Arles 2025: staging radicality within safe limits?

Is the art world willing to take real political risks, or does it perform radicality within safe limits? What to make of aesthetic gestures of dissent without institutional accountability and without any attempts at broader movement building? Peter Watkins probes these questions and more in the context of Les Rencontres d’Arles 2025, arguing that a familiar absence remains despite this year’s theme of ‘disobedient’ images. Elsewhere, festival highlights include Nan Goldin’s recurring interventions, intergenerational collaboration between Carol Newhouse and Carmen Winant, a guerilla poster campaign by NO-PHOTO, and the deeply personal work of Diana Markosian.

Peter Watkins | Festival report | 24 July 2025

Join us on Patreon

The notion that images and their makers can be ‘disobedient’ implies that they hold the power to disrupt, to rebel and to resist the status quo. It suggests that they might serve as an outlet towards a more progressive politics – a means of confronting and reflecting on the systems of power that shape both cultural and political life, and a means to propose critical and aesthetic alternatives in response to the world around us.

In this moment of collective urgency, when the systems that govern us are becoming increasingly repressive and authoritarian, the idea of disobedience takes on an increased importance and risk. The current climate in Europe and the United States is marked by the widespread institutional cancellations of artists, slashing of cultural budgets, silencing of academics and student protests, increased state violence, and the suppression of free and open political and creative expression. Against the rise of “nationalism, nihilism and environmental crises,” as the festival put it in their opening gambit, we might do well to ask how seriously Les Rencontres d’Arles takes the artistic and political freedoms of those presented in this year’s edition, and address what has been left unsaid in the process.

In a statement issued during the 2022 edition, Les Rencontres d’Arles declared its unilateral support for the Ukrainian people in their “fight for freedom,” dedicating the opening week to honouring the “artists and photographers whose lives are threatened by Russia’s aggression.” Fast forward three years, and while the war in Ukraine rages on, this year’s edition includes neither mention nor representation of Ukrainian artists, institutions or direct geopolitical issues related to the region.

While this year is marked by the inclusion of historically marginalised communities, issues surrounding colonial legacies and is notable for its work of inclusion and politics of representation, there remains a colossal elephant in the room. For a festival – and an industry – that has spent years championing diversity, flirting with decolonial discourse and sexual politics, the absence of any tangible mention of the political realities we find ourselves in the present is both deeply disappointing and troubling.

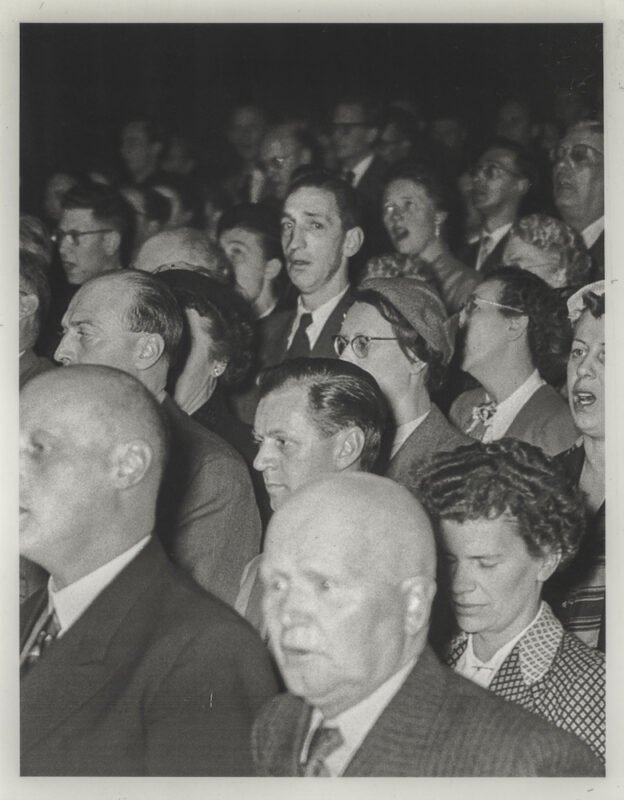

It was left to Nan Goldin, once again – leveraging her considerable artistic and cultural influence – to say what the festival would not. To kick off proceedings, her film Memory Lost (2019-21), underscored by answering machine recordings, seminal photographs of her and her friends, and revolving around abuse, friendship, love, deprivation, and loss, was accompanied by a live piano performance by Eliza McCarthy. It played out to the vast imposing Théâtre Romain, which was full to the brim with approximately 2500 people, comprising those from every corner of the photography community. Goldin was presented with the Women in Motion award, which she accepted graciously, joking that Les Rencontres had shown bravery in honouring her at such a politically charged moment, and promised the audience a surprise at the end.

