Top 10 (+1)

Photobooks of 2024

Selected by Tim Clark and Thomas King

As the year draws to a close, an annual tribute to some of the exceptional photobook releases from 2024 – selected by Editor in Chief, Tim Clark, with words from Editorial Assistant, Thomas King.

Tim Clark and Thomas King | Top 10 photobooks of 2024 | 05 Dec 2024 | In association with MPB

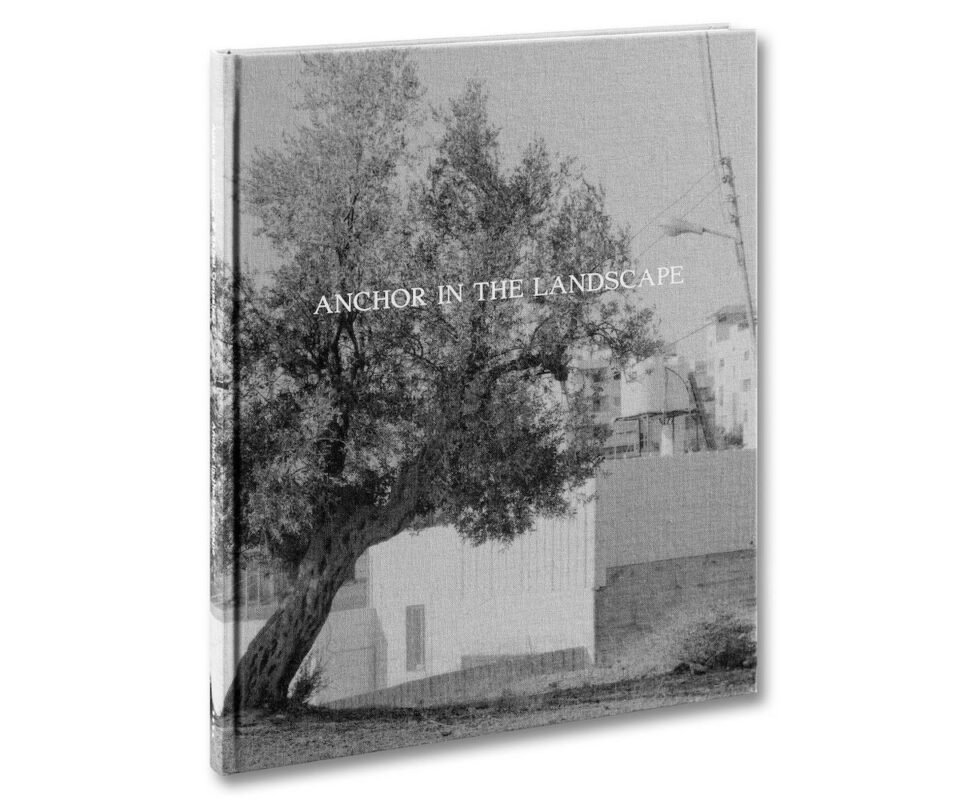

1. Adam Broomberg & Rafael Gonzalez, Anchor in the Landscape

MACK

Studied witnesses to the State of Israel’s attempt to erase a people and their history, Adam Broomberg and Rafael Gonzalez present a quiet yet forceful declaration of Palestinian resilience in Anchor in the Landscape. This striking series of 8×10 black-and-white photographs of olive trees, accompanied by a text from legal scholar and ethnographer Dr. Irus Braverman, made a bold statement at the 60th La Biennale di Venezia earlier this year. Each page of the book pairs a photograph with its precise geographical coordinates, where the olive tree – facing destruction and theft by settlers – anchors livelihoods, culture, and presence in a relentlessly seized and ravaged landscape. The result is a haunting yet beautiful rekindling of connection to Palestinian land in the occupied territories.

