Exile as a shared human experience

Spread across four floors of a Bristol townhouse, Amak Mahmoodian’s recent One Hundred and Twenty Minutes exhibition transforms the space into a chronotopia, writes Max Houghton – where many times, places and stories co-exist, and memories materialise out of nowhere. Fragments of countless lives emerge through photography, sketches and the quiet intimacy of shared dreams, all shaped by Mahmoodian’s 14-year experience of exile – a condition that continues to drive her work. Profoundly reparative, it invites us to see exile not as a marker of difference, but as a shared human experience.

Max Houghton | Exhibition review | 13 Feb 2025

Amak Mahmoodian’s recent show for Bristol Photo Festival 2024 recedes like a dream. Fragments remain … a feeling, hard to define, endures … awakening. You emerge changed. But the world is the same. The work in One Hundred and Twenty Minutes rises from below the ground. The first steps are into the unknown. Flickering light emanates from a dark cellar. This is where the dreaming begins.

Mahmoodian’s work is more experience than exhibition – a feeling more than a showing. Since 2019, she has been researching the psychological aspects of dreaming, and their connection to the condition of exile that has shaped her own life for the past 14 years. Born in Iran, unable to return due to the brutally extreme confines of its political regime, the solitude of exile bears ever more heavily. Since Mahmoodian left Shiraz, her mother is present in her life as FaceTime image on a screen, and in poems she writes to her daughter. Her physical absence in the space of the show is almost palpable as one of the many severed bonds, perhaps the most primal.

Photography transcends all its borders in this profoundly affecting work. Sketches, polaroid, poetry, video, still images, text; each forms a layer of meaning, or, (again), feeling. A spectral memory palace is constructed across four floors by Mahmoodian, in which the dreams of 16 people living in exile in the UK illuminate its walls. Over time, Mahmoodian listened to the stories of their dreams, and as first response, drew a sketch of its essence. Then, in a kind of alchemy, she constructed a photographic image; an image of an image. They appear here as offerings, rather than representations. The nature of the collaboration keeps a sense of the artist within the images, yet her role is closer to that of a conduit or a medium.

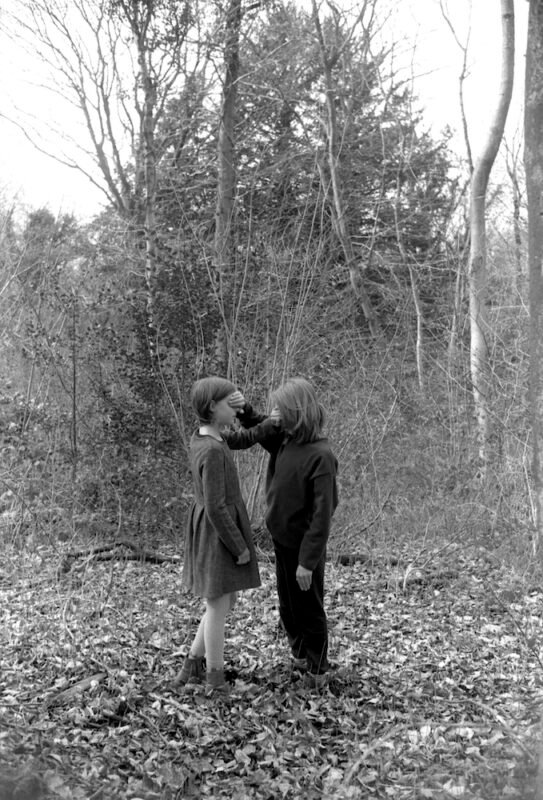

The images vibrate with texture, gesture, uncanny doublings, triplings – acts of translation in which a dreaming becomes a listening becomes a seeing. Displayed at different sizes and scales, mixing colour with black and white, they materialise from the walls as blinded statue, snake, ethereal dress, forest. And the ticking of a clock. There is no sense of unity or conformity within the images, but they are yoked together across two rooms and a set of stairs, by an unbroken line of sentences, perfectly positioned at the height of the cornice, which offer clues to the unconscious register: ‘As I go closer, I see she is losing body parts. I am scared. My belly button opens and I give birth to a fist. The stairs form a never-ending bright path. There are snakes everywhere.’

