Photobook Conversations #6 | Anastasiia Leonova: “This ecosystem is vibrant, but it is also insular”

Photobook Conversations is edited by Ana Casas Broda (Hydra + Fotografía), Anshika Varma (Offset Projects) and Duncan Wooldridge (Manchester Metropolitan University). Sitting alongside the earlier Writer Conversations (1000 Words, 2023), edited by Lucy Soutter and Duncan Wooldridge, and Curator Conversations (1000 Words, 2021), edited by Tim Clark, it completes the series exploring the ways our understanding and experience of photography is mediated through exhibitions, writing and publishing.

Anastasiia Leonova | Photobook Conversations #6 | 20 Feb 2025

Anastasiia Leonova is a publisher, art manager, curator, and co-founder of ist publishing based in Ukraine. Between 2014–20, she ran an independent art gallery in Kharkiv focused on contemporary art. With a background in Sociology and Art History, she specialises in photography and photobooks. Leonova is the curator of Mystetska Biblioteka, a project promoting contemporary artistic editions, and runs The Naked Books, a Kyiv-based shop dedicated to artistic books. She founded BOOK CHAMPIONS WEEKEND, a festival for photobook publishers, in 2021, and served on the jury for the 2023 Dummy Book Award.

What is your process for arriving at decisions about books and the projects that you undertake?

At ist publishing, we approach each book not just as a physical object but as the heart of a larger conversation. Publishing is a long-term journey – a process that extends into exhibitions, presentations, book signings, and the dialogues these encounters spark. To make this journey meaningful, we prioritise collaboration with artists whose practices we’ve followed over time. This allows us to build mutual trust, ensuring that both the artist and the publisher are aligned upon navigating the unpredictable yet rewarding path of book-making.

But book publishing is never just about aesthetics or storytelling. The decision to publish is often driven by urgency – political, social and cultural. Right now, in Ukraine, this urgency is sharpened by the context of war. Many of our projects focus on war-related topics, both in artistic and theoretical realms. These themes are not just relevant, but crucial. They help us process and accept our collective and individual experiences, offering a lens through which we can confront the realities of our time.

