Photobook Conversations #7 | Luis Juárez: “Who gets to tell stories through this medium?”

Photobook Conversations is edited by Ana Casas Broda (Hydra + Fotografía), Anshika Varma (Offset Projects) and Duncan Wooldridge (Manchester Metropolitan University). Sitting alongside the earlier Writer Conversations (1000 Words, 2023), edited by Lucy Soutter and Duncan Wooldridge, and Curator Conversations (1000 Words, 2021), edited by Tim Clark, it completes the series exploring the ways our understanding and experience of photography is mediated through exhibitions, writing and publishing.

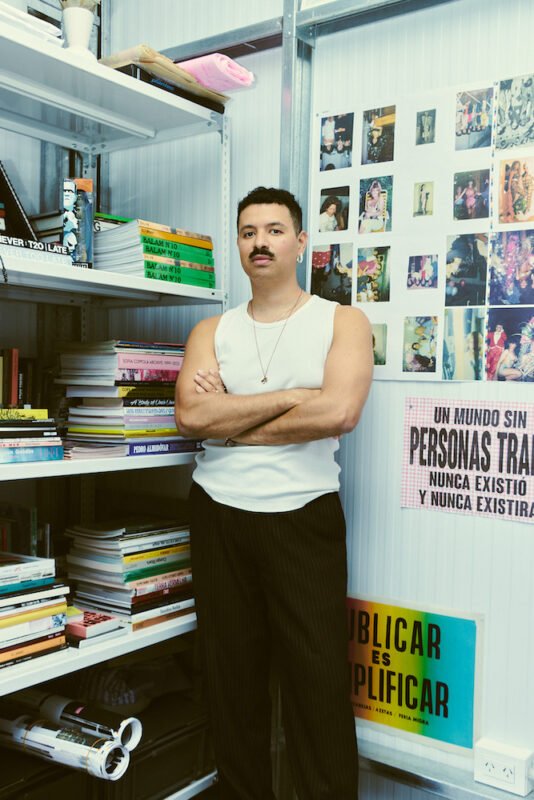

Luis Juárez | Photobook Conversations #7 | 6 March 2025

Luis Juárez is an editor, curator and cultural practitioner in the field of photography, based in Buenos Aires, Argentina. He manages artistic projects and produces books, magazines, exhibitions, and art fairs. He is the Editor and Director of Balam, the first and only queer magazine dedicated to contemporary photography in Latin America, and the Founder and Director of MIGRA, Buenos Aires Art Book Fair. Juárez is a member of Archivo de la Memoria Trans Argentina (Argentina Trans Memory Archive), a space for the protection, construction and vindication of the trans memory, where he coordinates its publishing house.

What were the encounters which started your relationship with photobooks?

The first time I had an idea of what it meant to create a publication was when I was 10 years old, in 2001. I was in fifth grade at my elementary school in Tegucigalpa, Honduras. My teacher assigned us the task of creating our own magazine. The magazine I made was about entertainment and music. I remember going to the print shop with my older sister. We stood in front of the place, surrounded by printing machines and stacks of paper, and I had to make decisions about how I wanted my magazine to look. Imagine the kinds of decisions a 10-year-old could make… The man at the print shop asked me what type of paper I wanted to use, what format I preferred, and how I wanted the magazine assembled. I remembered my sister telling me that she really liked my project. That moment marked my first, albeit unconscious, encounter with the role of editor and creator of printed matter. From then on, I developed a special interest and sensitivity for working with images and tangible objects.

Many years later, now living in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 2018, I managed to print the first physical edition of Balam, Issue N5. Its theme was ‘Metamorphosis’, where we explored how images inherently carry a drive towards change. We created a document that brought together images and reflected on their productive process, and the desire to represent transformation. In the issue, we included critical and aesthetic contributions that helped us envision a new habitat, a renewed space where differences became metaphors that generated meaning. We proposed a break from normativity, offering alternatives to conventional forms. Or at least, that’s what we aimed to convey. Metamorphosis was an experimental issue. My training as an editor has always been self-taught, and in this issue, I envisioned Balam for the first time as an object, more akin to the concept of a photobook than a traditional magazine. Although I call it a magazine, I appropriate the term to reimagine and understand what it means to work collectively.