2. Karolina Spolniewski, Hotel of Eternal Light

BLOW UP Press

Winner of the 2022 BUP Book Award, Spolniewski’s seven-year multimedia project-turned-book – replete with holographic foil cover – details the psychological and physical scars of detention, drawing on Hannah Arendt’s writings on totalitarianism and isolation. At its heart is Hohenschönhausen, the notorious Stasi prison in East Berlin, dubbed the “Hotel of Eternal Light,” where unrelenting artificial lighting twisted inmates’ sense of time. Documentary photography, scans of physical traces, inmates’ belongings, portraits, X-rays, archival imagery, and fragments of memories from conversations with former prisoners are combined through the book’s design approach to enhance meaning, one that also speaks through the inmates: one page repeats ‘everlasting interrogations,’ while another chillingly declares, ‘Every three minutes you get… blinded by the lights.’

3. Agnieszka Sosnowska, För

Trespasser

Agnieszka Sosnowska’s debut monograph, För (meaning journey in Icelandic), takes readers on a raw, poetic journey through the artist’s life on a beautiful stretch of unmistable wilderness. Originally from Poland, she immigrated to the United States as a child, then as a young adult spontaneously visited Iceland, met her partner and built a life there. Where nature is both a solace and an ever-present force, Sosnowska’s photography – especially self-portraiture – charts the ongoing journey of self-discovery and belonging. Against the pulse of land and community, her images invite a deeper reading, culminating in a confident yet vulnerable self-portrait of the artist. But to what end? Sosnowska doesn’t just capture her subjects and surroundings; as SFMOMA’s Assistant Curator of Photography Shana Lopes recently writes in her review, Sosnowska invites us to reconsider how labour, heartbreak, death, landscape, and the quotidian shape our idea of home.

4. Carmen Winant, The Last Safe Abortion

Self Publish, Be Happy

Since the re-election of the man who played a key role in overturning Roe v. Wade, Carmen Winant’s sobering photo album-style work – winner of the Author Book Award at the 2024 Les Rencontres d’Arles Book Awards – feels more urgent than ever. Published by SPBH Editions and MACK and designed with a bold spiral binding, Winant’s contemplative exploration of care resists the relentless efforts of anti-abortion movements and the far right to control women’s bodies. Featuring images of health clinics, Planned Parenthood locations, and abortion clinic staff whose tireless commitment sustains this fight, the book spans 50 years – from 1973, when abortion rights were federally protected, to 2022, following their dissolution. Winant reframes the struggle for care and autonomy as a testament to courage, resistance, and hope – urgently needed qualities. Read Gem Fletcher’s review here.

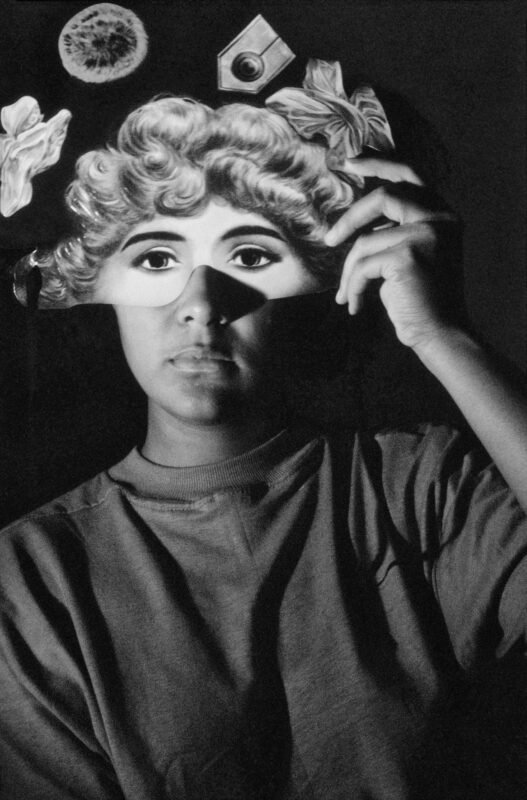

5. Carla Williams, Tender

TBW Books

It’s often a posthumous exercise to uncover a hidden trove of photographs, but for Carla Williams, her artistic debut has thankfully arrived during her lifetime—adding a new chapter to her distinguished career as a photo historian. At 18, while studying photography at Princeton, Williams began creating black-and-white and colour portraits using Polaroid 35mm and 4×5 Type 55 film formats. Now published by TBW Books, Tender spans photographs taken between 1984 and 1999. The collection collapses time through a body of unapologetically vivid work – playful, provocative, and present. The intimate self-portraits reveal the evolution of her gaze, reclaiming, redefining, and becoming, charting her coming-of-age as an artist and a queer Black woman. Winner of the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation First Photobook Prize and celebrated with a solo exhibition at Higher Pictures, Carla Williams: Circa 1985 marks the first time much of this work has been published or exhibited.