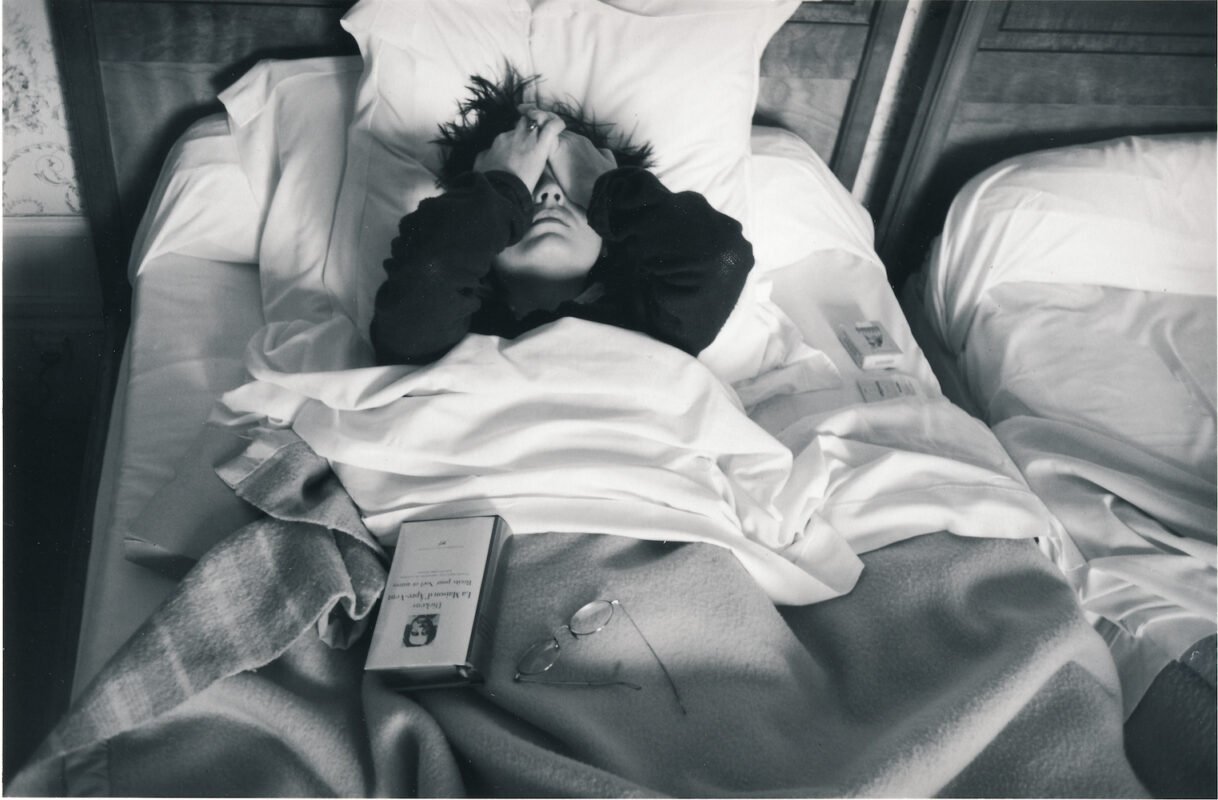

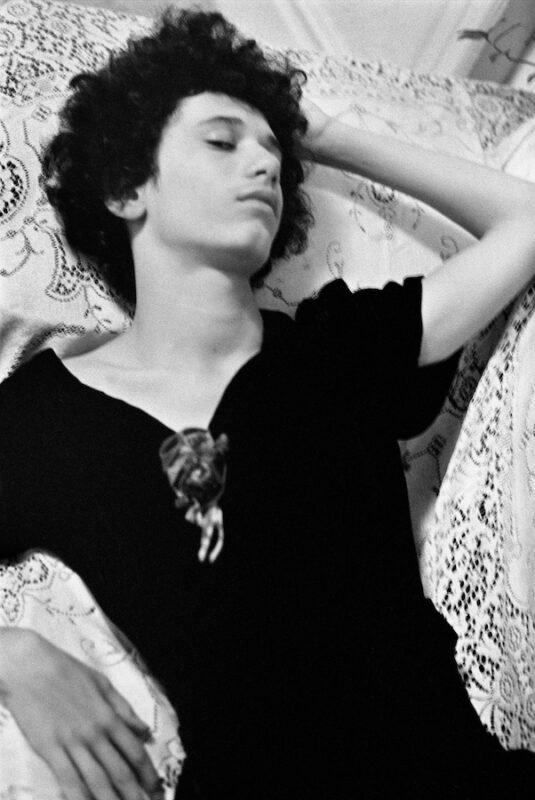

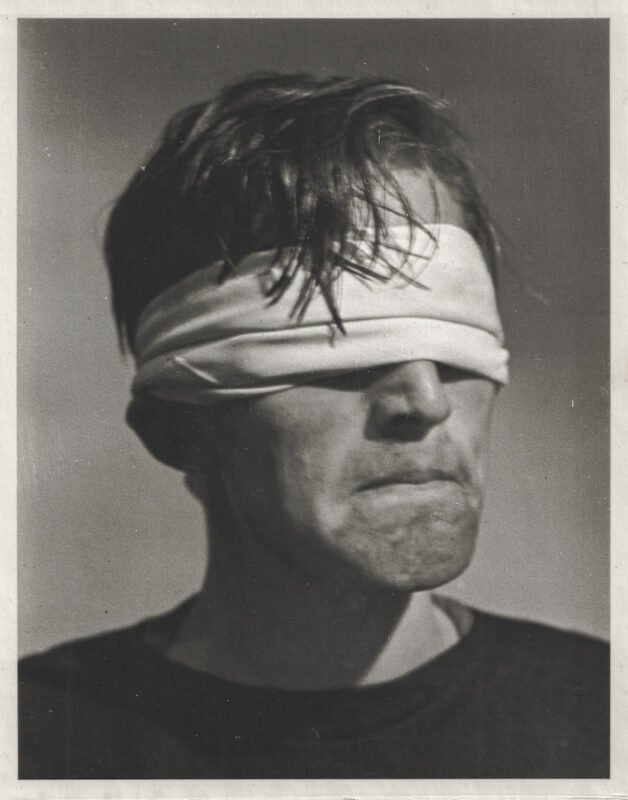

In the conversation that followed, she chose to speak out against the growing repression of trans and LGBTQIA+ communities, particularly in the context of increasingly draconian policies in the United States that have eroded decades of progress in terms of policy and rights. This was accompanied by a slideshow depicting her early photographs of drag queens, starting out with a portrait of David Armstrong depicted here as a young man dressed as a woman. “He wasn’t a queen himself,” she reflected, “he was just so androgynous and beautiful that men would divorce their wives when they saw him.”

As the moon shone brightly in the night sky, a spotlit Nan Goldin told the audience that “we need silence now.” The word Gaza appeared across the screen. The film was composed of video clips compiled from social media. It started like this: Children playing, laughing, bustling food markets, panoramas of cosmopolitan life. People congregating, families on the beach, kids flying kites, a birthday party, a father throwing his child into the air. Then, plumes of smoke, citizens evacuating, explosions, dead bodies, a man shaking uncontrollably with fear, people running, people dying, neighbourhoods reduced to rubble, dead journalists surrounded by living journalists, a man comforting a child. A child holding the head of a dead parent. And the unmistakable look of horror in the eyes of the children. Towards the end we see desperate unarmed Palestinians running for aid. A child no older than eight years old says: “we are tired of this darkness. We are tired of this life.”

The video was silent, there was no audio, but for the wind catching the giant projection screen. What followed was a powerful speech by Goldin standing alongside writer Edouard Louis who shared the burden. At 71 years old, Goldin struggled at some points to stand, but her voice remained steady and erudite. Some of the audience left in a steady stream, but most stayed, and when one woman heckled passionately screaming about hostages, the palpable tension that had filled the air bubbled over, with Goldin moving off script, and addressing the woman directly, but keeping her cool. Free Palestine chants rang out in solidarity and Goldin completed what she had come to say. When she returned to her seat near to where I was sitting, she said in typical Nan Goldin style: “get me outta here,” to her youthful entourage.

