The 9th Singapore International Photography Festival

Loosely inspired by Marcel Proust’s epic modernist classic, The 9th Singapore International Photography Festival, under the title In Search of Lost Time, considers photography as a carrier of both personal and national identities. Featuring FX Harsono’s Keeping the Dream, which confronts ethnic subjugation in Indonesia through archival portraits of Chinese Indonesian children; Liu Bolin’s Seeing the Invisible, presenting staged self-portraits that merge him with urban landscapes; and Mingalaba: A Journey Through the Myanmar Photo Archive, curated by Kirti Upadhyaya, which intertwines public and private narratives of Burmese life through family portraits and civilian records. The festival surfaces involuntary gaps in history, memory and documentation, holding a mirror up to the process of self-examination itself, Kong Yen Lin writes.

Kong Yen Lin | Festival review | 31 Oct 2024

Interposed between physical reality and representation, photographs are often carriers of biographies, be it the self or the nation, which germinate in varying social contexts bearing new meanings for their beholders. The biennial Singapore International Photography Festival (SIPF) is an intensification of this capacity for introspection. In surfacing photography’s layered possibilities vis-à-vis the medium’s manifestations as photobook, research data, archival records, and vernacular keepsakes, it prompts deeper thought about the sociocultural fabric of Singapore and our ever-changing identities in an age where visibility, memory, time and space are constantly being redefined.

Framed by a curatorial direction loosely inspired by Marcel Proust’s epic modernist classic In Search of Lost Time (1913), bodies of works presented similarly grappled with the protean nature of memory as frozen or compressible, allowing revisiting and reflection, or fluid and meandering, changing and reshaping as new interpretations are added to them.

