Metabolising violence: interview with J.A. Young

We speak with the winner of the OD Photo Prize 2025, J.A. Young, who turns to an ongoing body of work wrought from trauma, research and experiments in the darkroom. Between lived experience and occult inquiry, the series, Angels considers how violence, control and intuition inscribe themselves into the materiality of hand-made prints, and what it might mean to summon images from forces that, though invisible, are anything but absent.

Thomas King | Interview | 25 Sept 2025

Join us on Patreon

Thomas King: Can you tell us about the point of departure for Angels, recently announced as the winner of OD Photo Prize 2025? How did the research first take form and what impulse or circumstances set it in motion? And what do you wish to conjure in your choice of title?

J.A. Young: My first series, Of Fire, Far Shining (2023-24), was a collection of prints I made almost entirely on a cheap laser printer. But I knew that I eventually wanted to move into hand making each print, and I was finally able to begin that process in late 2024 after getting the space to set up my current darkroom. Angels (2024-) is exclusively composed of silver gelatin prints that I’ve created over the past year, and in part, the change in series marks this shift toward a more alchemical printing process that results in unique material objects.

My research has always been one of the primary drivers of my creative process, and it remains a consistent source of inspiration from series to series. But it’s not necessarily the source of the new title. Like any other creative urge, a word or phrase will just flash into my mind, and I will immediately recognise it as one of my titles. It then becomes a defining element of the series, in that it’s the only predetermined concept that I’m intentionally bringing with me into the creative process. By holding the title loosely in the back of my mind, I can play with all the associations it evokes.