The project began digitally in 2015, using the resources I had at the time: a computer and a desire to connect with photography. As a migrant without a single penny in my pocket, I later found a way to express myself through photography and paper. Migration, the lack of representation and the desire to create a space of connection outside the established norm were the excuses I needed to start making photobooks.

What is your process for arriving at decisions about books and the projects that you undertake?

In my case, directing a project that is printed once a year means working periodically. Each issue of Balam focuses on a specific theme, chosen through a deliberate and reflective process. The decisions about content are guided by a central goal: to speak relentlessly about the realities of sexual minorities and dissident communities. This focus is not accidental; since its first edition, Balam was born out of an urgent need to provoke, question and give visibility to voices that have been historically silenced or rendered invisible.

The world of photography – especially where the greatest capital and decision-making power are concentrated – has long been dominated by dynamics that privilege academic and intellectual white perspectives. This bias perpetuates exclusions and hierarchies that leave many on the margins. For me, understanding these structures is not only important but essential, as it allows me to offer a conscious and active response to the established order. I use photography as an excuse, a medium to debate, confront and question the realities of my community. Beyond its aesthetic value, the images in Balam are tools for initiating conversations, challenging narratives and exploring new possibilities for representation.

The books I produce are not just objects, but spaces for collective reflection. I am particularly interested in questioning who has access to photography and the production of photobooks. Who gets to tell stories through this medium? What economic, social or cultural barriers limit access? These questions guide my practice and reinforce my conviction that working in community is the only way that makes sense to me. The decisions that shape my projects emerge from collective processes. I interpret and materialise these decisions, acting as a bridge between the needs expressed and the creation of an editorial object that engages with those demands.

I often reflect on the disconnection between academia and the realities of communities. I believe sometimes academia lacks the “streets” in its epistemology. It is easy to analyse and theorise from the comfort of a desk, but going out into the world, putting your body on the line and experiencing the tensions of social realities is a completely different practice. I firmly believe that this connection to the ground, to living stories, is what gives meaning and depth to my work.

In Balam, themes are not only decided but also discovered in the midst of the creative process. By deeply immersing ourselves in the theme of the current issue, we uncover ideas and connections that organically lead us to the next edition. This makes the project something alive, constantly evolving. I like to imagine Balam symbolically as a necklace: each previous issue awakens and nurtures what the next one will become. For example, Issue N8: Chosen Families awakened issue N9: New Masculinities, and so on… This continuity ensures not only coherence but also a constant evolution in the discussions and reflections we propose.

How do you like to work with people?

For every issue, I collaborate with a guest editor. Together, we decide how we want to project and tell the story, from its concept to its materiality and design. This approach allows Balam to reinvent itself from scratch. Nothing about Balam is linear, because there is nothing straight. Each editor brings their own unique universe, inviting me into their world and challenging me to be even more politically incorrect. This process reaffirms that there is no single answer when it comes to creating and producing.

I’m not interested in working with “editors” in the traditional sense of the word. Instead, I collaborate with individuals whose connection to the proposed theme is deeply rooted in their way of life and personal experience. Their wisdom comes from lived experiences and emotional insight. This is crucial to me: learning from them, amplifying their capabilities and offering them a space to discover new possibilities within themselves. This exchange is mutual and deeply reciprocal. Without reciprocity, I’m not interested in collaborating; I cannot move forward.

As such, the selection of guest editors is never random. I choose to work with people I deeply admire and respect. These collaborations enrich me both personally and professionally, reinforcing my belief that creativity thrives in encounters and dialogues. By allowing each editor to bring their vision, the project becomes a platform for constant exploration. This methodology ensures that every issue is a unique and authentic exercise, where differences are not only celebrated but also become the driving force behind the creative process.

What is the public for a photobook? Who do you think of as your audience?

I would like to rephrase the question and reflect on “Who are the people doing photobooks?”. Instead of “What is the public for a photobook?”, who has access to the resources needed to make them? Access to information and production tools must be universal, regardless of the format. Only then can we truly work with perspectives that are more real, inclusive and representative.