6. Magdalena Wywrot, Pestka

Deadbeat Club

When I look back on photos of myself as a child, they’re worlds apart from the grainy, high-contrast black-and-white images Magdalena Wywrot created in her project about her daughter, Barbara. These are far less sanitised and reflect the otherness of the universe Wywrot creates in Pestka – a name that means seed, shell, or kernel and is Barbara’s nickname. Accompanied by essays from David Campany and Barbara Rosemary, the series brims with a delicate intimacy yet hums with a raw, almost mystical energy. What began as a spontaneous act of documentation has become a richly layered work of magical realism and gothic narrative. Fragmentary and cinematic, the images possess a haunting poeticism that we might find in the avant-garde sensibilities of Vera Chytilová or Dušan Makavejev – full of the playful, subversive potential that Campany mentions in his text.

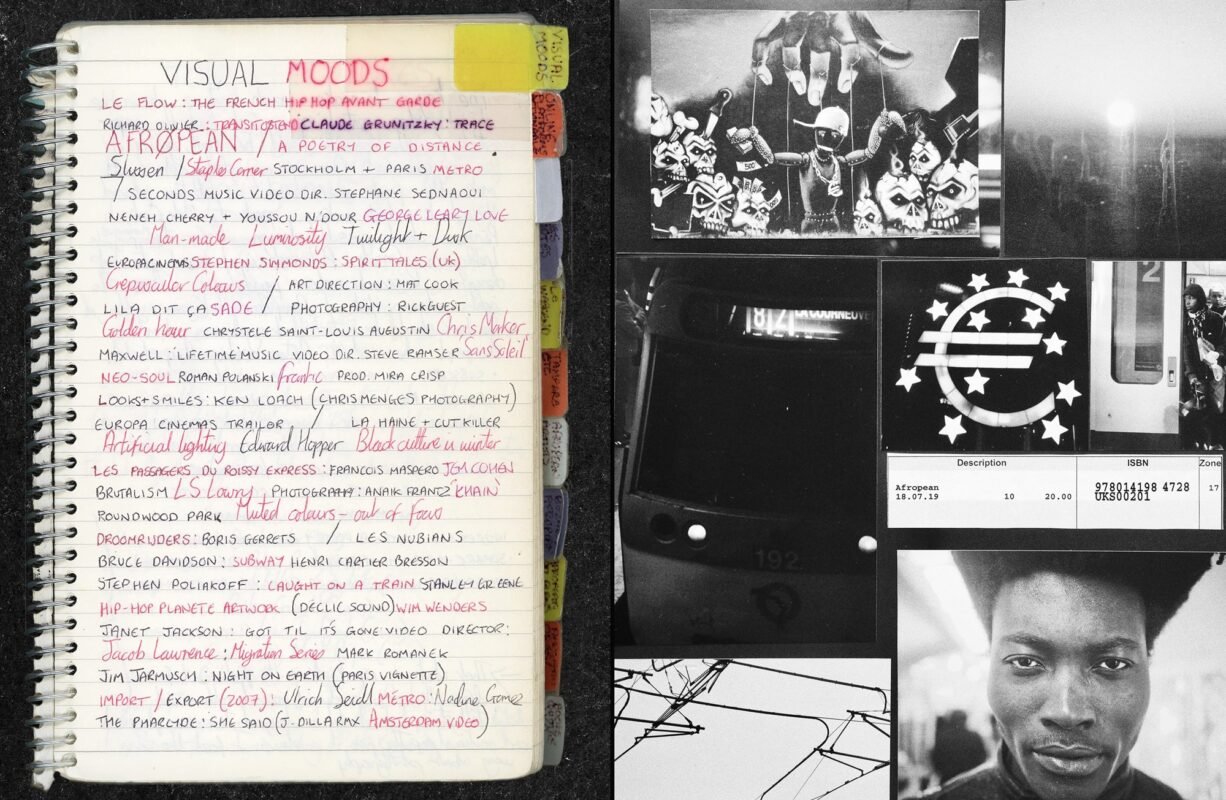

7. Johny Pitts, Afropean: A Journal

Mörel Books

Johny Pitts, founder of afropean.com and author of Afropean: Notes from Black Europe (Penguin, 2020), unites his expansive work in this thoughtfully curated photobook tracing a five-month journey encompassing Paris, Berlin, Lisbon, Brussels, Amsterdam, and Stockholm. Pitts, in his search for a different side of the continent, collates an epic travelogue that blends striking photography with personal ephemera – tickets, diary notes, maps, postcards – offers a tactile, immersive book that flies in the face of rising populism and far-right politics across the continent. New essays by Pitts deepen the conversation on the Black European experience alongside a six-part podcast, a soundtrack, and three short films shot on location – a bold, multi-layered exploration of Afropean life.

8. Ute Mahler, Werner Mahler, Ludwig Schirmer, Ein Dorf 1950–2022

Hartmann Books

Michael Grieve writes, ‘time, of course, is the great force here,’ in Ein Dorf 1950–2022; that force brings ‘an arbitrary photographic topography brought to reason.’ The village of Berka, Germany, has been captured over seven decades by three remarkable photographers united by a family story – coincidental or not – that ties together personal history with the sweeping political shifts from state socialism to the reunification of a divided country. Alongside essays by Jenny Erpenbeck, Steffen Mau, and Gary Van Zante, the 220 black-and-white images glimpse the subtle yet seismic moments that have redefined the village, its people, and its evolving identity. Here is a rivetting perspective, as sociological as it is a documentary, on a place that has witnessed history, and its political reality unfolding in real-time. Since we published our review, Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler have deservedly been awarded the Order of Merit of the Federal Public of Germany (2024) for services to photography.

9. Olivia Arthur, Murmurings of the Skin

VOID

After gracing festivals, museums, and galleries worldwide, Murmurings of the Skin now emerges as a striking publication from the mighty VOID. Nealy eight years ago, Olivia Arthur began her work on physicality, capturing the energy flowing through bodies and the sensation of skin on skin. Sparked by her experience of pregnancy, the work blossomed into a vivid exploration of youth, sexuality, and touch – charged moments of intimacy. In the stillness of pandemic isolation, these themes gained new urgency. The result is a tactile, sensitive work that remedies the struggle of feeling at home in our skin.

10. Máté Bartha, Anima Mundi

The Eriskay Connection

“Our world right now operates in code. So, if we’re talking about code, isn’t everything about how the universe functions?” There’s no denying that Máté Bartha’s latest work, Anima Mundi, leans into the obscure. If we begin with the title’s translation, Anima Mundi means “world spirit,” a concept rooted in Platonic thought, reflecting an ancient idea of a universal organising principle that connects all beings. Divided into chapters exploring urban phenomena ranging from the microcosmic to the cosmic, Anima Mundi composes intricate patterns, layered grid structures, and cryptic visual codes. Its poetic and philosophical approach to the desperate act of seeking structure and meaning invites us to return to the question: how do we make sense of the universe and its code? How do we find sense in arbitrariness?