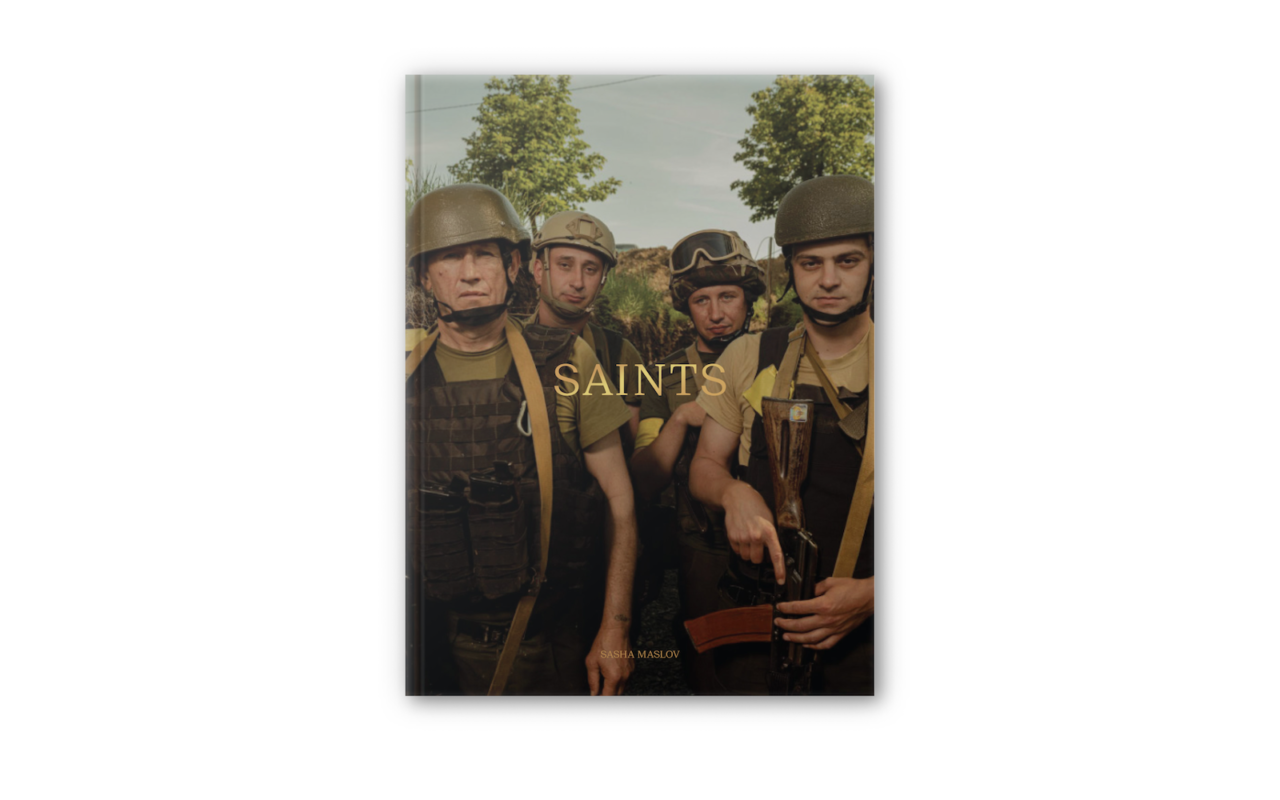

Take, for example, works that highlight resilience, embody a sense of mission, or contribute to the ongoing narrative of nation-building during times of profound upheaval. Saints (2024) by Sasha Maslov is one such book. This photobook shares the profound personal sacrifices made by Ukrainians during the Russian invasion of 2022–23. Through over 100 photographs and stories, Maslov portrays soldiers in the Armed Forces, volunteers and civilians whose everyday efforts contribute to Ukraine’s defence efforts. It is a work that speaks to the essence of modern sanctity – a concept redefined by the selflessness and resilience of ordinary people during the decade-long war.

Before 2022, we primarily focused on artistic projects and rarely worked with documentary photography. But nowadays, timing has become everything. With Saints, it felt like an urgent need to tell these stories to the world. We produced this 320-page book in a record four months, working through relentless shelling and constant power outages. The result was nothing short of extraordinary, with more than 2,000 copies pre-sold before going to print. In peaceful times, I could never have imagined such a scenario, but this experience demonstrated the power of photobooks as more than just artistic representation. They are also a vital tool for information, a means of communicating urgent, real-world narratives that demand to be heard.

Of course, we’d be remiss not to acknowledge the financial realities that shape this work. The cost of producing photobooks has risen sharply, and securing funding is more difficult than ever. Selling them presents its own challenges – photobooks exist in a niche market with high prices, where distributors often take more than half the revenue. At times, it feels like photobook publishing will remain the domain of the truly devoted. And yes, we proudly count ourselves amongst them.

Still, commercial considerations inevitably play a role. If an artist has a grant, a partner institution willing to support the project or a dedicated audience eager to purchase the book, it naturally becomes a higher priority. These partnerships and opportunities enable us to keep the doors open for projects that might otherwise remain unrealised.

For us, every book we publish is a commitment – not just to the artist, but to the audience and the questions that define our moment. Whether it’s a local story in Ukraine or a conversation about war, memory and identity, our goal is to create books that transcend their pages, sparking the kind of engagement that can reshape how we see and understand the world.

How do you like to work with people?

For each book we create, we assemble a unique team of translators, editors, designers and printers tailored to the specific project and its demands. Every publication has its own vision and challenges, and we believe the right collaboration is key to bringing it to life. That said, we also have a trusted pool of professionals – people whose work we’ve relied on for years and who understand our ethos.

As a publisher, I’m fully immersed in art direction. From the careful selection of works and the crafting of sequences to overseeing the precision of printing proofs, I ensure that every detail aligns with the vision of the book. When it comes to photobooks, the collaboration between designer and artist is particularly crucial. The designer must not only have technical expertise but also a deep connection to the artist’s work and a sensitivity to its nuances. This relationship often involves close teamwork under tight conditions, requiring trust, open communication and a shared creative language. Our process is deeply collaborative, with every book serving as the culmination of many perspectives and efforts, creating something both meaningful and enduring.

How do you balance choices between working with highly specific materials or processes, and the desire for access?

When an artist approaches us to create a book together, I believe they come with certain expectations – of quality, care and the level of visibility we’ve built through our previous projects. It’s a trust we take seriously, and we strive to maintain that standard with every publication.

However, delivering on that promise is a nuanced challenge. On one hand, we’re deeply committed to honouring the artist’s vision, ensuring the book reflects their expectations and creative intentions. On the other, we must navigate the realities of the book market. This means making the work accessible – both in terms of pricing and presentation – to the audience that has trusted us for years.

It’s a delicate balance, blending artistic ambition with practical considerations. The goal is always the same: to create a book that not only stands as a testament to the artist’s work but also finds its place in the hands of readers who will appreciate and connect with it. The challenge is what makes it rewarding – crafting something that resonates on multiple levels, staying true to our ethos whilst continuously adapting to an ever-changing landscape.

What is the public for a photobook? Who do you think of as your audience?