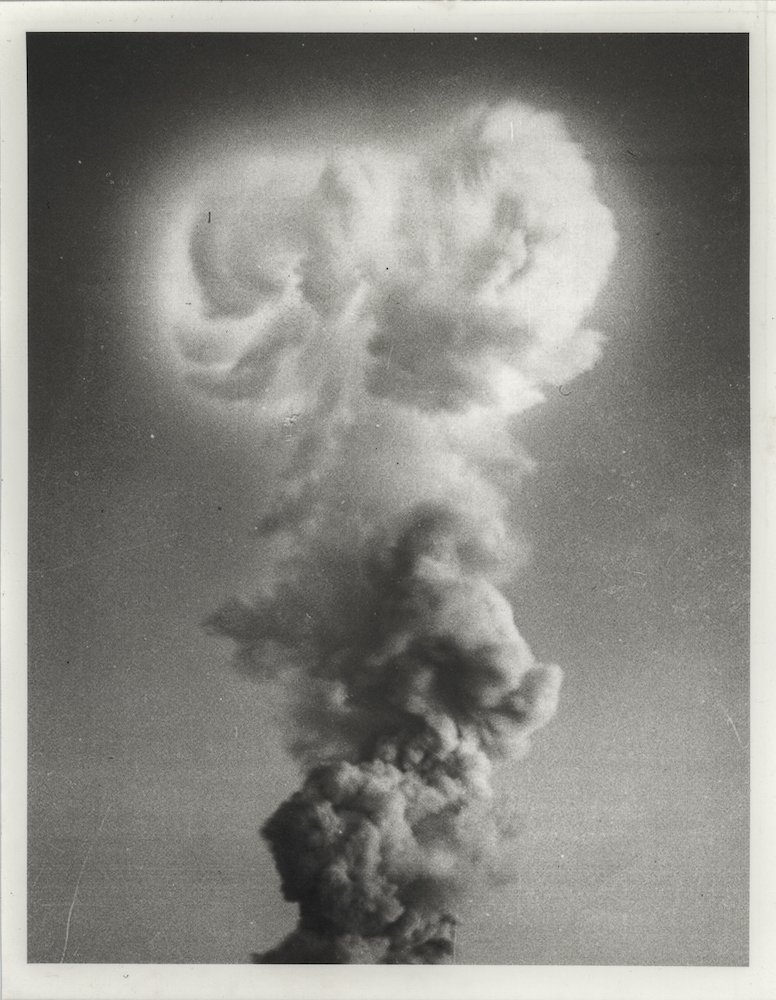

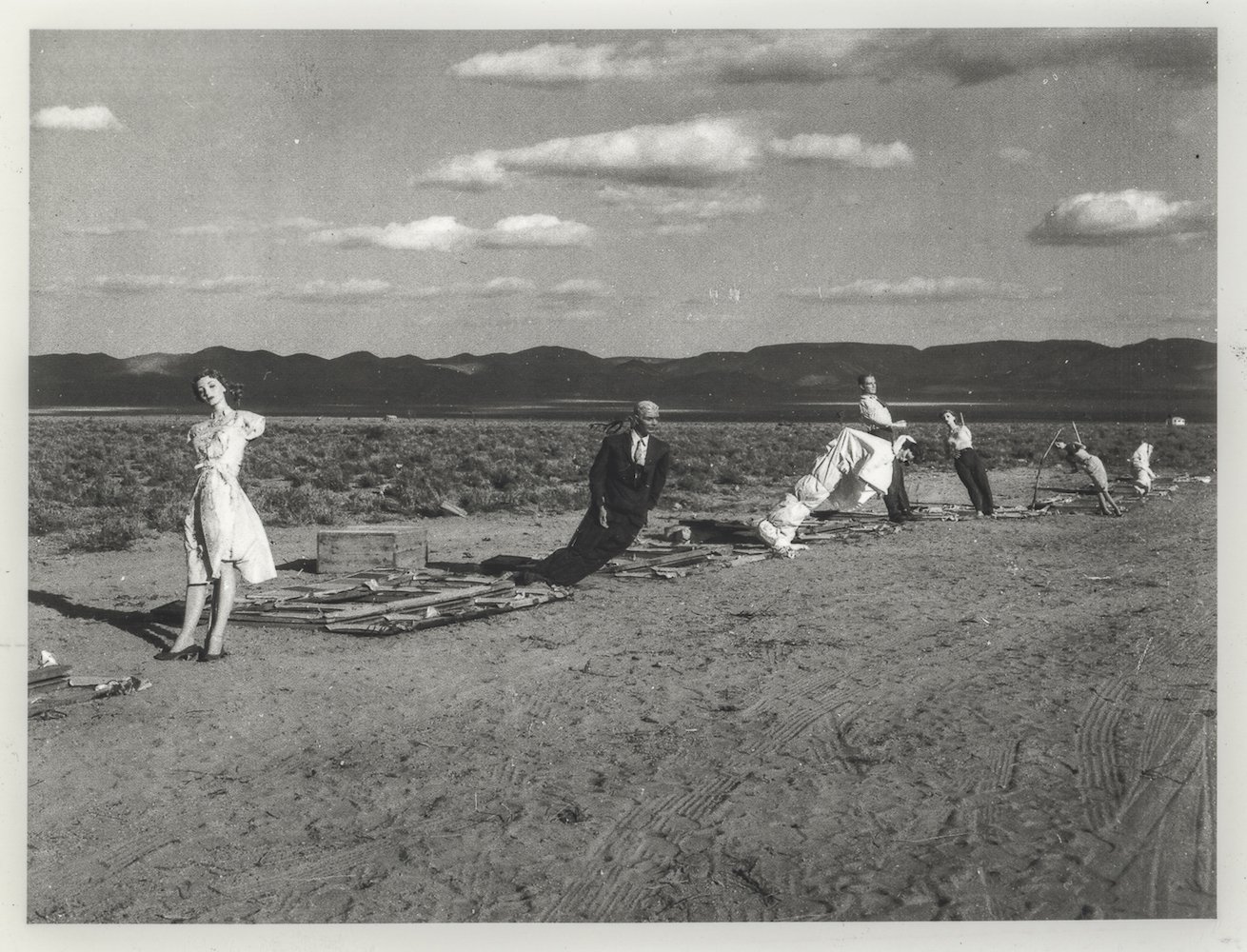

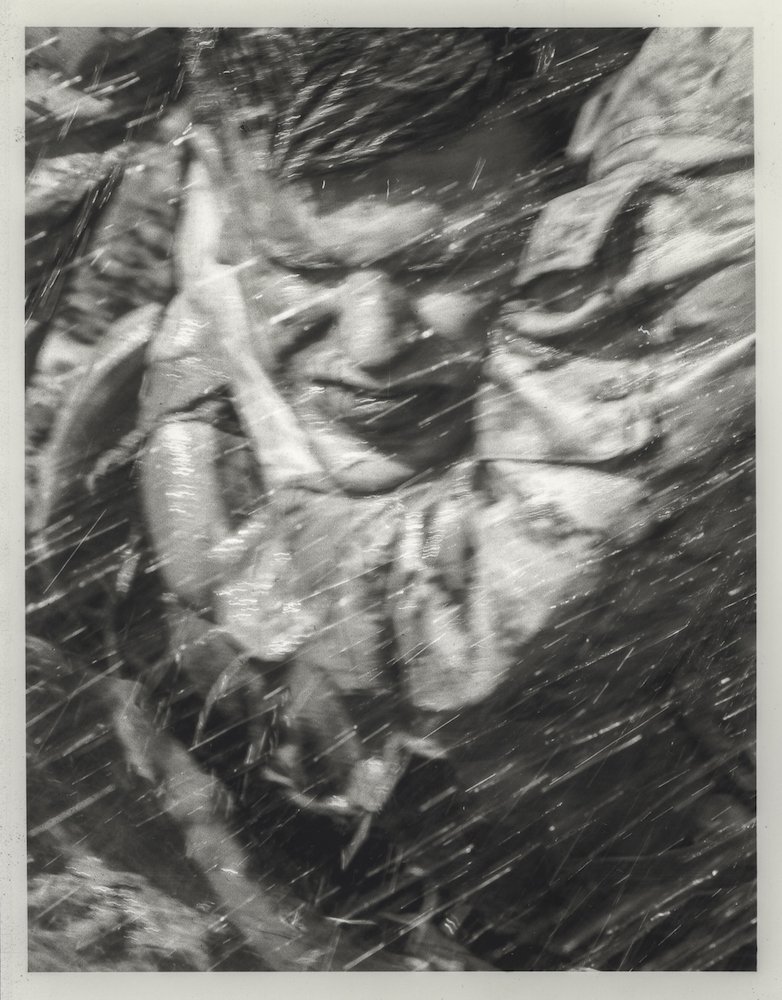

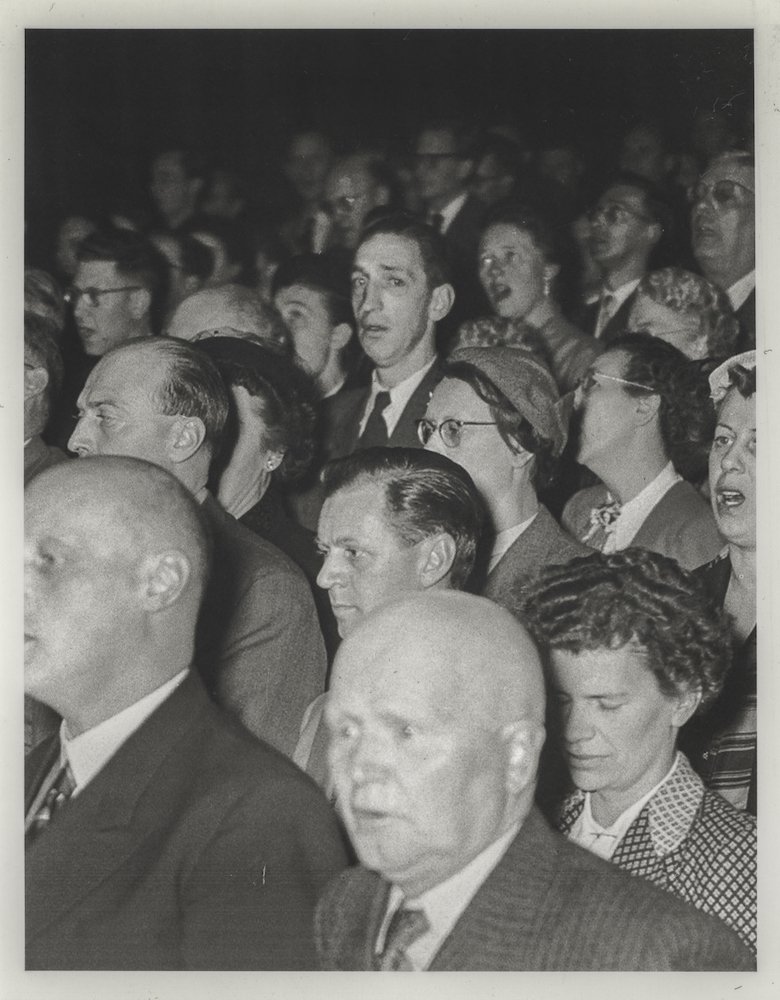

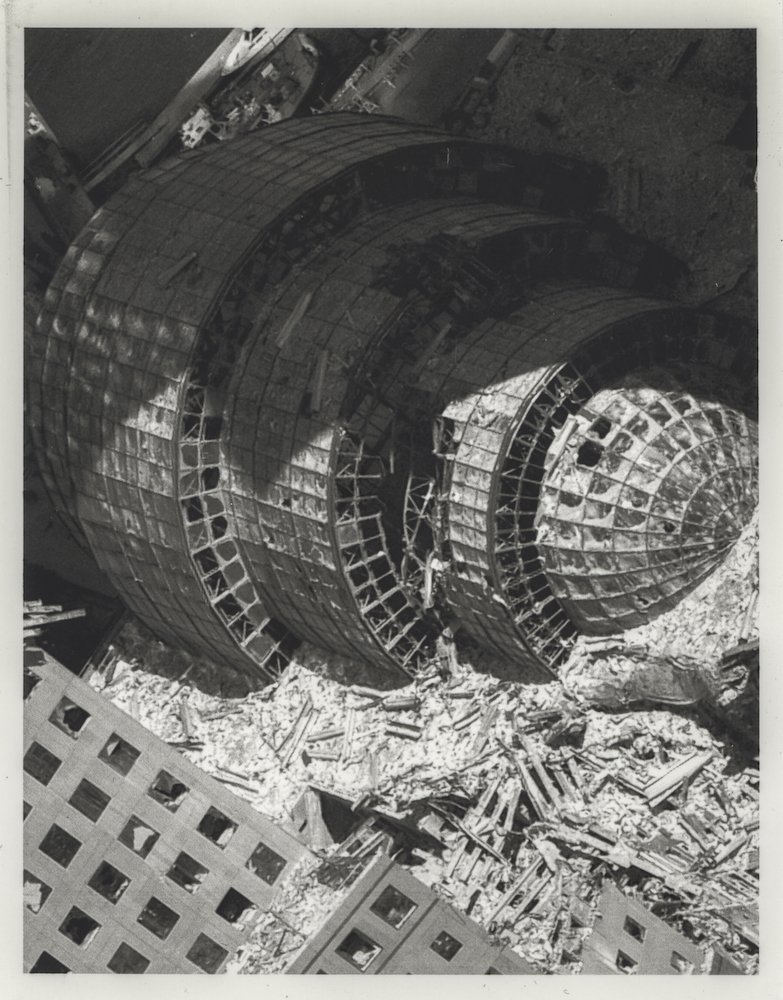

The angels that I’ve had in mind while making the series aren’t benevolent figures of light; they’re more like the Archons of the Gnostics or the Vedic Asuras, ethereal beings that use their power to oppress and deceive. In the images I’m creating, I’m essentially positioning modern institutions as these very angels: vast, impersonal systems of control that function with a logic that is both overwhelmingly powerful and entirely indifferent to the suffering they inflict. These are the archetypes of control, judgement and power, now embodied by algorithms, corporate monopolies and the military industrial complex. So what you see playing out across the series is the visible impact of these invisible forces.

