Photobook Conversations #4 | Valentina Abenavoli: “Books have always been the proof of lives lived”

Photobook Conversations is edited by Ana Casas Broda (Hydra + Fotografía), Anshika Varma (Offset Projects) and Duncan Wooldridge (Manchester Metropolitan University). Sitting alongside the earlier Writer Conversations (1000 Words, 2023), edited by Lucy Soutter and Duncan Wooldridge, and Curator Conversations (1000 Words, 2021), edited by Tim Clark, it completes the series exploring the ways our understanding and experience of photography is mediated through exhibitions, writing and publishing.

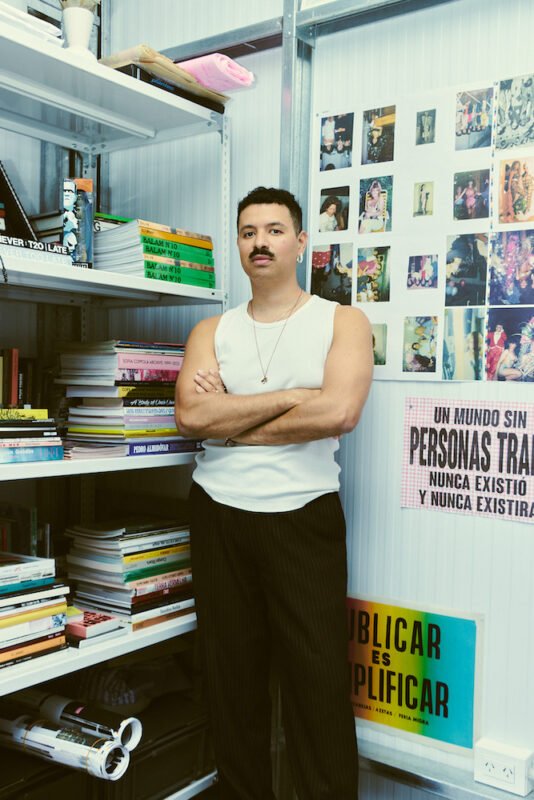

Valentina Abenavoli | Photobook Conversations #4 | 19 Dec 2024

Valentina Abenavoli is an editor, book designer and visual artist working at the intersection of photography, video, sound and text. She has led intensive workshops on photo editing and bookmaking internationally. In 2012, she co-founded Akina, an independent publishing house producing challenging photobooks by emerging photographers. Her first photobook, Anaesthesia, was released in 2016, followed by her second book, The Harvest, in 2017. Both are part of an ongoing trilogy investigating the subjects of empathy and evil. Recently, she co-founded Neighbour, an alternative art space in Trivandrum, India, focusing on exhibitions, publishing and collaborations.

What were the encounters which started your relationship with photobooks?

When it comes to books, there’s neither a clear beginning nor an end. It’s an ongoing, evolving relationship. It wasn’t a sudden spark or love at first sight. Rather, it grew slowly, rooted in childhood, in stories, in diaries filled to the margins, in old family albums like entire encyclopaedias of strangers. Something deeper stirred within me, drawing my mind toward far-off places and revealing the beauty in life’s most ordinary details – all recorded and preserved in printed form. Books have always been the proof of lives lived. They offer a suspended moment in time, a refuge from reality, an open invitation to step into an extraordinary “other” world.

When I think of my life before working at Akina, I recall a fascination for photobooks that was raw and unshaped – an early, unrefined intuition that supported an imaginative approach without prior knowledge, in its mad and vast simplicity. I would pick up a book because of its cover or title, without knowing what to expect with each turning page. As I learned the narrative structures and rhythm of sequences, I took my sweet time with each book, and some stories, in all their complexities, would linger in my mind for a long time, unfolding in multiple serendipities and nocturnal epiphanies. It was a real pull, a magnetic one, that had been the primary subject of my thoughts for many years. That blissful ignorance is what I now miss deeply.

Many years ago, while still studying, I worked at a book fair in Torino, Italy, in a rather simple role. I was responsible for handing out microphones to writers and publishers as they took the stage. In between talks, I would slip away to wander the stalls with Federico Clavarino, who, years later, would become one of the artists Akina collaborated with. Together, we flipped through the works of Italian photographers like Letizia Battaglia, Luigi Ghirri and Mimmo Jodice. At times, we kept an eye on the clock to avoid missing the next talk, but then one of us would inevitably get lost in the spell of books – the weight, the texture, the world of a stranger offered to you as the most intimate shared space. These books were far too expensive for me, so I filched a few. It’s a good story to mark the beginning of my relationship with photobooks. There was a desire to understand the realm of these visual storytellers, using the book form to express and communicate something invaluable – an expensive magic.