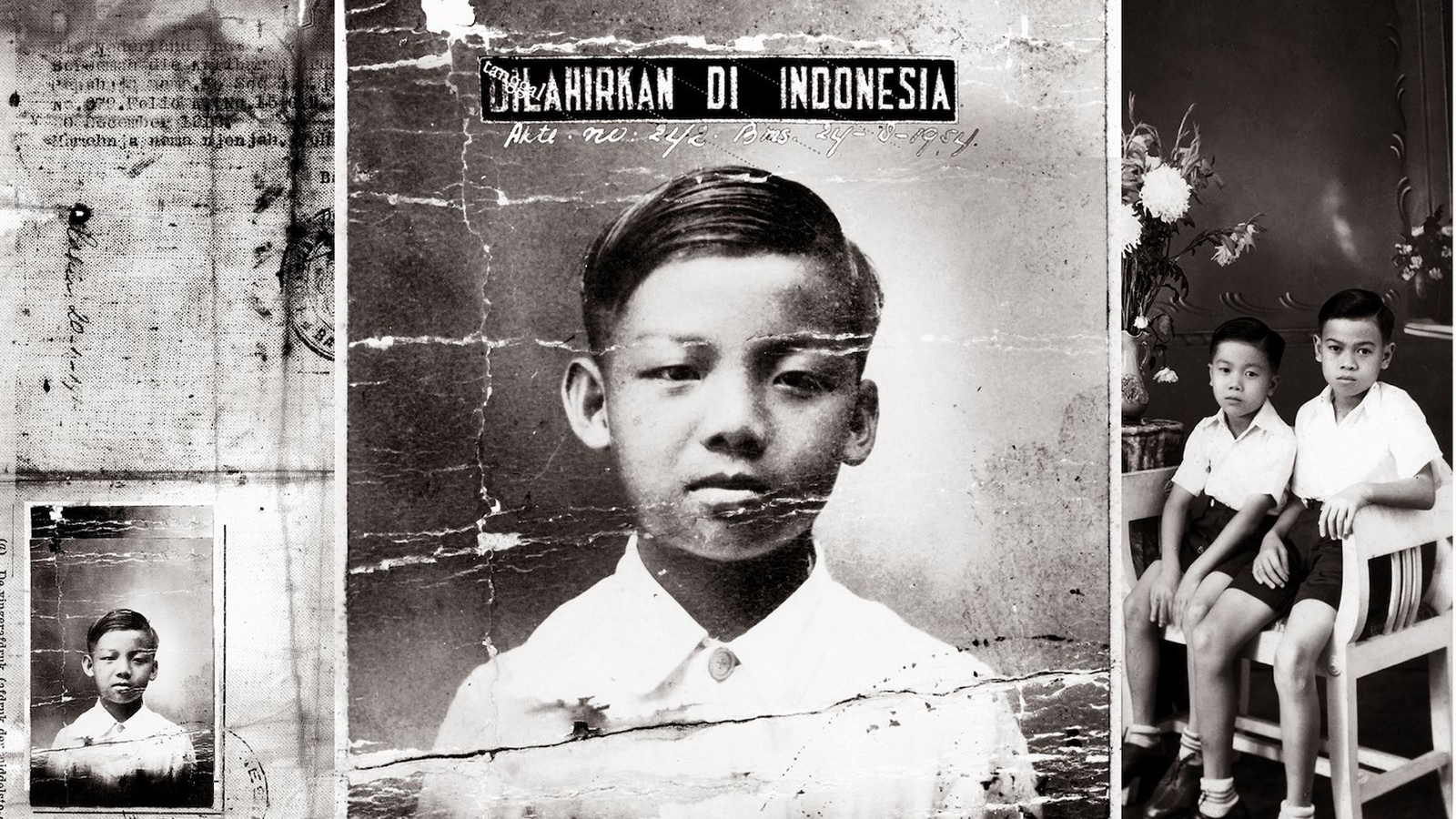

A fitting primer to the festival is Keeping the Dream, a festival commission featuring Indonesian contemporary artist FX Harsono, which asserted the inherent violence in photography when being deployed as an apparatus for ethnic profiling and subjugation. Known for his politically charged works which examine identity through a personal lens, Harsono critiques the long-standing institutional discrimination and oppression of the Chinese minority community in Indonesia (of which he is a member). Taking centerstage is a typology of over 100 archival facial portraits showing anonymous Chinese Indonesian children, ranging from toddlers to pre-teens, extracted from official identification documents dating from early to late 1990s which he had been salvaging since a decade ago. They allude to state policies during Former President Suharto’s New Order regime that required ethnic Chinese Indonesians to undergo onerous proof of citizenship, as well as measures which suppressed the expression of Chinese identity, such as banning the public use of Chinese names and forcing civilians to adopt Indonesian ones.

Together with a series of photo assemblages juxtaposing ID documents with found images of familial bliss, Harsono projects his imagination of a childhood unfettered by prejudice and surveillance that might have elided most children of that generation. The absence of textual labels providing translation support for the documents rendered in Dutch or Bahasa Indonesia, echo the silences of a community facing erasure. Yet the artist’s act of resurfacing these records and reinterpreting them with personal interventions stood in defiance of this painful period in history from being forgotten. Reflecting on the Singaporean context, a city state with a population comprising 76 percent ethnic Chinese, the governance of Chinese identity, language and culture had also been instrumentalised and calibrated to balance delicate geopolitics of its position within the Malay Archipelago, and the need to remain connected to China’s economic success.

The exploration of identity as a sociopolitical construct continues in Seeing the Invisible, a solo exhibition by Chinese artist Liu Bolin featuring 11 works from his ongoing Hiding in the City and Target series. Conceived using painting, performance and photography, these staged self-portraits depict Bolin literally blending into the backdrops of selected landscapes. Adopting the visual metaphor of invisibility, they provoke thought on the marginality of identity and memory arising from tensions between insider and outsider, individualism and collectivism. While Bolin’s impetus to begin Hiding in the City originated in 2005 as personal protest sparked by the government’s forced demolition of his artist studio in preparations for the Beijing Olympics, over the years, his choice of canvases and collaborators have come to reflect a far-ranging humanistic concern. For one, Cancer Village (2013) involved the artist collaborating with over 20 villagers in Shandong province facing the threat of downstream industrial pollution, to stage an act of camouflage against a desolate wheat field, with the aim of raising awareness around the social costs of economic progress. As part of a festival commission, Bolin had also created two new site-specific artworks in Singapore, poised against the touristic landmark of the Merlion Park and a bustling Hawker Center in Chinatown.

The latter was particularly meaningful for Bolin, who felt it “embodied the historical lineage of Chinese migration across the world” [1]. His profile as a Chinese artist intermingles with the cultural politics of Singapore’s Chinatown, which is an anomaly from most Chinatowns in the world typically catered for the Chinese minority of the populace. During 19th to mid-20th Century British colonial rule, Chinatown was a self-sustaining ethnic enclave demarcated for incoming Chinese immigrants. However, in post-colonial Singapore, its significance evolved to embrace the nation’s multicultural outlook, and developed into a site of active discourse on gentrification and heritage preservation. With globalisation, complexities of identity, memory, and integration came into sharp relief when Chinatown relived its role as a point of congregation for the post-1990 wave of new Chinese immigrants to Singapore [2]. Furthermore, hawker centres are also unique social spaces in Singapore that stand for the melting pot of diverse food cultures.

