Radical approaches towards the archive

Co-curated by Impressions Gallery and Peckham 24, Performing Histories / Histories Re-Imagined features works by eight photographers who reframe official and personal archives to explore the abuses of organised religion and colonialism. As Anneka French writes, the exhibition’s diversity of influences underscores the role and value of the archive and, more crucially, the importance of radical approaches towards its reuse and interrogation.

Anneka French | Exhibition review | 1 August 2024

A statue of the Virgin Mary repeated across two photographs is a potent signifier of the power structures and abuses that inform and then I ran (2023). This suite of photographs, in which experiences of Emi O’Connell’s grandmother are re-enacted, is hung formally, with a central diptych of a blurred, brooding landscape flanked by figures in this same location. Described as ‘performative self-portraiture’, O’Connell re-tells parts of her grandmother’s story of escape from an Irish Catholic mother and baby home – often referred to as the Magdalene Laundries, institutions in which the devastating treatment of those confined is still coming to light – when she climbed from a window aged 16 and heavily pregnant with O’Connell’s father, who was subsequently forcefully adopted. O’Connell can be seen tenderly holding a sprig of cow parsley in one photograph. She can further be seen running, falling and twisting, her head bent and body crouched in distress, in images that are as strangely still, sensitive and beautiful as they are full of trauma.

The visible shutter release cable in O’Connell’s photographs is evidence of the reconstruction taking place and indeed, and then I ran embodies many of the core subjects presented in the wide-ranging and complex group exhibition Performing Histories / Histories Re-Imagined at Impressions Gallery, Bradford. The exhibition asks questions about the impacts of ‘official’ archives, be these institutional or familial, on (but not limited to) communities, bodies, memories and identities. Eight photographers here disrupt, re-make, re-present or reinterpret these narratives, finding meaning of their own and revealing new ways of looking at difficult things.

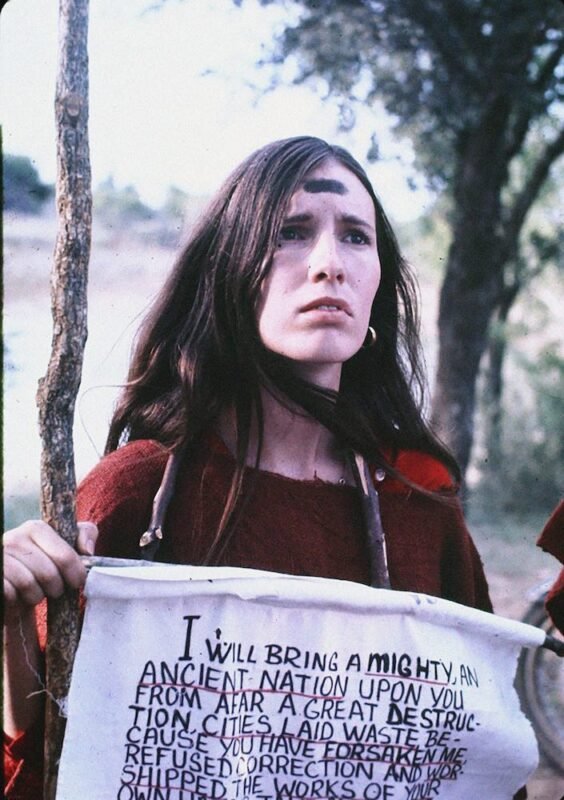

As with O’Connell’s photographs, the unfathomable impacts of and abuses by organised religion also occupy key roles in works by Alba Zari and Jermaine Francis. Zari’s Occult (2019-23) offers a partial picture of her own mother and grandmother’s life as members of a Christian fundamentalist sect now titled The Family International, in India, Nepal and Thailand. This is revealed through archival photographs, and comic strip-like drawings and text that highlight ways the sect drew in recruits through practices of sexual exploitation very much at odds with the smiling family photographs that Zari has layered on top of and tacked-up alongside these.

Francis’ Once Upon a Time: a bible, multiple protagonists and the propagation of gospel in racial time (2024-ongoing) is shown in and on vitrines arranged in the shape of a cross. The work itself is focused upon Anglian Church archives held by the Bodleian Library, Oxford, pertaining to historic missionary initiatives in the Caribbean. Underscoring the abuses of black people under colonialism and its continuing reverberations, Francis’ work, elements of which are placed beneath magnifying sheets, and including grey archive boxes, bibles and layered prints made up of collaged archival imagery and text, asks viewers to lean over, look closely and implicate themselves within the work and its contexts.