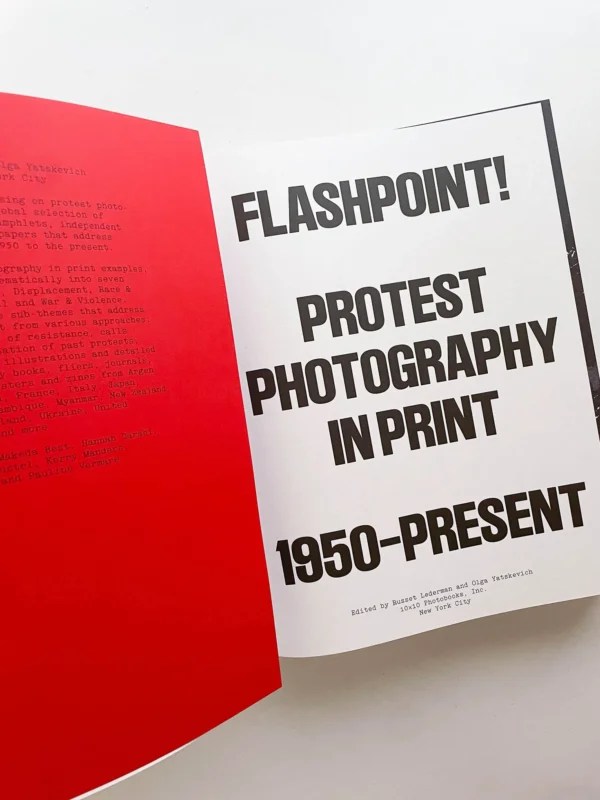

+1 Flashpoint! Protest Photography in Print, 1950-Present

10×10 Photobooks

What is the relationship between visual culture and protest? Flashpoint!, both a powerful survey of activism and visual tour de force, is a meticulously curated, global collection of protest photography, zines, posters, pamphlets, and independent publications from the 1950s to the present. The latest offering from 10×10 Photobooks is born from the 2017 project AWAKE: Protest, Liberty, and Resistance collection, which organised protest photobooks by themes through an open call. Flashpoint! builds on this with seven expansive chapters, each containing multiple sub-themes. Across 500 pages, 750+ images, and a series of thought-provoking essays, the endlessly evocative collection reflects Arthur Fournier’s ‘aesthetic of urgency,’ contrasting the polished, institutional protest imagery with the raw, time-sensitive visuals of grassroots movements.♦

—

Thomas King is Editorial Assistant at 1000 Words and a student on BA (Hons) Culture, Criticism, Curation at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London.

Tim Clark is Editor in Chief at 1000 Words and Artistic Director for Fotografia Europea in Reggio Emilia, Italy, together with Walter Guadagnini and Luce Lebart. He also teaches at The Institute of Photography, Falmouth University.

Images:

1-Cover of Adam Broomberg & Rafael Gonzalez, Anchor in the Landscape (MACK, 2024). Courtesy MACK

2-Adam Broomberg & Rafael Gonzalez, Anchor in the Landscape (MACK, 2024). Courtesy MACK

3-Karolina Spolniewski, Hotel of Eternal Light (BLOW UP Press, 2024). Courtesy BLOW UP Press

4-Agnieszka Sosnowska, För (Trespasser, 2024). Courtesy Trespasser

5-Carmen Winant, The Last Safe Abortion (Self Publish, Be Happy, 2024). Courtesy Self Publish, Be Happy

6-Carla Williams, Tender (TBW Books, 2024). Courtesy TBW Books

7-Magdalena Wywrot, Pestka (Deadbeat Club, 2024). Courtesy Deadbeat Club

8-Johny Pitts, Afropean: A Journal (Mörel Books, 2024). Courtesy Mörel Books

9-Werner Mahler, Ein Dorf, 1977-78 in Ute Mahler, Werner Mahler, Ludwig Schirmer, Ein Dorf 1950–2022 (Hartmann Books, 2024). Courtesy Hartmann Books

10-Olivia Arthur, Murmurings of the Skin (VOID, 2024). Courtesy VOID

11-Máté Bartha, Anima Mundi (The Eriskay Collection, 2024). Courtesy The Eriskay Collection

12-Flashpoint! Protest Photography in Print, 1950-Present, edited by Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich (10×10 Photobooks, 2024). Courtesy 10×10 Photobooks

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique, and activism.

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age.

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect.

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries.

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto.

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous R. Dahmani.