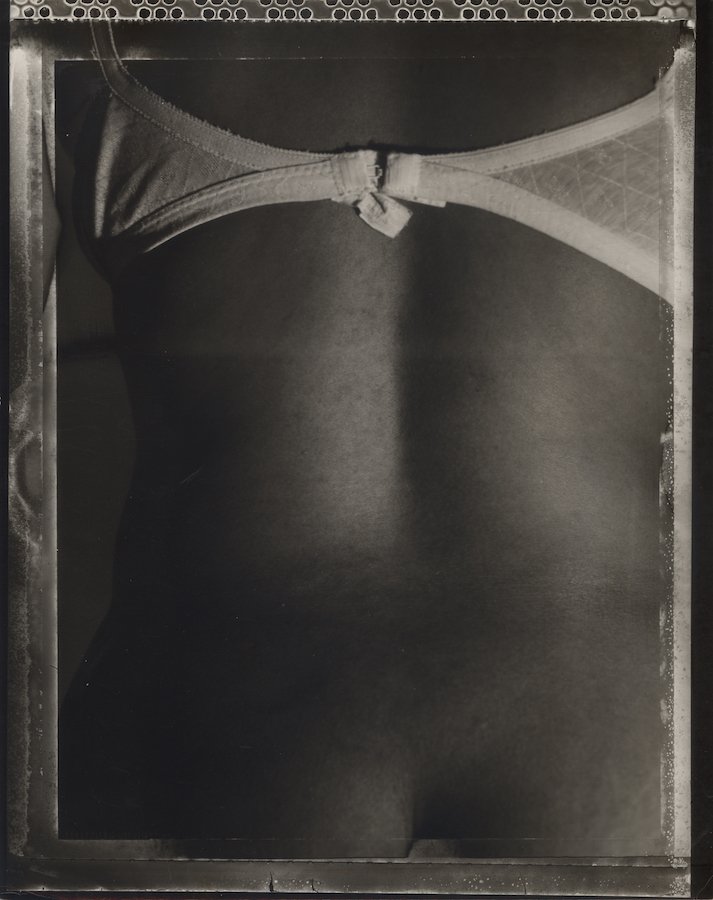

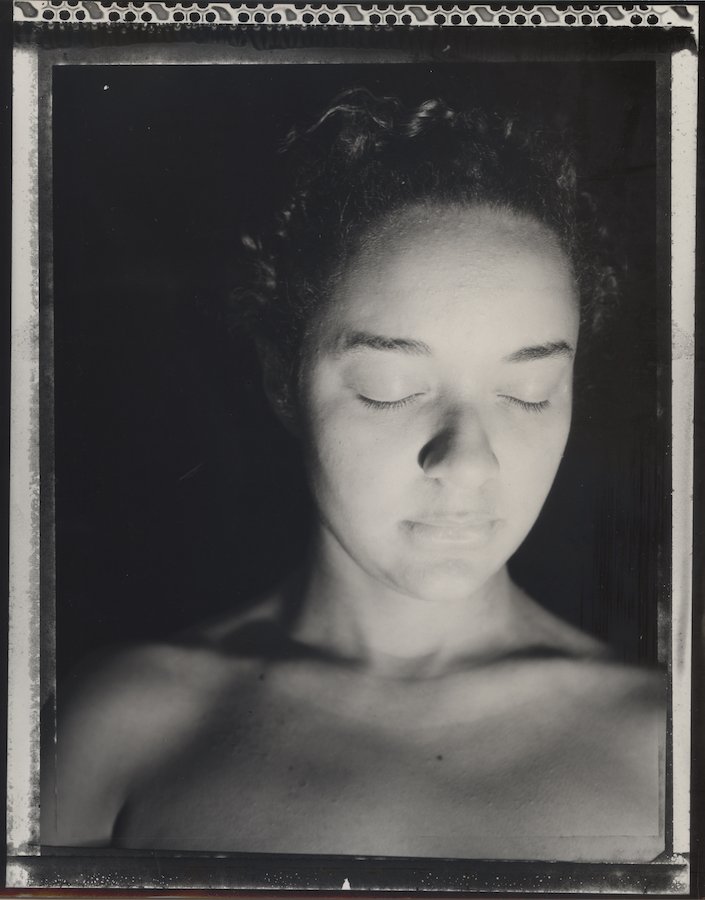

The work in Williams’ series Tender, the majority of which she made while an undergraduate student in the 80s, makes self-portraiture an intimate act of visibility and resistance. She is among both the ‘we’ and those who placed the quotation marks around ‘others.’ The way we change the history of photography is by questioning how we tell stories and whose stories we tell.