In the same city, around the same time, I would often spend hours among the dust-coated wooden shelves of La Bussola, a local bookstore selling old, preloved and out-of-print titles. These books waited for someone – anyone – to come along and rescue them from the anonymity to which they were relegated. Sometimes, I think many survived years under the indifferent dust of the bookshop only to gather a new layer of dust on someone’s shelf at home. The gesture of taking a forgotten, preloved book that could be reintroduced to someone’s life, where it might one day be opened again, its pages turned by another’s hands. There was a kind of timelessness to it, a quiet, slow resistance to finitude, defying the rules of a fast-paced market, where books need to be sold out within the same year of release. The photobook selection was scarce and mostly generic, but some obscure gems I still own today were found there, on a corner shelf labelled ‘fotografia’.

When this fascination for photobooks found me, beyond the coffee table books of famous photographers whose names I never learned, there was a growing urge for independence in photography – a push against the establishment, a need to create something outside the mainstream. From the underground up. I see now the sense of rebellion that led me to want to be part of that movement of zine makers and cheaply produced books filled with loud content and honest rawness. I started collaborating with a literary agency, learning editing, publishing and marketing. But I think it wasn’t enough to simply work with books. I wanted to create the book object itself, from scratch: the design, the choice of size, paper, sequence and text. A book is more than just a collection of images or words – it has the intrinsic quality of being made by many hands, collectively contributing to different stages of creation, production and dissemination. I wanted to be part of that effort to create vessels of beauty and change.

It is an everlasting joy and a never-ending pain, my relationship with photobooks. It has its roots in intuition and surely changed my life when it began, but I haven’t yet figured out how much I’ve changed in relation to them. It used to be all I could talk about – books, books, books – and I still do, even though Akina no longer publishes, and I no longer stand on stages, advocating for space and support to experiment with new ways of expanding the market beyond its bubble. I’m just quieter and more specific about it now, which seems to go well with age.

What is your process for arriving at decisions about books and the projects that you undertake?

As a publisher, I was once drawn to photographic projects that required courage, often tackling controversial or thought-provoking subjects. I was keen to engage with works that had the potential to spark conversations, provoke complex social dialogue, or explore political and existential themes. If the visual narrative was compelling enough, I believed that words weren’t necessary in the book. But both the market and I have changed since then. What excites me most today are projects that embrace interdisciplinary approaches, where photography is one part of a larger composition – often working alongside text, illustrations or video stills. In this context, the book itself becomes a form that embodies connections between disparate elements. Each spread follows the next, creating both linear and non-linear relationships between subjects, objects, actions, places and time. These parallel narratives, and the potential meanings they carry, are familiar to us and can be part of a larger scope, like a symbiotic root-like system of interconnections.

The concept of the “third image” created by the juxtaposition of two images placed side-by-side is that inexplicable mental image that words cannot express, yet it’s something we all understand and discuss when reading, teaching or analysing photobooks. Being by contrast or by accumulation, this is a catalyst for endless possibilities and effects. It reflects a state of being mutually dependent, not only in the natural world but across different disciplines as well. It speaks to the emotions we give and receive, the long-term use of knowledge, and the process of unlearning in order to learn again. It really highlights humanity’s complex relationship with both the known and the unknown. And in this sense, the more we look at the world in an interrelated way, the more we can deepen our sensitivity to various subjects and towards each other.

There is a clear need to bridge the gap between art practices and academic research, as both fields can benefit from each other’s insights. We are too accustomed to thinking, working and acting within the photography niche, but by doing so, we often tend to congratulate each other’s results without truly challenging the way photography can serve as a carrier of meaning. If we are curious about humanity, we would only benefit from collaboration, which allows us to better contextualise knowledge beyond specific areas of study.

We often formulate projects based on our imagination and speculation, and I am deeply fascinated by this potential, by the process itself. I like to linger in the urgency of ideas that provoke thought with no immediate purpose other than offering alternative perspectives. I like the aftermath of creation, when the work becomes at the service of an audience to be dissected, interpreted, carried forward in any iteration possible.

Over the years, I’ve come to realise that a new model of the art world is needed, one that challenges the individualist culture of authorship and creative production. I prefer to engage in works that are rooted in collective experience and that are participatory. This is where my interest in collaborative authorship began – where books and exhibitions are the result of dialogues, negotiations and exchange, and where there’s a certain acknowledgement of the new forms projects have taken, emerging from a shared creative responsibility of multiple voices. Artists, writers, designers, curators and editors add layers of meaning, context and interpretation of the work, making it a complex and dynamic entity beyond the purely artistic expression. It is within this space of mutual influence, where roles and responsibilities intersect, where I find the greatest creative potential to break down the hierarchies in the art world and maybe create a more sustainable model for all.