It’s important to acknowledge that, historically, photography has been a tool of colonisation, used to document and illustrate what which was stolen from us. For example, in hundreds of photobooks created by white men, we find the story of colonisation in the Americas told from an external perspective, often stripped of context and the voices of its true protagonists. Now, imagine what happens when these books are printed and distributed across the world. In the past, we had no choice but to rely on these narratives to learn about “our history”. There is a canon of European and American photography that focuses on that, on celebrating the fetishisation of our territory.

Today, the dynamics have shifted, and we have a responsibility to challenge these narratives and actively work to bring photobooks closer to their rightful protagonists. It is time to stop telling stories that don’t belong to us and to cease appropriating others’ narratives. In my case, my interest in creating books and magazines is deeply rooted in working with the people who live and embody these stories. It’s about creating a safe space where they can tell their own experiences, from their own perspectives, and see themselves represented in the materials we produce.

This leads us to a crucial question: what does it really mean to create a photobook? Do we want our book to simply be a product that reflects our personal interests, celebrates the excellence of its materiality and design, wins awards and participates in prestigious festivals? Or do we want it to be a vehicle for amplifying voices, a means to provide resources to communities and projects that have long awaited the opportunity to be heard and seen?

If we choose the latter, we are engaging in an act of reparation and social justice – a way to contribute to greater integration and representation. This brings us to the pivotal question: are we truly creating new narratives in photobooks, or are we perpetuating the same structures of exclusion and centralisation of power?

In my case, before thinking about who my audience is or who the people consuming my books are, I focus more on the audience I want to work with. That is, I prioritise understanding the internal aspects over the external ones. When the focus is on the internal, the external result – the book as a final object – becomes a genuine reflection of the relationships, learning experiences, and conversations that took place during its creation. The external audience is simply a natural consequence of the final work. My attention is on the process – on how and with whom I work with.

How important is it for photobooks to reach other continents?

A photobook is much more than a physical object; it is the crystallisation of ideas, experiences, narratives, and collaborations. Reaching new corners in other continents is essential for these stories to be understood, read and appreciated from different perspectives.

I work with the idea that books should be free of borders – a tool to democratise other realities and expand the conversation beyond their places of origin. At Balam, for example, we translate our magazine into English, Spanish and Portuguese to connect with broader and more diverse audiences. This not only allows our stories to reach more people but also creates a space to find commonalities, shared interests and representations across cultures.

This effort of distribution and openness significantly expands our network, fostering collaborations with institutions, curators, artists and photography professionals from other countries. Reaching other continents is not just an opportunity for expansion; for me, it is a way to affirm and consolidate the ideals and methods I wish to work with. It gives me a perspective on how things are made and thought.

However, producing the book is not enough; circulation and distribution are equally important processes that require attention and planning. Books don’t move on their own. It is essential to build relationships and experiences with the people and places that make it possible to participate in fairs, festivals and other cultural events. Especially if you’re living in Latin America, where access to this industry is hard to be supported. So going abroad is essentially to position yourself and make new connections. In terms of financing, for us historically, the money and the funding support is abroad.

In my case, after printing Balam for the first time, I was faced with the need to figure out how to move this independent project into new spaces. That’s when I created MIGRA, Buenos Aires Art Book Fair. This project was not only a response to my own concerns but also a platform to connect with other projects and art book fairs around the world, like the Printed Matter Art Book Fair in New York City, SPRINT in Milan, Athens Art Book, Recreo in Valencia and many others. Generating alliances and collaborations that strengthen the independent publishing community.

This work doesn’t happen in isolation. It’s an ecosystem where every element – creating the book, distributing and showcasing it – is essential for the whole process to function. Without one, the others wouldn’t exist. And within this ecosystem, we’re not just sharing an object but a worldview – open to dialogue and transformation.

What do you think is the significance of the shift towards the book as an object?