Part of the way the show traces other ground is in its inquiry into the intersections of class and identity. In Gottschalk’s photographs of Alphabet City from the late 60s and 70s, this place where broken windows signal the before and after of human life, words say something subtle about how we can hold bodies. I cannot help but notice the linguistic clues in the signs: “Ask about our lay-away plan” a flooring store window entices and “Senior Citizens Everyday Special” announces Alfred’s Beauty Salon, where a man, resting his hand on the back of a chair, looks at the camera. What they suggest is community, belonging. And the fragility of people helping each other through small gestures. Even the apostrophe in a shop name like “Johnny’s” suddenly strikes me as an intimate and therefore tentative form of claiming.

‘Chickie in my mother’s beauty parlor,’ is the title of Gottschalk’s portrait of her short-haired friend in bellbottoms amid the older women in her mother’s salon. It shows how much class and identity are integrated in her world. What she shows us are working-class queer folk. Embodiment and participation are enmeshed, ultimately. Extraordinarily deep empathy arises for those bodies that are so often invisible. That fragility is in Gottschalk’s work and life, a sort of invisibility held at bay. And yet one senses that she and Williams are part of a community of reciprocity and care, and of ferocity beyond words. Something holds their worlds together. Maybe it’s us. What if it were?♦

Donna Gottschalk images courtesy the artist and Marcelle Alix © Donna Gottschalk / Carla Williams images courtesy the artist and Higher Pictures © Carla Williams

Nous Autres (We Others) runs at Le Bal, Paris, until 16 November 2025.

–

Eve Hill-Agnus is a Franco-American writer, editor and translator based in Paris. Her art writing has been published in Artforum, Frieze, ARTNews, Patron, and other outlets. Her literary translation of Mariette Navarro’s novel Ultramarine (Deep Vellum, 2025) was awarded the Albertine Translation Prize.

Images:

1-Donna Gottschalk, Jill, President Street, Brooklyn, New York, 1968

2-Donna Gottschalk, Oak, Robin, Binky, Chris and I, Baby Dykes, E. 9th Street, New York, 1969