I think moving to Kerala, India, and working primarily with artists and institutions from the Global South for the past five years, has given me a different perspective on what collective narratives can achieve. This shift from the individual to the collective requires rethinking agency itself, recognising that personal stories are always entangled with larger social, political and economic forces. It means moving beyond isolated experiences to examine the structures that shape them. There’s a need to decolonise our understanding of stories and power, and I believe this will always shape my collaborations moving forward.

How do you like to work with people?

Meaningful conversations are the foundation of how I work with artists. I believe that truly listening to someone’s story is essential in my role as both editor and designer. I like to be convinced, questioned and challenged. Serving the potential of the work, bringing forth everything that is yet to be said or seen. This requires not just a deep understanding but also a healthy mix of empathy, respect and imagination to translate these works into book form.

Trust is built by being open to each other’s vulnerabilities. There was a time when conversations with artists were so visceral and emotional that hours would pass without eating or sleeping, leaving my mind on fire. I’ve only recently learned the importance of saying “no” and setting boundaries. I experienced complete burnout once, and it took me two years of healing and rest to be able to absorb what an artist wanted to share and to help them navigate the book form again.

Now, I’m much more selective about the projects I take on. Becoming a mother gave me a new perspective. The urgency I once felt to engage with every intriguing project has shifted. Now, I weigh not only the potential impact of a project but also how it aligns with my current priorities – mental health being one of them. There’s still a bounce of ideas and shared vulnerabilities, but it’s a slower, more considered process.

How do you balance choices between working with highly specific materials or processes, and the desire for access?

My practice began with a clear focus on balancing specific materials and processes with accessibility. In 2012, we at Akina started printing and binding handmade books at home, inspired by zine culture as a revolutionary, accessible way to spread ideas. Without funds for offset printing, we explored new approaches to both content and form, collaborating with emerging photographers. We managed to get trial machines twice, and published four zines and two books in editions of 100 to 200 copies each, paying only for the paper. London, at the time, was alive with creativity, and we had the support and courage to leave stable jobs for counterculture.

Over the years, we produced handmade books in two editions – a standard and a collectible edition – at prices people could afford (£8 to £12 for the standard edition, £35 to £50 for the collectible). All the books sold out within a very short time, leaving us often with a backlog of production and long nights spent surrounded by obscure vinyl records, managing humidity in perpetually damp London and stacks of paper covering every inch of our space.

The idea was to meet the needs of both collectors and those who wanted to be part of the community but couldn’t usually afford expensive books. It was our way of addressing the divide we saw in the photobook market, where books either became collectible and expensive or were inaccessible to many artists and readers. It was also the proof that limitations – being money or materials – can really help creativity to strive, instead of containing it.

Large companies reach broader audiences with offset printing, lowering costs and benefiting from wide distribution while producing high-quality books. However, I never worked with distributors, and staying independent and sustainable was challenging. Eventually, we decided to shift to offset printing as demand grew, but in doing so, the books seemed to lose their intrinsic value of being unique. That was when it stopped being fun and transformed into something more rigid – a business governed by profitability frameworks. Although I partnered with a visionary printer in Istanbul, Ufuk Sahin, known for his ability to challenge the impossible, creativity can become subject to the pressure of meeting market demands. This leaves less room for failure when the investment is too high. I don’t have the answers. Ultimately, I closed my publishing house after eight years and many books produced.

What do you think is the significance of the shift towards the book as an object?

It’s the tactile experience, the quiet moment of slowly unfolding someone else’s work in a sentimental manner. In a world that’s increasingly digital and ephemeral, the book is an anchor, a testament, an act of resistance. When one begins to notice how a book feels, and makes a ritual out of it – picking it up, running the fingers over the cover, that first crack of the spine, the smell of the ink on the paper, the whole experience of reading becomes an encounter with its own physicality. It slows you down, draws you into its pace, and invites you to stay for a while. The book becomes a place, almost, one that you inhabit for a time. And what a profound, enduring form of communication it becomes – tangible, intimate and moving – capable of being disseminated while resisting the passage of time.