TK: You’ve said that your work draws on lived experience, on inhabiting a world not quite one’s own. How do questions, or perhaps disturbances, of selfhood root themselves in Angels? In what ways do they contour or complicate the work?

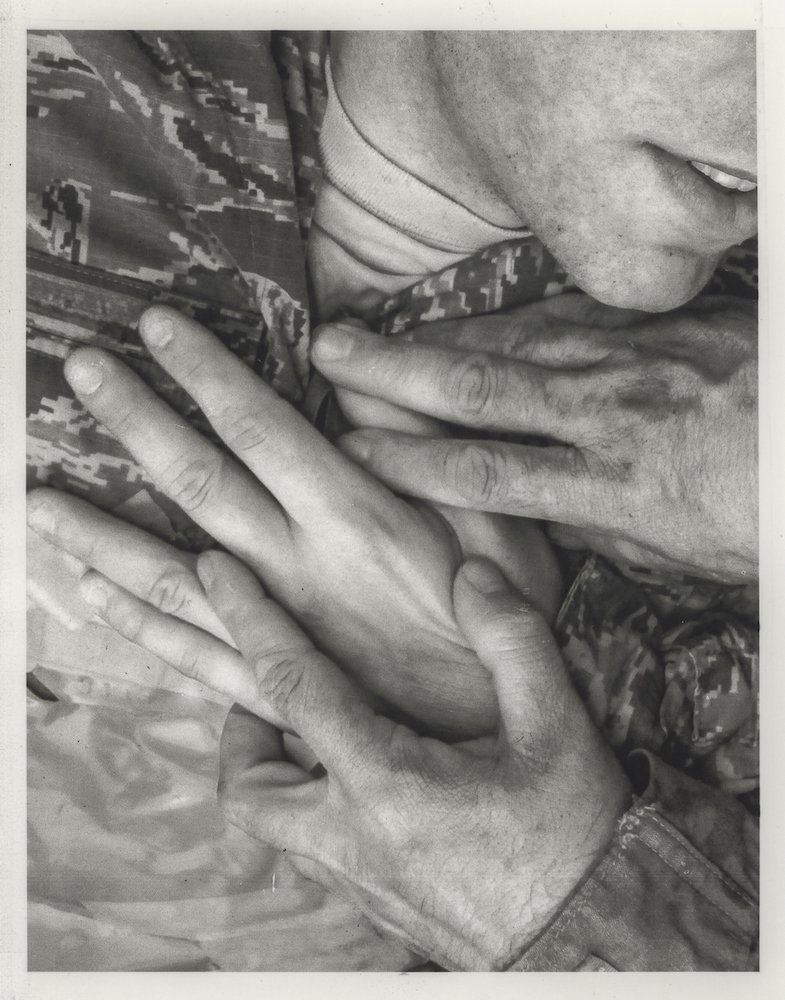

J.A.: I’ve experienced a lot of trauma in my life, and it’s made me feel very unsafe and very isolated in the world. A lot of violence has been inflicted on me, and most of it has been in response to core facets of my identity, like the fact that I’m trans and neurodivergent, among other things. This has altered how I view being in the world and human history in general, and that shows up in the atmosphere of my images. Beyond that, I can see in my images my own feelings of claustrophobia and of desperation about the all the tragedies and crises we’re facing: it’s like everything is constantly in motion; everything is speeding up; everything is swirling around us as we barrel towards so many terrible consequences of our actions.

My spiritual experiences and my research into the occult are also directly related to how I make my art. When I work, I’m trying to open myself up completely, to allow my unconscious to move through me, and to trust that process, to trust this other part of me to which I don’t normally have access, to do the work. So it feels like I’m surrendering to my intuition and letting my body act and react to the materials that I’m using, and that itself feels like a magical process. I feel the safest I’ve felt in my life when I’m making art in this way. I feel like I’m finally allowing the emotions I’ve held in my body to bubble up, and then somehow, when I make a piece of art that holds some of those feelings, it’s as if I’ve captured it and released it from my body.