Expanding this dialogue with the cultural politics of space was Mingalaba: A Journey Through the Myanmar Photo Archive / မင်္ဂလာပါ: မြန်မာ့ဓာတ်ပုံမော်ကွန်း၏ဖြတ်သန်းခြင်းခရီး , a photographic display curated by Kirti Upadhyaya. Inserted into shop displays, advertisement niches and restaurant walls across a cluster of malls in the city’s central district, doubling up as bustling enclaves for the sizeable Burmese community in Singapore, the archival images represent a historical counterpoint against the flux of activities in the spaces. The mix of images ranging from mid to late 20th Century vernacular snapshots, family photos, studio portraits, and civilian records of national milestones such as the first independence speech in Yangon in 1948, not only crisscross terrains of personal and social memory, but also blur boundaries between the private and public. Collections by two of the earliest local photographers U Than Maung and U Aung San were especially captivating, offering a rare glimpse into identity formation and self-fashioning in post-colonial Myanmar.

The Myanmar Photo Archive was founded almost a decade ago by Austrian photographer Lukas Birk when Myanmar was loosening up from decades of oppressive military rule, with the aim of creating a repository of social and personal memory. The display posits deeper contemplation on the photograph as a construct of contextual interpretation, and its role in historical imagination and retelling. Within Yangon’s highly restricted and fraught media landscape, it entails greater democratic access to the past, though navigating with silences, absences and information gaps remains a perennial challenge.

This atomising of the stream of life into discrete, manageable elements to be collected, saved and shared, extends beyond traditional archives into the virtual multiverse of social media, as examined in Pierfrancesco Celada’s solo exhibition. It comprised three bodies of works When I feel down I take a train to the Happy Valley, One a Day and Instagrampier, which were executed in tandem during the time he lived in Hong Kong from 2014 to 2022. Bearing witness to recent momentous events in the city such as the Umbrella Movement and the global pandemic, Celada poses an observation into psychosocial realities of one of the world’s most densely populated urban metropolises. His approach is gently curious and non-didactic. Images seized from spontaneous moments on the streets, appear enigmatic and open-ended, inviting audiences to project their own interpretations. Instagrampier (2016-2021), a series which unfolded within a cargo pier on the west side of Hong Kong island, stood out in particular for its wry take on how the gaze of content sharing platforms such as Instagram, imposes a visual logic to the world of images through approval metrics. While initially setting out to document the constant streams of Instagrammers posing for selfies at sunset with similar stances and antics, Celada soon found himself caught in the loop of repeating the same ritual of recording others record themselves. “My works are self-portraitures of how I lived,” he said in an interview [3]. This calls to mind theorist Nathan Jurgenson’s remark of the social photo as ‘a documentary consciousness that turns users into a tourist of their own experience’ [4].