Anaesthesia, the work I am most attached to, asked to be a book from the very beginning. It emerged from a profound personal struggle, fuelled by anger at the Western bias of empathy towards the Middle East – a bias that has perpetuated the dehumanisation of certain populations, shaping cultural narratives and influencing perceptions for decades. The choice to work on a book – densely black in its form – was the most visceral reaction to a world of violence and indifference. In exploring how reality is documented, shaped and presented to us, the book poses a fundamental question: if we’ve been overwhelmed by images of horror and war, becoming numb to the suffering of others, how will we choose to respond? Through the way the images and words are placed in the book, I wanted to invite others to feel, to pay attention, and to have radical positions towards humanity. Now, one year into the ongoing genocide in Palestine, on the verge of a much larger escalation, we are still bearing witness to our collective history, we are still challenging the false narratives. That book is a small testimony.

What is the place of language and writing in a book of photographs?

I’ve always loved the freedom that lingers at the edges of the image, outside of the frame. It is where the reader is really able to imagine. When words are offered, language becomes at once illuminating and restraining. The writing evokes what is not immediately visible. It guides, suggests, hints and eventually offers a way to begin, without ever telling you how to end. But also, words can impose. They can point to specific narratives, excluding, in part, the infinite possibilities of imagination. On the other hand, words that are not descriptive, and that generate abstract meanings, can create a beautiful tension, where text and image subvert each other’s autonomy, pulling in opposite directions – one towards specificity, the other toward openness.

An intellectual controversy that has accompanied photography since the beginning is whether it can be defined as a form of language. I’ve often thought it is reductive to classify it this way, and I believe its unreliability as a form of language is one of the reasons why contemporary photography often relies on archetypal symbols, such as an isolated house in a bare landscape or hands holding something (or each other). These are simplistic, symbolic representations used to convey meanings of relationships, of belonging, of loss or identity, but they are not arranged in a systematic structure, which leaves them open to a certain simple interpretation without offering the precision of language. Many might disagree and argue that this approach opens up the ambiguity of photography for viewers who lack visual literacy. Words allow for precise and systematic communication, yet they also leave room for ambiguity due to the absence of a precise visual representation. On the other hand, when images are overly symbolic, they offer a clear visual representation but lose the ambiguity inherent to the photographic medium. I am looking at that isolated house, and I cannot imagine another type of house, which, in itself, reduces the interpretative imagination.

I believe the only way to resolve this dilemma – and to elevate the photobook market to the same level of prominence as written books – is to make visual literacy a common subject, continuously and at every age, in every educational institution. To be more mindful about the current world as it is represented in images. Because art asks for a dual engagement: a visual one and an intellectual one. And too often it leaves out those less familiar with the other “language”.

Who have been the models or templates for your own activities?

In many parts of my life, I can trace exactly where it all began – the contexts in which I gathered each facet of the person I’ve become, the moments when decisions were made, who stood by me, and who drifted away. It’s like a vivid map made of memory lanes and sentimental journeys, and I cherish every turning point, each past version of myself. There is a series of consequential events, and connected people, that have led me here, now, in Trivandrum, with my partner Joe and our son Eli.

It was 2015 when I met Sohrab Hura in Arles for the first time. He is not only an incredibly talented and considerate artist but also a reliable friend who has this unique ability to connect like-minded people. With a short and precise email, he introduced me to the wonders of Nayantara Gurung Kakshapati, the founding director of photo.circle, Photo Kathmandu and Nepal Picture Library. It took a year and a half before I could finally meet her in Kathmandu, and we spent a full week in one of the most immersive and life-changing workshops I’ve ever run. I have pictures of the students editing at 4am, with book cover cloths wrapped around our heads like veils. After that week, we began calling each other “mama”. I believe it was love from the start, but also the joy of finding that our complementary skills allowed us to create something powerful together.

Nayantara’s work is about the transformative power of visual storytelling – not just as art but as a force for social change. Together, with a growing team who feel more like family to each other and to me, she’s shown how photography and visual media can empower communities to reclaim their own stories. These aren’t just acts of creativity, but acts of rebellion against dominant narratives. What makes their approach special is that it’s about building systems that nurture relationships and spark long-lasting dialogue. It challenges the status quo, drawing from indigenous knowledge to reframe ideas of inclusivity and equity, using art, ecology and political stands as collective tools for change.

In 2018, during my artist residency for Photo Kathmandu, I stayed at a guesthouse in Durbar Square in Patan. Every morning, the temple bells would wake me at 5:30am, and from my window, I’d watch people of all ages and backgrounds interacting with the exhibition The Public Life of Women. It was surreal – people staring, reading, commenting on archival images of women who made history, all before dawn. It’s unimaginable to have such public engagement in the West at that hour, let alone one that addresses themes of gender and society. It made me question who we create art for and why.