TK: What are the visual sources for the images you use as foundational material? Could you expand on the process of transformation through which your multi-layered pieces come together, and the implications for the original image? How do these material encounters take shape, constrain or release the work’s possibilities?

J.A.: I use both my own negatives and images sourced from public domain digital archives as raw materials for transformation.

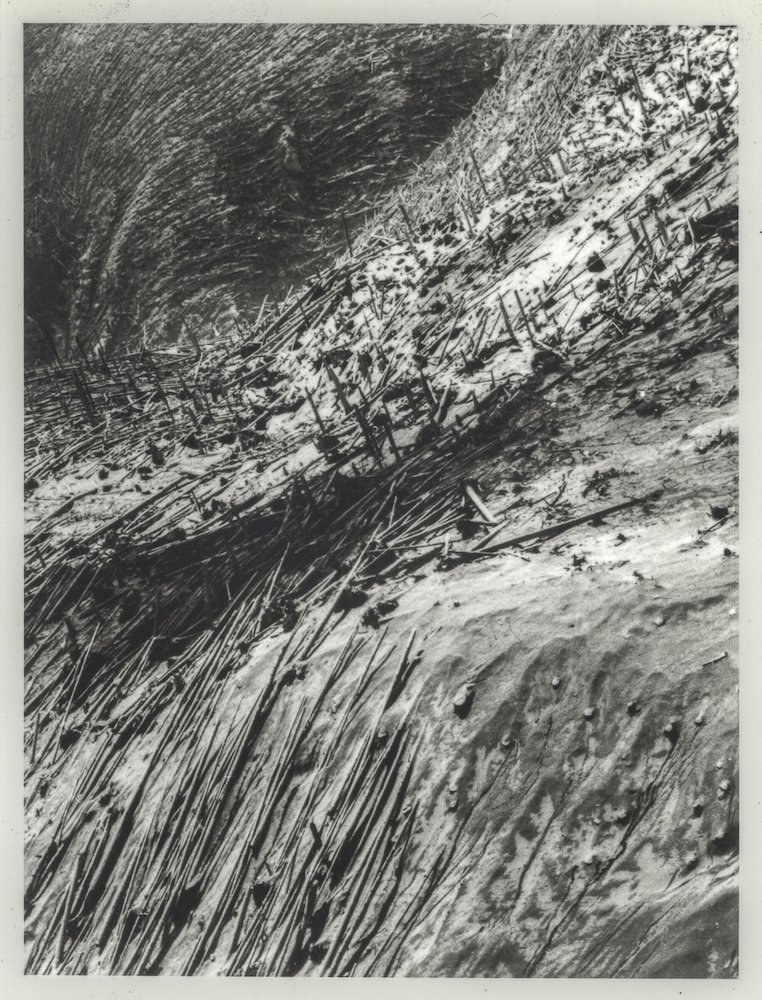

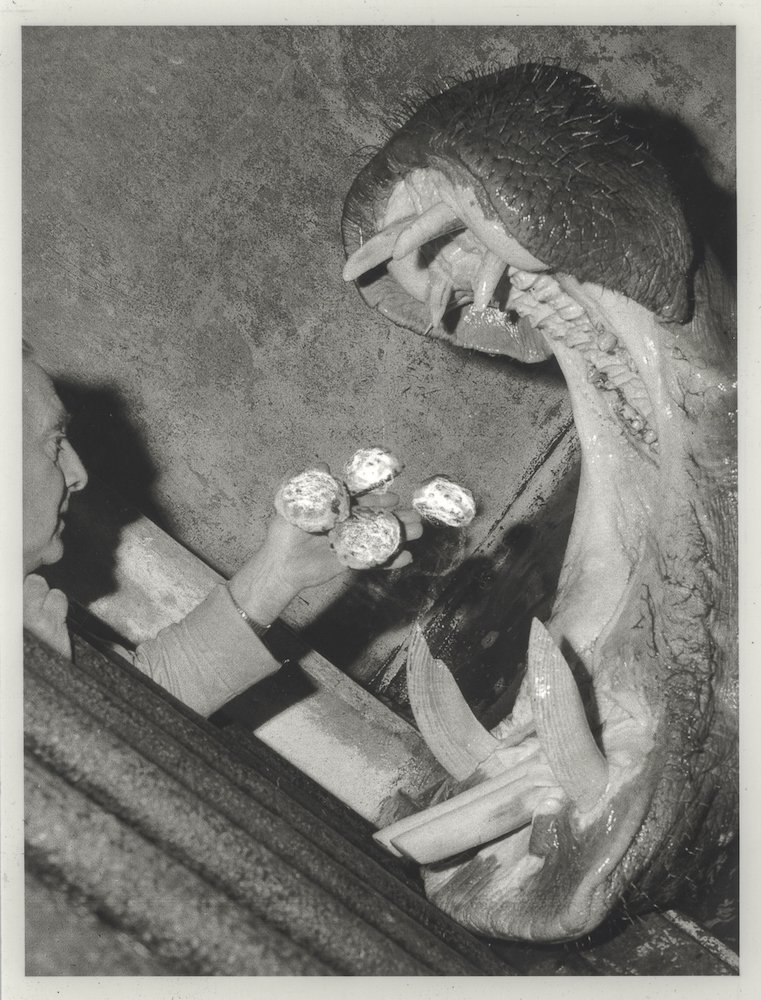

The first, most important, and most radical step in my alteration of the source material is creating a new composition. I deconstruct and throw away most of the image until I arrive at a very specific composition that’s often just a small detail from the original. It feels sculptural in this sense, in that I’m removing more and more of the raw material until I arrive at an object I’m satisfied with. And every single element in every composition that I make is intentional: every detail in every corner, the tonal range in the image, the textures, the shapes, the lines, everything. It’s not that I plan it ahead of time, but I know how I want it to feel, and I keep reworking it until it clicks into place. The content of the source material itself doesn’t dictate what I end up with; it’s insufficient on its own, and if I can’t create a composition that pleases me, I throw it away.

The extent of what happens next will vary depending on the image. In my darkroom, I’m experimenting with different emulsions and paper substrates, with exposure, with time, with temperature, with the chemicals I use and how I use them. After that, I might physically alter the print or rephotograph and reprocess it in some way – whatever it takes to get to the specific qualities I’m looking for. Again, I don’t plan any of the decisions I’m going to make ahead of time. It’s a process of trial and error that’s being guided by gut feelings. Either it feels right or it doesn’t.

TK: The subjects which you frame or focus on in Angels often intimate and depict violence… Are you constructing this series with a pre-visualised sense of narrative, a deliberate mapping of feeling and effect, or does it emerge more intuitively?

J.A.: My process is fundamentally intuitive and iterative. When I’m working, I’m completely absorbed in and devoted to the specific image in front of me. I’m not thinking about a broader, pre-visualised narrative. Instead, I’m following a non-verbal, often visceral pull, judging each creative decision by the way it feels in my body. It’s a process of feeling my way toward a very specific resonance. I’ve cultivated a deep trust in this somatic guidance; a trust that if I can make each individual piece as emotionally and psychically ‘correct’ as I can, the larger narrative coherence of the series will emerge organically on its own.

When I do step back to look at several finished prints together, the recurring elements of violence don’t surprise me. While the process is intuitive, my intuition isn’t drawing from a void. It’s tapping into a well filled with a lifetime of experience and research. Because I’ve experienced a significant amount of physical and systemic violence, that trauma is stored in my body, and my art is one of the primary ways I access and metabolise it. At the same time, my research is focused on the large-scale violence of state and corporate power. In the work, I’m essentially transposing my personal, embodied experience of harm onto this macro scale.