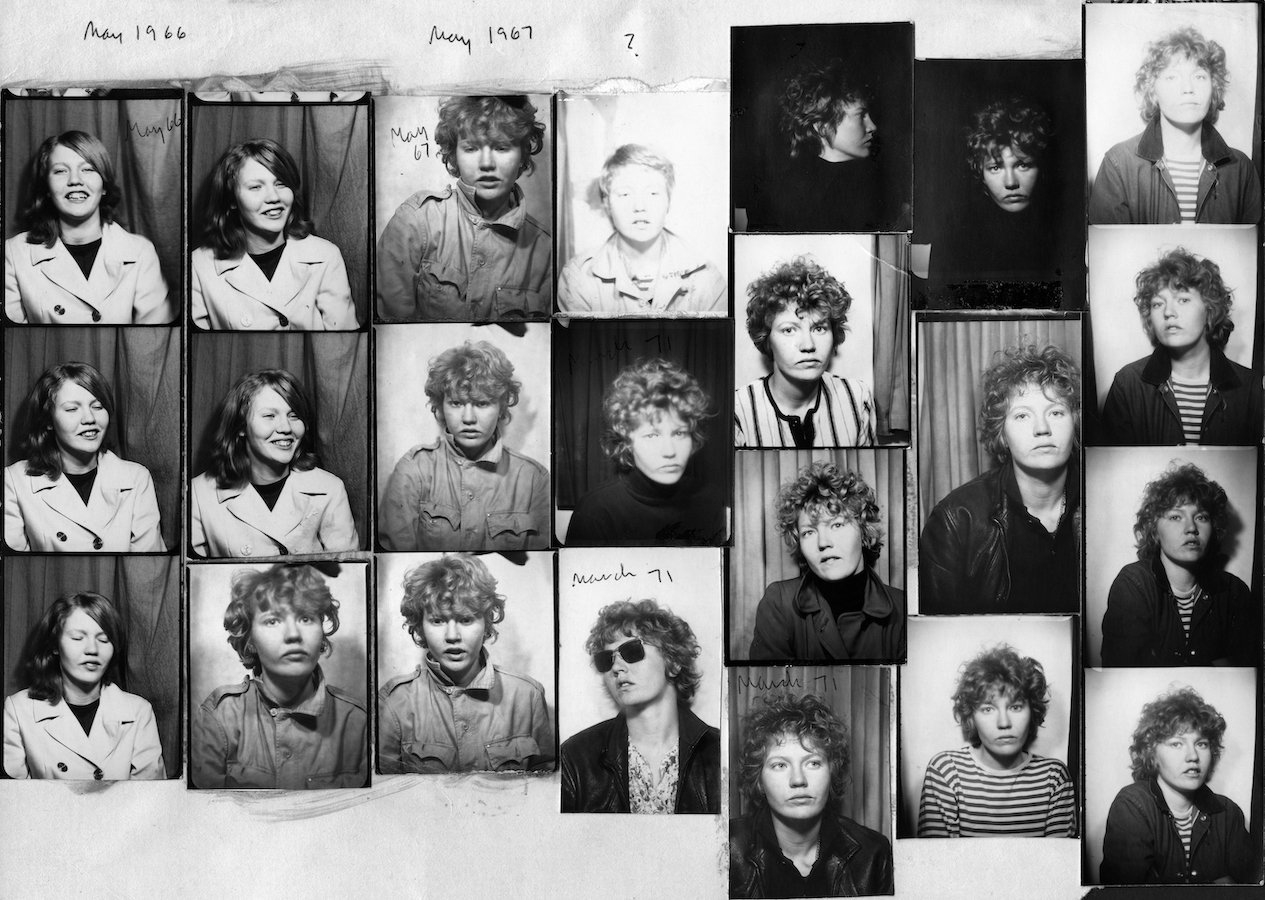

3-Donna Gottschalk, Photobooth portraits, 1966–71

4-Donna Gottschalk, Marlene, E. 9th Street, New York, 1968

5-Donna Gottschalk, Chris in a taxi, New York, 1970

6-Donna Gottschalk, Chris in a taxi, New York, 1970

7-Donna Gottschalk, Marlene and Lynn, E. 9th Street, New York, 1970

8-Donna Gottschalk, Self-portrait with JEB, E. 9th Street, New York, 1970

9-Donna Gottschalk, Self-portrait during a GLF meeting, E. 9th Street, New York, 1970

10-Donna Gottschalk, Lesbians Unite, Revolutionary Women’s Conference, Limerick, Pennsylvania, October 1970

11-Donna Gottschalk, Jill, San Francisco, 1971

12-Donna Gottschalk, San Francisco, June 1972

13-Donna Gottschalk, Myla, Sausalito, California, 1972-73

14-Donna Gottschalk, Myla, 16 years old, Mission District, San Francisco, 1972

15-Carla Williams, Untitled (bra), 1987-89 (Albuquerque)

16-Carla Williams, Untitled (face in light), 1990 (Albuquerque)

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique and activism

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous Dahmani

• Shana Lopes reviews Agnieszka Sosnowska’s För

• Valentina Abenavoli discusses photobooks and community

• Michael Grieve considers Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler’s posthumous collaboration with their late family member

• Elisa Medde on Taysir Batniji’s images of glitched video calls from Gaza

Join us on Patreon today and be part of shaping the future of photographic discourse