The shift towards the book as an object represents a profound evolution in how we perceive, create and interact with publications. It transforms the book from being solely a vessel of content into a multidimensional artifact – one that embodies not only the narrative it carries but also its materiality, as well as design and tactile qualities. Treating the book as an object disrupts traditional publishing paradigms. It challenges the notion that books are merely functional or consumable, positioning them on a different scale from conventionalism. This shift often aligns with experimental and independent publishing practices, where we as creators have the freedom to reimagine whatever suits our projects best.

Creating, editing, printing and ultimately having a book read is, in itself, a performative act – a psycho-magic ritual that the photobook enacts. Each reader establishes a unique relationship with the book and its imagery, and for some, this connection becomes almost sacred.

When we print a photobook, we are working with the visual, engaging directly with what captures the eye first. This is where the emotional resonance of the work takes hold, forging an immediate, visceral connection between the viewer and the content. This process embeds the book with a profound affective dimension, making it inseparable from the individual who engages with it. Once this bond is formed, there’s no turning back; the book becomes part of the person, a reflection of their experience and perception.

Photobooks, as tangible objects, carry a symbolic weight that contributes significantly to our construction of identity. We create and surround ourselves with objects that resonate with us on a deeper level, shaping and reflecting who we are. A photobook, then, is more than just a collection of images or stories; it is a vessel of meaning, charged with the emotions, ideas and identities of both its creator and audience.

This is why photobooks are often cherished as personal artefacts, not just artistic creations. They occupy a unique space between the visual and the tangible, where their physicality enhances their narrative power. The act of holding a photobook, turning its pages, and immersing oneself in its images and textures transforms it into an intimate experience. It is not just a book; it is an extension of human expression, a dialogue between the creator, the object and the reader.

How do you attempt to address sustainability in publishing?

The question of how to approach sustainability in publishing is complex for me. I work with and produce books independently in a context where printing is becoming increasingly difficult. This is due to several factors, one of the main ones being the economic crisis in Argentina. Additionally, there is a lack of cultural support and a shortage of collaborative projects that contribute to strengthening the photobook community.

In Argentina, Balam is the only contemporary photography magazine currently published, and one of the few in Latin America. Over time, I have noticed that printing costs continue to rise, which increases the price of the magazine for the market. This forces me to constantly think about strategies and partnerships to keep the project afloat. In fact, one of the biggest challenges is that many projects, due to economic reasons, end up becoming obsolete and disappear.

Next year, Balam will turn 10, something I never imagined would happen, and it remains relevant and alive. This leads me to reflect on the concept of sustainability, which in my case is highly influenced by the context. It is not the same to edit and produce a photobook in Switzerland as it is in Argentina, as the resources, opportunities, materials and access are completely different.

I believe that an established publishing house or an institution might be able to address sustainability and answer this question better than me. In my case, it is much more complex, as I am uncertain about how I will be able to print the next issue of Balam. Sustainability in my practice is linked to constant uncertainty.

It is important to consider that, for those of us working independently, sustainability not only refers to the ability to maintain a project long-term but also to resilience in the face of an economic and social environment that makes cultural production difficult. Sustainability in publishing, for me, also involves building connections, strengthening networks of collaboration and supporting the creation of spaces that foster diversity and inclusion in the publishing industry.

What would make a better photobook ecosystem?

To go outside of it, to move beyond its own limits. It is essential to engage in dialogue with spaces, people and institutions outside of what is established. Working with the concept of decentralisation allows for the opening of other worlds and perspectives, creating new possibilities for creation and reflection. Agents who can play an active role in institutions, reviewing and questioning key aspects of the history of photography. I believe that photography gains greater meaning when one steps outside of it. It makes even more sense knowing that this is our medium of work.♦

Further interviews in the Photobook Conversations series can be read here

Click here to order your copy of the book

Images:

1-Luis Juárez © Hector Villalobos

2>3-Covers and spread from Balam

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique and activism

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous Dahmani

• Shana Lopes reviews Agnieszka Sosnowska’s För

• Valentina Abenavoli discusses photobooks and community

• Michael Grieve considers Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler’s posthumous collaboration with their late family member

• Elisa Medde on Taysir Batniji’s images of glitched video calls from Gaza