Ultimately, I’m not trying to predetermine the content of an image, but I am trying to embed a specific feeling. I might want to create a sense of paranoia or disorientation, for example, and I will manipulate the materials until that feeling is present. I think of each piece as a tiny, emotionally charged fragment of a much larger event that is constantly unfolding. If the fragment is charged correctly, it will hopefully activate something in the viewer, and they can fill in the blanks in the narrative.

TK: Since you began this project in 2024, we increasingly find ourselves in a political landscape where mythologies are bound up in a war of images and modern society experiences an ever-growing sense of despair. What are your thoughts on the agitational relationship between photography and historiography?

J.A.: When it comes to my own art, many of the raw materials I start with are benign archival or personal photographs that don’t have any direct connection to the sociopolitical and environmental themes I’m exploring in my work. But, by reframing them in a specific way, decontextualising them, altering them, and placing them within the landscape of my series, I can give them a radically different emotional charge.

On the other hand, when I’m using raw materials that are directly connected to the themes I’m exploring (e.g., archival photographs that document a specific nuclear weapons test), I’m also deliberately removing the context, so that their meaning isn’t bound up in a single event. And I think that lack of context makes the experience of my images more confrontational and more immediate.

Many of the images I source from government archives were designed as propaganda, their basic function being to construct a state-approved reality; and part of the satisfaction I get out of altering them to the point of being unrecognisable is that I’m undoing their intended results. Being able to manipulate images in this way has given me a visceral understanding of the way that images can be used to penetrate into peoples’ subconscious and to elicit emotions and ideas about all kinds of things. I think this is a beautiful function for art, in that it allows for the possibility of a very deep connection between the work and the viewer. But in the hands of the institutions I’m critiquing, it’s weaponry, deployed on a mass scale.

TK: What’s next for Angels?

J.A.: Right now, I’m continuing to experiment in my darkroom, and I’m interested in taking more control of the physical materials themselves, for example, by hand-coating various substrates with liquid silver gelatin emulsion. I’m also exploring new ways to physically deconstruct and deteriorate the prints after they’re made.

Looking forward, I plan to incorporate additional mediums, like moving images and sound. And in the more immediate future, I’m excited to be working with OD Gallery, who will be making a selection of limited edition prints from the series available.