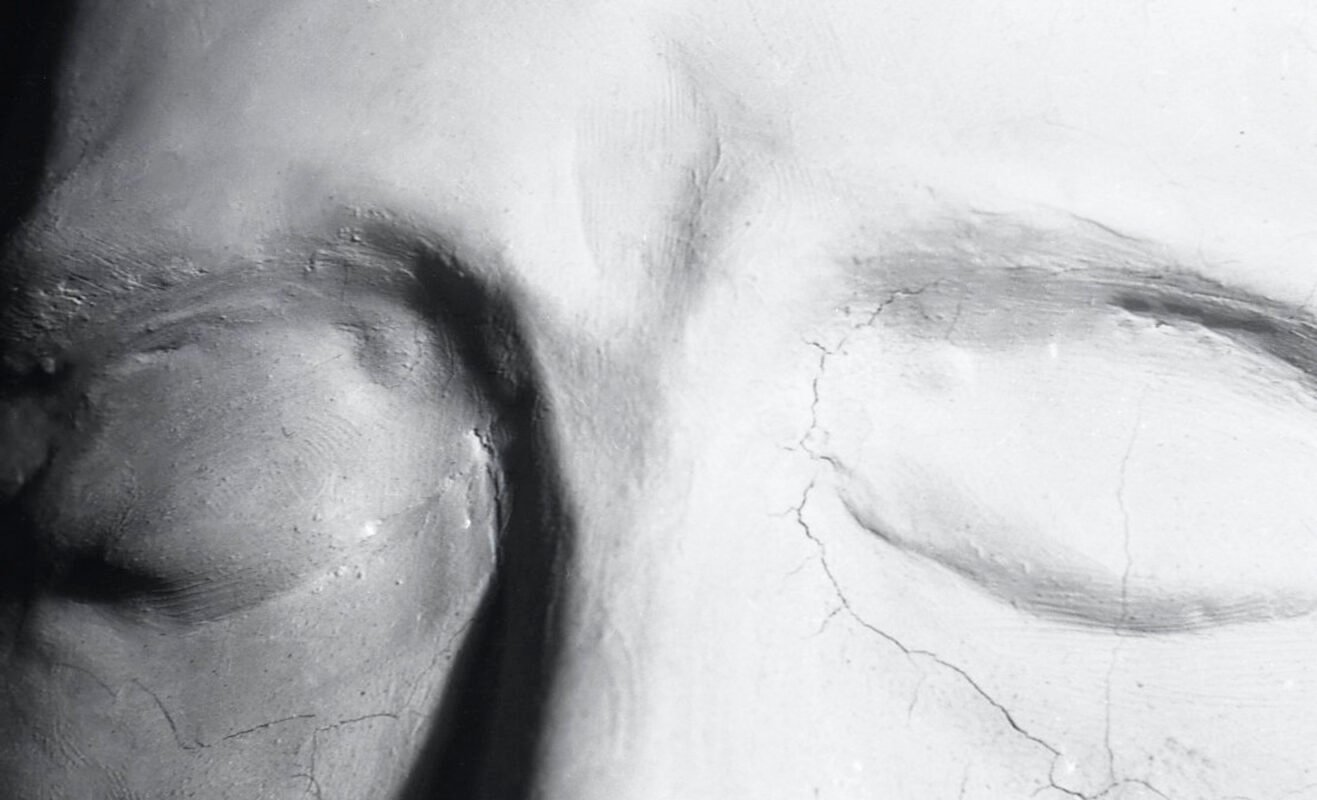

The ground floor is the grounding space. Here are vitrines displaying Mahmoodian’s sketch books – she calls them the heart of the work – polaroids, too, their instantaneity punctuating the deep time of exile. A poem, by the artist, reveals the work’s title: one hundred and twenty minutes is the time we spend in REM sleep each night. Below ground, the act of dreaming is shared too. Downstairs, in the dark, the viewer encounters a single screen, the camera trained on the face of a woman, asleep. Watching someone as they sleep is most usually a private act, occurring between a parent and a child, or between lovers. The intimacy of this spectatorship – there is room for just two people – sets the emotional tenor of the work as a whole. Dreaming eyes seem to be scanning lines, searching the archive, trying to locate the self, a place to which they can return upon waking.

During the show’s run, the space was activated for performance, and for meditation. It is as though it has been curated to animate conversation; thoughts turn to loss, and love and mourning. The four-storey town house on Midland Road has become a chronotopia, where many times, many places and many stories co-exist, and memories materialise out of nowhere (or somewhere to which you can’t return. Or someone). The making of work, the intensity of its subject, took a toll on Mahmoodian’s health a couple of years ago. She began to dream the dreams so carefully described to her, while her body kept the score. It coincided with the rise of far-right rhetoric intended to ensure that UK soil became a hostile environment for people who had crossed its borders to seek refuge. The work she has created is ultimately reparative, spiritual, even, as it seeks commonality instead of inscribing difference.

Edward Said, in his own work on the condition of exile, After the Last Sky: Palestinian Lives (1986), with photographs by Jean Mohr, wrote: ‘These photographs are silent; they seem saturated with a kind of inert being that outweighs anything they express, consequently they invite the embroidery of explanatory words.’ Mohr’s black and white photographs offer quiet visual testimony to the conditions that created the exile of the Palestinians. Mahmoodian’s work expands the register of the photography of exile with her luminous imagery, which seems to dwell in the realm of the unconscious. There are no explanatory words, because they are still being formed, still uncertain. Time has become non-linear, and, as the Surrealists expressed, seemingly disconnected objects and ideas appear on the same plane of seeing. Mahmoodian has tapped into the psychological and emotional power of the image to reveal the longing and the loneliness of exile, and the threat of violence that caused it and underpins it still.

The questions Mahmoodian wanted to raise in terms of whether there are similarities in the nature of the dreams of exiled people are not for me to answer. But among the achievements of One Hundred and Twenty Minutes is that the exploration of the question has conferred a sense of community among the participants, which is needed and desired by all involved. The work also expands the definition of what we understand as an image, or, rather, it throws a lifeline between a mental image and a material one. It might be that within this process is a small raft for survival. ♦

Amak Mahmoodian: One Hundred and Twenty Minutes ran until 17 November as part of Bristol Photo Festival 2024.

—

Max Houghton is a writer, curator and editor working with the photographic image as it intersects with politics and law. She runs the MA in Photojournalism and Documentary Photography at London College of Communication, University of the Arts London, where she is also co-founder of the research hub Visible Justice. Her writing appears in publications by The Photographers’ Gallery and Barbican Centre, as well press such as Granta, The Eyes, Foam, 1000 Words, British Journal of Photography and Photoworks. She is co-author, with Fiona Rogers, of Firecrackers: Female Photographers Now (Thames and Hudson, 2017) and her latest monograph essay appeared in Mary Ellen Mark: Ward 81 Voices (Steidl, 2023). She is currently undertaking doctoral research into the image and law at University College London. She was the 2023 recipient of the Royal Photographic Society award for education.

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique and activism

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous Dahmani

• Shana Lopes reviews Agnieszka Sosnowska’s För

• Valentina Abenavoli discusses photobooks and community

• Michael Grieve considers Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler’s posthumous collaboration with their late family member

• Elisa Medde on Taysir Batniji’s images of glitched video calls from Gaza