Photobooks have long existed in a niche space – a specialised audience of other photographers, publishers, collectors, enthusiasts, and art-world professionals who gather at book fairs, enter contests and celebrate their craft in awards. This ecosystem is vibrant, but it is also insular. The question we constantly grapple with is how to expand this audience, to bring photobooks out of the art bubble and into the hands of a broader public. And should we really expand it?

Last year, this question took on a new urgency when we were approached by Ukraine’s largest electricity provider, which supplies 90% of the country’s power. After suffering catastrophic losses to infrastructure during the brutal winter of 2022–23 – when Russian missile strikes and shelling damaged countless energy facilities and left millions in the dark – they wanted to create something remarkable.

At first glance, this collaboration seemed unusual. What does a power company have to do with photobooks? Yet, for us, it was a natural fit. We drew on our extensive network of photographers, many of whom risked their lives to document the fallout of this energy crisis. The resulting book is a powerful visual story of resilience, featuring work by more than 30 Ukrainian photographers. It is a tribute to those who refused to give up – engineers and electricians who worked tirelessly to ensure that darkness didn’t prevail.

For me, this project was, in a certain way, a revelation. It proved that photobooks can transcend their origins. They can become tools of storytelling and education, reaching audiences far beyond the art world. Making photobooks more accessible is not just an artistic challenge but a communicative one. By bridging the gap between the photobook community and the broader book market, we can amplify their impact. Photobooks may have started in a niche, but they don’t have to remain there. It’s not just about expanding the audience, but expanding the possibilities of what a photobook can be.

How important is it for photobooks to reach other continents?

Photobooks, by their very nature, present invaluable opportunities for cross-cultural learning. The ability to make such works accessible worldwide reinforces their significance – not just for the communities they originate from, but for the global conversation they can enrich. When shared with a wider audience, even the most specific stories begin to reveal their connections to shared human experiences, transforming them into universal reflections.

Often, projects like the ones we work on in Ukraine focus on deeply local topics, yet they hold universal relevance when viewed through a global context. Take, for instance, our latest photobook, The Chips: Ukrainian Naїve Mosaics of the 1950–90s (2024), by Yevgen Nikiforov and Polina Baitsym. This work documents the fragile beauty of mosaics created by unknown authors – a vanishing phenomenon in public art and memory. Although these mosaics are specific to Ukraine, the theme resonates far beyond the country’s borders, echoing the preservation challenges faced by similar public art forms in the UK, Mexico and India.

At ist publishing, our efforts extend beyond photobooks. We are deeply committed to translating and publishing texts in philosophy, anthropology, architecture and other culturally relevant fields. By bringing thinkers such as W.G. Sebald, Rem Koolhaas, Anna Tsing, John Berger, and Susan Sontag into the Ukrainian context, we aim to bridge intellectual gaps that often leave us isolated from the broader international dialogue. Like any book, a photobook is fundamentally an act of communication – an exchange across geographies and cultures. It is a way to address the distances that separate us whilst uncovering shared dilemmas we all face, even if our engagement with those dilemmas differs.

What makes this effort so compelling is the recognition that photobook publishers from all corners of the globe face strikingly similar challenges in the photobook market. Rising production costs, small audiences and the precarious nature of distribution are universal obstacles. However, these shared difficulties highlight the vitality of the photobook as a medium. The struggle to preserve and disseminate these unique cultural artifacts is not an isolated endeavour but part of a broader global effort to connect, communicate and understand one another in ways that transcend language, borders and time.

The global network of publishers, artists and readers, each grappling with similar questions and concerns, becomes a testament to the enduring power of the book as a shared cultural venture. Bringing a photobook to another continent is not merely about extending its reach, but itself act of profound understanding.

What is the place of language and writing in a book of photographs?

Language is a bridge, a foundation for communication that connects the visual and the textual, offering context, meaning and dialogue. For me, it is a vital part of any book.

In Ukraine, the role of language has become even more charged during Russia’s full-scale invasion. For decades, our society existed in a bilingual state, a cultural legacy of imperial influence (roughly half of Ukrainians spoke Russian, whilst the other half spoke Ukrainian). There was something beautiful about this coexistence – friends sitting at the same table, speaking in two languages without even switching, effortlessly blending them in a way that fostered mutual understanding.

But the war changes everything. Many of us came to realise that speaking Russian was not entirely their choice but a legacy of imposed dominance, a remnant of cultural erasure carefully engineered over centuries. This realisation sparked a nationwide shift, an intentional decision to reclaim Ukrainian as a language of daily life, resistance and identity.

At first, it was difficult. Language isn’t just about grammar; it’s deeply personal. It carries memories, habits and intimacy. For many, the transition was most challenging with loved ones, where a shared vocabulary of affection – specific words, familiar intonations – had been forged in Russian. But with time, speaking Ukrainian has become second nature, a habit that carried weight and meaning, a step toward preserving and nourishing something truly ours.