I find myself thinking often about the present – about what role I have in our community, and how deeply Nayantara and the photo.circle family have inspired me. My mind drifts to Neighbour, the space Joe and I are about to open here in Trivandrum. It feels like the necessary next step, an extension of everything I’ve learned and believed in as an artist, a publisher, a designer, an educator and as a witness to current times. Neighbour is the combination of books, art and coffee, basically what makes my everyday. It is a reflection of our hope to engage with the world through the act of gathering, of being present with one another. I hope we can become a catalyst for change – however small that might be at first in our neighbourhood – where conversations can have that imaginative narrative, and books and art can push boundaries, challenge perceptions and ask difficult questions.♦

Further interviews in the Photobook Conversations series can be read here

Images:

1-Valentina Abenavoli © Joe Paul Cyriac

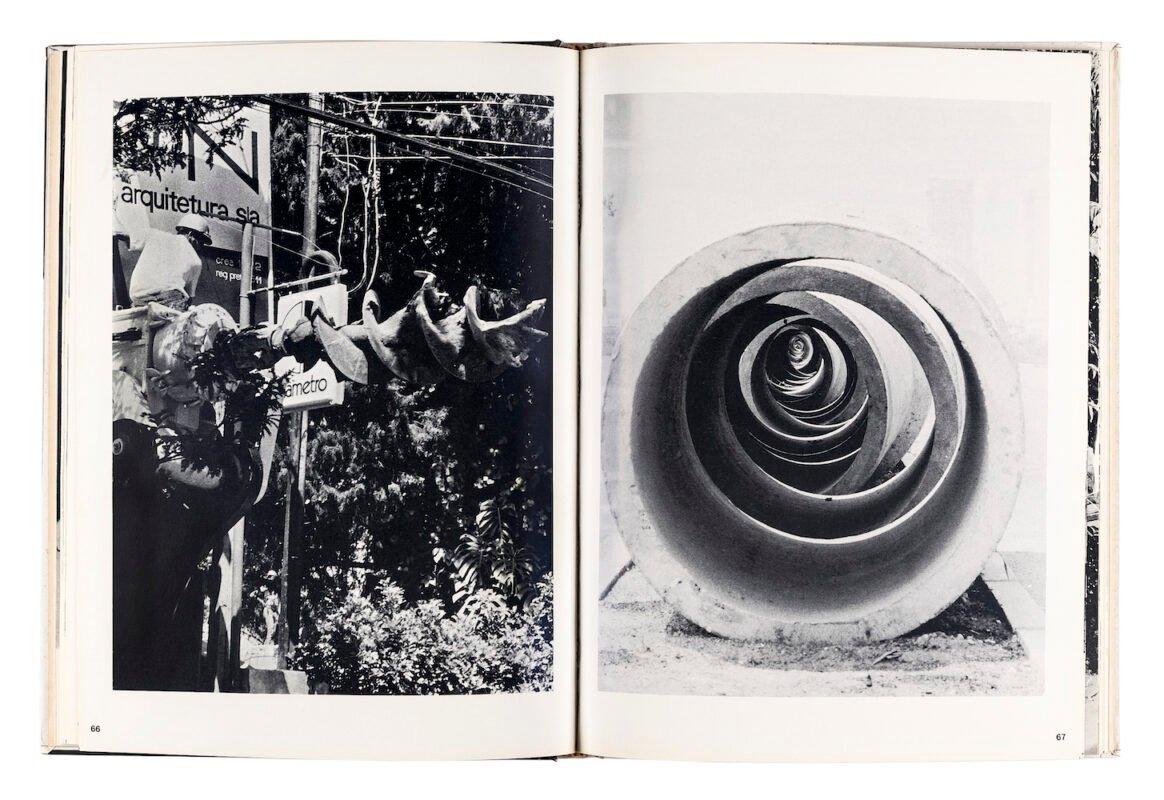

2-Yusuf Sevincli, Oculus (Galerist and Galerie des Filles du Calvaire, 2018)

3-The Public Life of Women: A Feminist Memory Project (Nepal Picture Library, 2023)

4-Sayed Asif Mahmud, Marta Colburn and Jessica Olney, Bittersweet, A Story of Food and Yemen (Medina Publishing, 2024)

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique and activism

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous Dahmani

• Shana Lopes reviews Agnieszka Sosnowska’s För

• Valentina Abenavoli discusses photobooks and community

• Michael Grieve considers Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler’s posthumous collaboration with their late family member

• Elisa Medde on Taysir Batniji’s images of glitched video calls from Gaza