Also working with found archival imagery, Amin Yousefi’s Eyes Dazzle as They Search for the Truth (2022) uses protest photographs from the Islamic Revolution of 1978-79 in Iran. Specifically searching out people from the crowd who look (or seem to look) directly at the camera, these isolated individuals form a newly reassembled archive of gazes photographed through a loupe. Extracting individual people from the crowd, the work presented features a cluster of small prints alongside one very large photograph that centres the wary face of a young child, pinpointing his smallness and his humanity among the protesting throng.

Woman Wearing Ring Shields Face from Flash (2019-23) by Odette England is comprised of a large paste-up and a series of glossy prints. On the left, the photographs are of male photographers, prominent camera lenses and flashbulbs standing in place of eyes as their cameras obscure their faces. On the right are photographs of women refusing to be photographed, their hands in front of their faces and heads turned away. England’s work flags the potential abuses of photography itself – how it takes, snaps, shoots and captures through the violence of vocabulary hidden in plain sight – and of the subject’s own limited power in this dynamic. England’s work assembles vernacular images, forming a new archive of resistance that speaks to contemporary feminist dialogue and ongoing challenges to patriarchal perspectives that seek to control women in body and in image.

Eleonora Agostini’s and Tarrah Krajnak’s works touch upon further feminist concerns in connection with personal identity. While Agostini’s collection of photographs A Study on Waitressing (2020-24) pays homage to her waitress mother, her sore feet and the dual performances of in/visibility necessary to her role, Krajnak’s SISMOS79 (2014) explores her identity as an Indigenous transracial person who has experienced adoption and generational trauma. Composed of five large prints, Krajnak’s work combines broken mirrors photographed in conjunction with political and pornographic magazine pages from the year of her birth, offering a highly fragmentary personal and social perspective of this window in time.

Of all the eight photographers featured, Laura Chen’s work sits rather differently. Employing a dark sense of humour, Being Framed (2022) uses the rudimentary tropes of old-fashioned, analogue criminal investigations by police or private detectives popularised in film noir to develop a fictional case lead by avatar DCI Dean Wilson. Newspaper clippings, mocked-up case files, crime scene tape and a missing rabbit poster feature in Chen’s new archive. An image of a CCTV camera is positioned high up on the wall, while a footprint is playfully glued to the floor. Since Being Framed overtly refers to imagined or fictional events, it lacks the emotional and psychological force of other works on display.

The exhibition, which draws upon multiple international contexts and inputs, is co-curated by Impressions Gallery and Peckham 24, where it showed along with other projects and exhibitions in southeast London earlier this year. In Bradford, the exhibition’s diversity of influence, approach and subject makes for a challenging and, at times, uneven viewing experience but nonetheless it is one that serves as a useful reminder of the importance of the archive and, more crucially, of the importance of radical approaches towards it. ♦

Performing Histories / Histories Re-Imagined runs at Impressions Gallery, Bradford, until 31 August

—

Anneka French is a Curator at Coventry Biennial and Project Editor for Anomie, an international publishing house for the arts. She contributes to Art Quarterly, Burlington Contemporary and Photomonitor, and has written and had editorial commissions from Turner Prize, Fire Station Artists’ Studios, TACO!, Grain Projects and Photoworks+. French served as Co-ordinator and then Director at New Art West Midlands, Editorial Manager at this is tomorrow and has worked at galleries including Tate Modern, London, and Ikon, Birmingham.

Images:

1-Untitled from Occult, 2019-23. © Alba Zari

2-Untitled from A Study in Waitressing, 2020-24. © Eleonora Agostini

3-Emi O’Connell, and then I ran, 2023.

4-Untitled from Once Upon a Time: a bible, multiple protagonists and the propagation of gospel in racial time, 2024-ongoing. © Jermaine Francis

5-Untitled, from the series Eyes Dazzle as they Search for The Truth, 2022. © Amin Yousefi

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique and activism

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous Dahmani

• Shana Lopes reviews Agnieszka Sosnowska’s För

• Valentina Abenavoli discusses photobooks and community

• Michael Grieve considers Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler’s posthumous collaboration with their late family member

• Elisa Medde on Taysir Batniji’s images of glitched video calls from Gaza