Angels is very much a living, expanding body of work, so my primary focus is to continue building its world.♦

All images courtesy the artist and Open Doors Gallery. © J.A. Young

—

J.A. Young is an experimental mixed media artist and photographer based in the American South. In 2025, she was selected as a Fresh Eyes x Hungry Eye Talent Award Winner, and her debut solo monograph was shortlisted for Les Rencontres d’Arles Author Book Award.

Thomas King is Editorial Assistant at 1000 Words and currently undertaking an MA in Literary Studies (Critical Theory) at Goldsmiths, University of London.

Images:

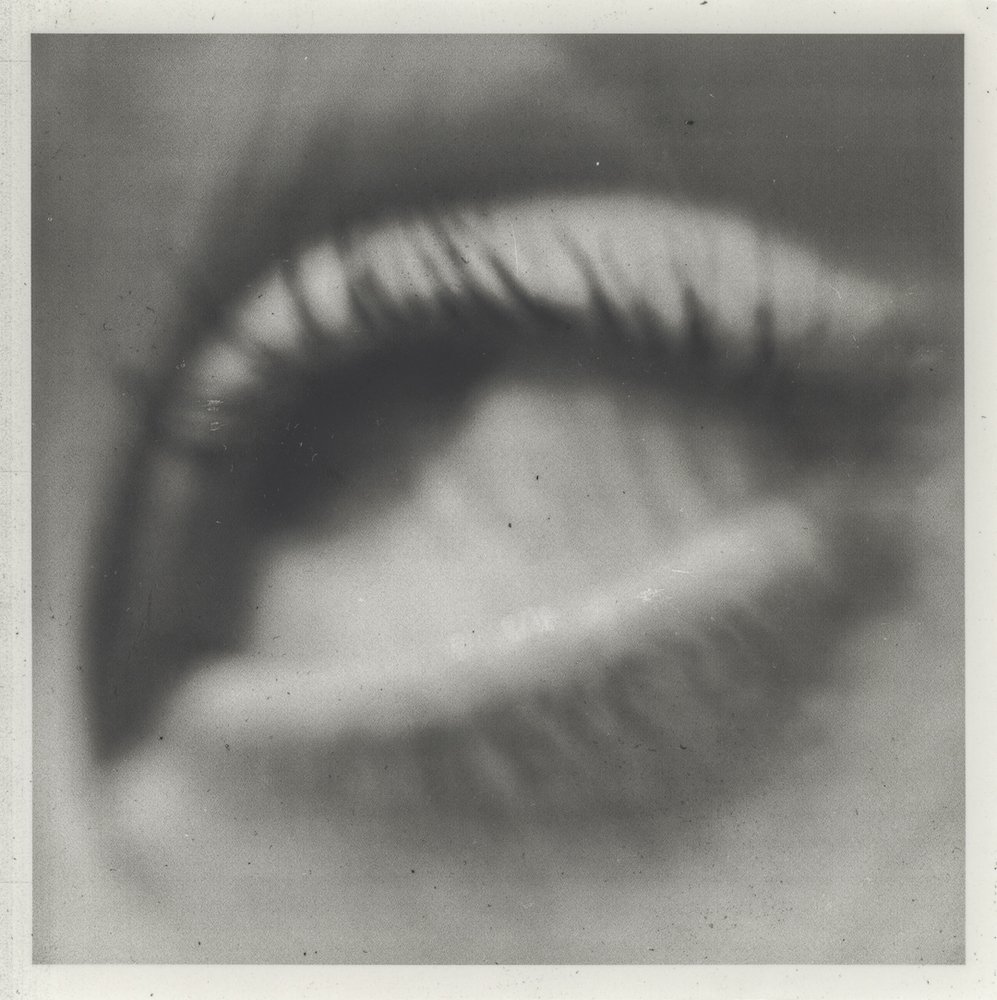

1-J.A. Young, Angels no. 7, 2025

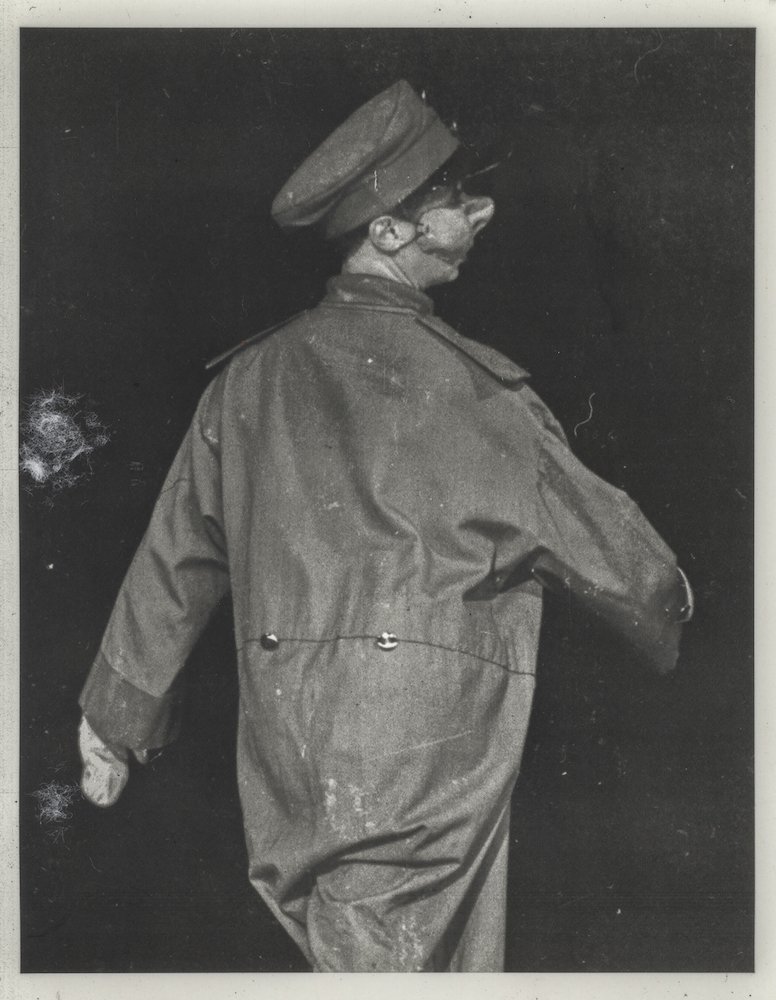

2-J.A. Young, Angels no. 8, 2025

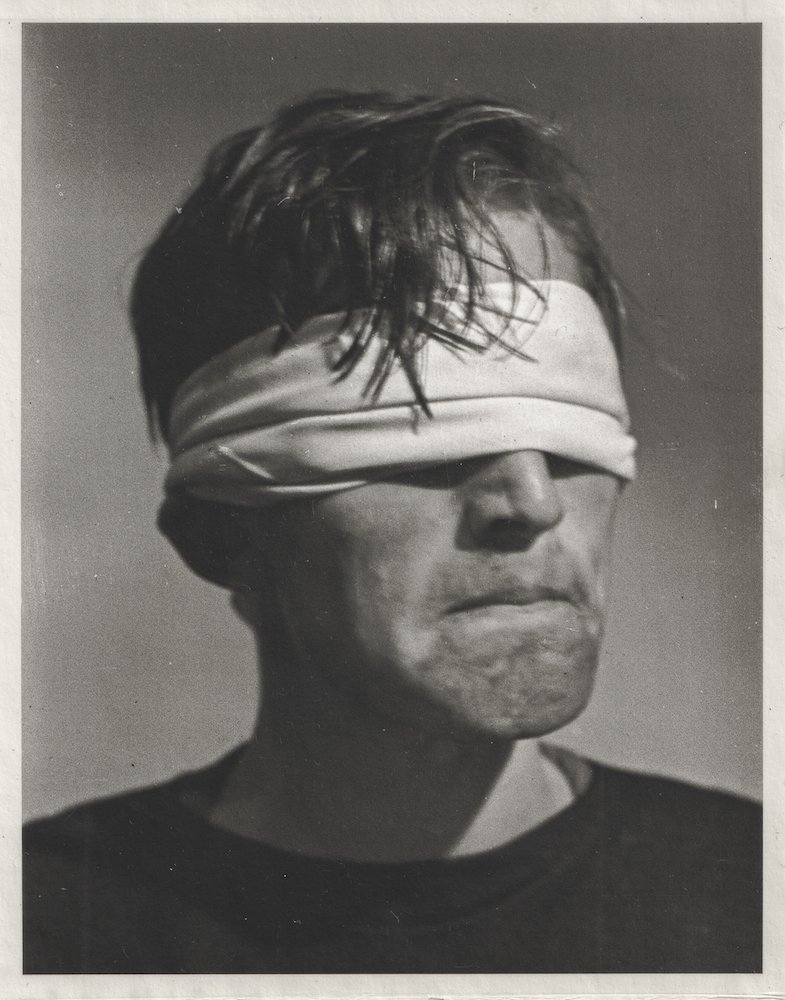

3-J.A. Young, Angels no. 11, 2025

4-J.A. Young, Angels no. 34, 2025

5-J.A. Young, Angels no. 56, 2025

6-J.A. Young, Angels no. 66, 2025

7-J.A. Young, Angels no. 81, 2025

8-J.A. Young, Angels no. 86, 2025

9-J.A. Young, Angels no. 89, 2025

10-J.A. Young, Angels no. 95, 2025

11-J.A. Young, Angels no. 110, 2025

12-J.A. Young, Angels no. 138, 2025

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique and activism

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous Dahmani

• Shana Lopes reviews Agnieszka Sosnowska’s För

• Valentina Abenavoli discusses photobooks and community

• Michael Grieve considers Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler’s posthumous collaboration with their late family member

• Elisa Medde on Taysir Batniji’s images of glitched video calls from Gaza

Join us on Patreon today and be part of shaping the future of photographic discourse