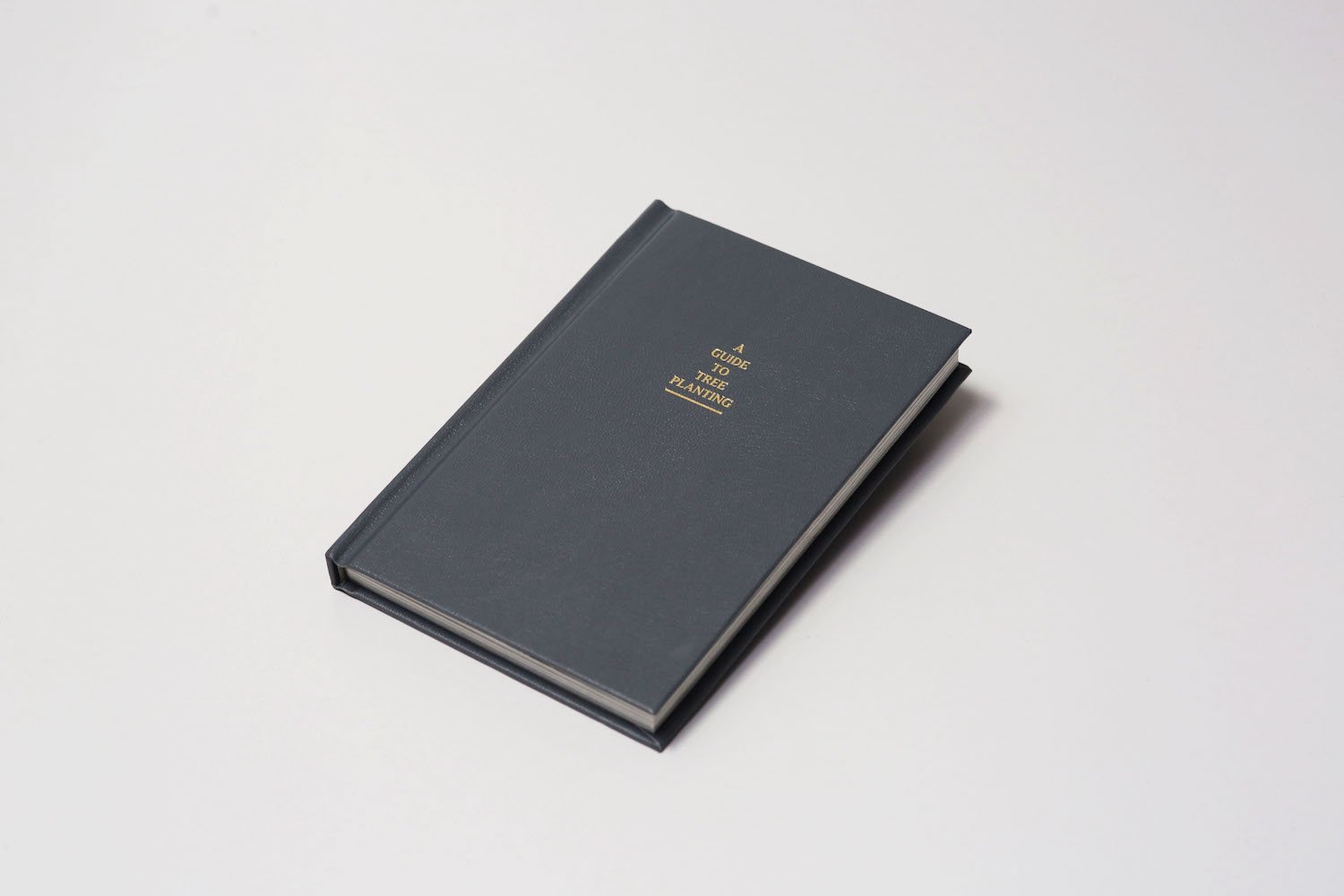

The power of the photographic gaze to objectify, possess, and turn life into something relatable and consumable is explored through Garden City: Remix Edition, a collaborative project by DECK and ArtSpace LUMOS that features four photographers – Woong Soak Teng and Marvin Tang from Singapore as well as Kim Sunik and Lee Jin Kyung from South Korea. The exhibition appraises the dialectics between humans and nature in urban living environments, and the many contestations and contradictions that arise from our ambition to document, tame, and co-exist with the natural world. Dialogues that arise between the works ultimately point towards the embodied experience of nature and the inseparability between nature and culture. By contemplating how ecological relationships are in fact socially constituted, the show summons deeper consideration on the types of attachment and values that undergird the relations one has with the self and with others.

Collectively, the festival surfaces involuntary gaps in history, memory and documentation, holding a mirror up to the process of self-examination itself. It reinforces the ever-critical role of art and photography to liberate from the buried world of spent consciousness, the many alternate pathways to the future to which habit has made us blind. ♦

Singapore International Photography Festival (SIPF) runs until 24 November 2024.

—

Kong Yen Lin is Assistant Curator, the National Museum of Singapore. Aside from her professional practice, she is a researcher and writer focusing on Singapore’s modern photography history from the 1950s to 80s, with an interest in examining the wider systemic frameworks governing the development of visual culture.

References:

[1] Interview with the author, 16 October 2024.

[2] Brenda S.A. Yeoh and Lily Kong, “Singapore’s Chinatown: Nation building and heritage tourism in a multiracial city” in Localities, Volume 2, 2012. https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/soss_research/2250, [accessed 27 October 2024].

[3] Interview with the author, 25 October 2024.

[4] Nathan Jurgenson, The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media (London & New York: Verso, 2020).

Images:

1-FX Harsono, Keeping the Dream No.3, 2024.

2- Installation view of FX Harsono, Keeping the Dream No.3. © Toni Cuhadi. Courtesy Singapore International Photography Festival and DECK.

3-Liu Bolin, Chinatown. Performance: 11-22 October 2024.

4-Liu Bolin, Chinatown Complex Hawker Centre. Performance: 11-22 October 2024.

5>7-Liu Bolin, Merlion Park. Performance: 11-22 October 2024.

8>10-The Myanmar Photo Archive

11>12-Pierfrancesco Celada, Instagrampier, 2021.

13-Pierfrancesco Celada, When I feel down I take a train to the Happy Valley, 2014-2022.

14-Marvin Tang, A Guide to Tree Planting.

15-Kim Sunik, Temporary Garden.

16-Woong Soak Teng, Some Pictures of Representation, 2018.

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique and activism

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous Dahmani

• Shana Lopes reviews Agnieszka Sosnowska’s För

• Valentina Abenavoli discusses photobooks and community

• Michael Grieve considers Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler’s posthumous collaboration with their late family member

• Elisa Medde on Taysir Batniji’s images of glitched video calls from Gaza