In our photobooks, this relationship with language finds expression through a dual-language approach. Each book speaks in Ukrainian, honouring its local roots, and in English, opening its narrative to the world. This balance feels right: it respects the images, the stories they tell and the audiences who will hold these books in their hands.

Who have been the models or templates for your own activities?

The guiding lights of my work are many, each offering something invaluable. Loose Joints inspires with their bold, fresh selection of projects, daring to venture where others might hesitate. Spector Books captivates with its exceptional design, turning every page into a tactile experience that enhances the narrative. Images Vevey stands out for their thoughtful and caring collaboration with artists, creating a space where creativity thrives in mutual respect. Jason Eskenazi’s wisdom on photo sequencing has been a treasure, teaching me that the order of images is as powerful as the images themselves. Antoine D’Agata, with his boundless enthusiasm for creating new books and reinvigorating the methods of presenting work, continually pushes me to think beyond conventional boundaries. And, of course, all of our authors, who, through each project, show me how to look deeper, to resist rushing toward conclusions, and to embrace the raw truth of the story without unnecessary interpretations.

What would make a better photobook ecosystem?

A better photobook ecosystem is one that addresses the economic challenges and distribution hurdles faced by publishers, artists and readers alike. The photobook, as an art form and a medium of storytelling, thrives in a specialised ecosystem, but to grow and become more accessible, we need to rethink how it is produced, sold and shared across the globe.

One of the most pressing issues in the photobook world is financial sustainability. The production of photobooks, particularly those that involve high-quality printing, binding, and design, is expensive. As costs continue to rise – driven by inflation, the increasing price of materials and labour shortages – many small publishers are forced to make difficult decisions about the number of copies they can print or the price they must charge. This creates a barrier to entry for new publishers, limits the variety of voices in the market, and, in some cases, forces publishers to choose between maintaining artistic integrity and ensuring the financial viability of a project.

To address this, publishers, artists and distributors need to build more collaborative financial models. This could involve pooling resources for shared production costs, offering crowd-funding opportunities for specific projects, or working with larger institutions – such as museums, galleries or cultural organisations – that can help fund photobook projects whilst offering wider visibility. It is also important to reconsider how photobooks are priced. Whilst they are often considered niche objects, pricing should strike a balance between making them accessible to a broader audience and supporting the value of the artist’s work. Special editions, smaller print runs and flexible pricing models can help achieve this.

Distribution is equally important in creating a more vibrant photobook ecosystem. Currently, photobooks are primarily sold through limited markets – specialised bookstores, art galleries, photography fairs, and direct sales from publishers. These platforms are vital, but they limit the reach of photobooks to a relatively small audience. To truly expand the photobook’s influence, it needs to be integrated into larger book markets, accessible in mainstream bookstores, and available through online retail platforms where a broader audience can discover them.

However, as I said, the move towards mainstream distribution must not come at the cost of artistic integrity or the community that has sustained photobooks for decades. The challenge is finding a way to expand their reach without diluting their cultural and artistic value. For this, hybrid distribution models should be explored, by partnering with online platforms or larger book retailers whilst also maintaining the intimacy of smaller, independent channels where the spirit of the photobook community thrives.

An often overlooked but critical aspect of a stronger photobook ecosystem is the need for effective marketing and promotion. Photobooks often rely on a niche audience that already understands the value of the medium. However, to grow this audience, publishers need to develop strategies that can introduce the medium to a wider public.

Lastly, a robust, transparent distribution network that ensures the availability of photobooks at multiple price points and in diverse regions is necessary. Working with distributors who understand the unique nature of photobooks and can support their presence in non-traditional retail environments (like pop-up shops, festivals and temporary exhibitions) is key to growing the ecosystem. By building more collaborative and accessible financial structures, expanding distribution beyond niche markets and investing in the promotion and education of new audiences, we can create a more sustainable and vibrant future for photobooks that is both economically viable and artistically enriching.♦

Further interviews in the Photobook Conversations series can be read here

Click here to order your copy of the book

Images:

1-Anastasiia Leonova © Igor Chekachkov

2-Sasha Maslov, Saints (ist publishing, 2024)

3-Katya Lesiv, I Love You (ist publishing, 2021)

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique and activism

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous Dahmani

• Shana Lopes reviews Agnieszka Sosnowska’s För

• Valentina Abenavoli discusses photobooks and community

• Michael Grieve considers Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler’s posthumous collaboration with their late family member

• Elisa Medde on Taysir Batniji’s images of glitched video calls from Gaza