A wide range of UN bodies, the International Court of Justice, judicial panels, investigation committees as well as most major human rights NGO’s and experts, have characterised Israel’s military campaign in Gaza as Genocide, warning that it meets the criteria as defined by the Genocide Convention. More than 50,000 children have been killed or injured by one of the most sophisticated war machines on the planet. Food and aid is being used as a weapon of war. Genocide is occurring in Gaza, but also in Sudan, in Myanmar, in Congo. Our complicity in the West and in our industry is marked by the silence of our institutions, and the gatekeepers at their helms, prioritising corporate sponsorship above moral clarity.

Change can only occur through lifting this silence, practicing disobedience and risking something of ourselves in what we believe in. It should not have to fall squarely on the shoulders of Nan Goldin to be the mouthpiece for an industry’s failures. We speak of care, inclusivity, decolonialism and progress, yet this festival has been unable to acknowledge the horrors of the present moment, nor create any tangible platform for them to be discussed. We have a collective duty to do more, and we must do so much more.

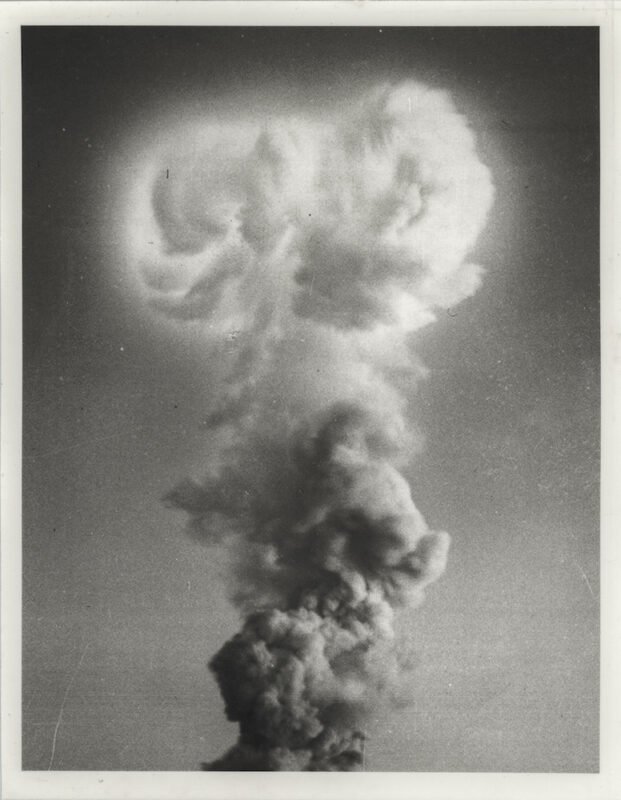

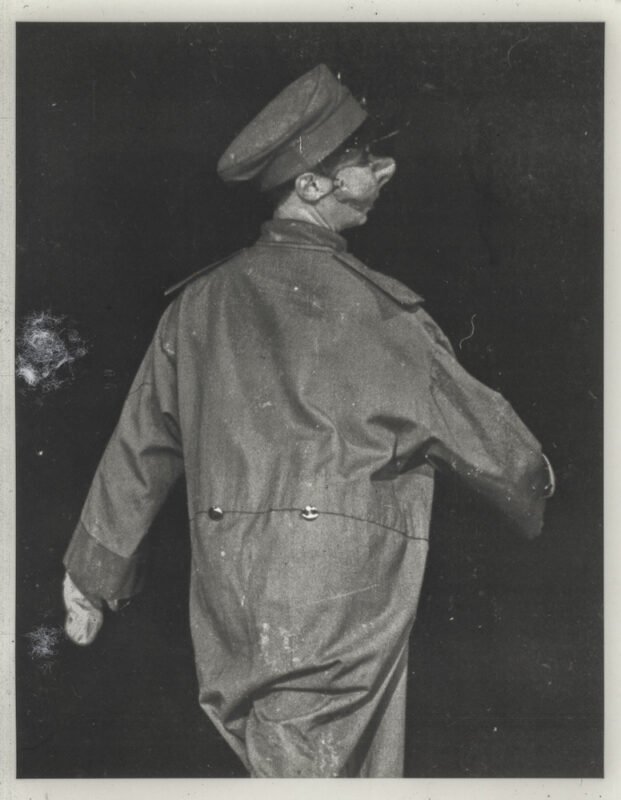

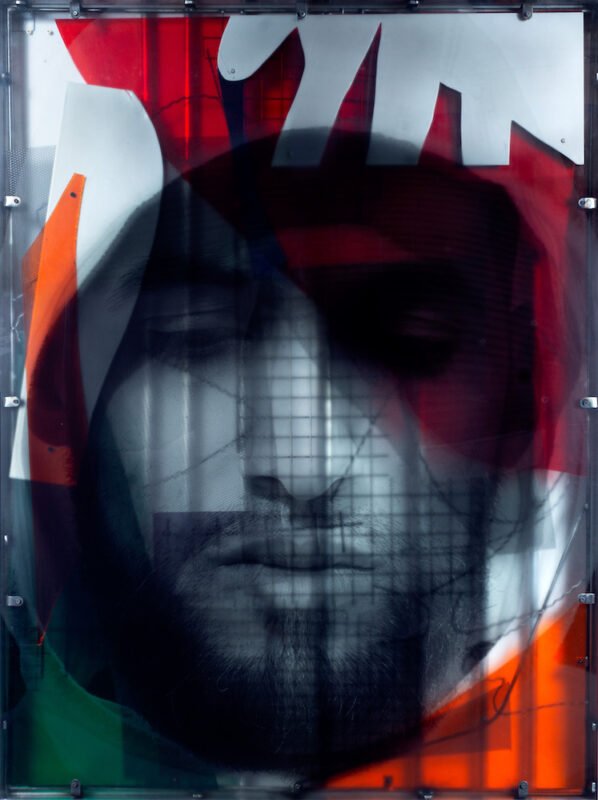

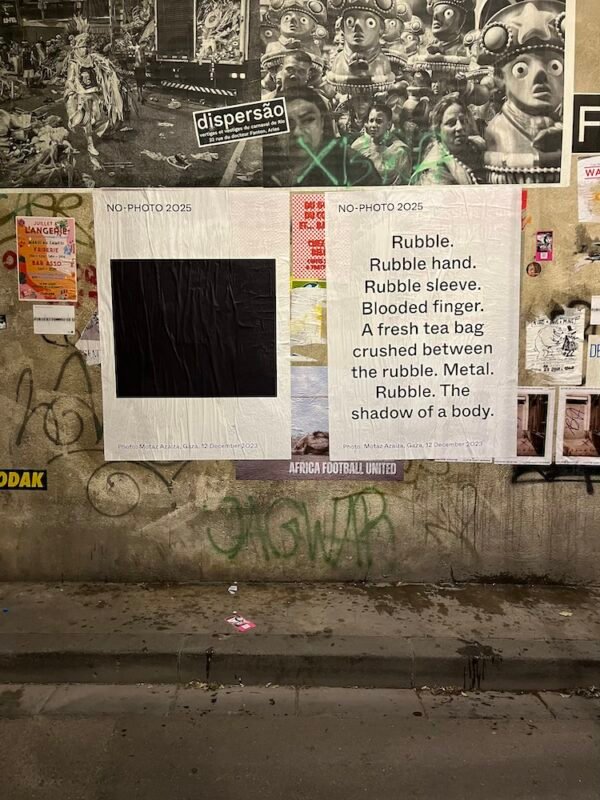

NO-PHOTO, a collective of artists and activists, were notable for their powerful campaign of posters plastered up on walls around Arles. Made up of textual descriptions of photographs from Gaza, the collective called for “cultural institutions to align their visual language with ethical clarity and action.” The power of these political works lies in their conceptual premise: a deliberate refusal to include photography. The image is replaced by a void, a black rectangle, representing a conscious rejection of resharing photographs of Palestinian suffering as tokens to evoke compassion, but rather referring back to the ubiquity of those images through their absence.

An accompanying newsprint featuring an essay from 2023 by Ariella Aïsha Azoulay argues that genocide cannot be captured in a single image, but must be traced across a body of images and actions over time. It asserts that Israel is a settler colonial regime built on the systematic displacement and elimination of Palestinians, using strategies such as expulsion, incarceration and militarised control, especially in Gaza. She talks about how the normalisation of Palestinian suffering through images frames their lives as disposable. She concludes by stating that we must acknowledge this genocide, our complicity, not only for the sake of the Palestinian cause, but for the sake of humanity, pluralism and justice.

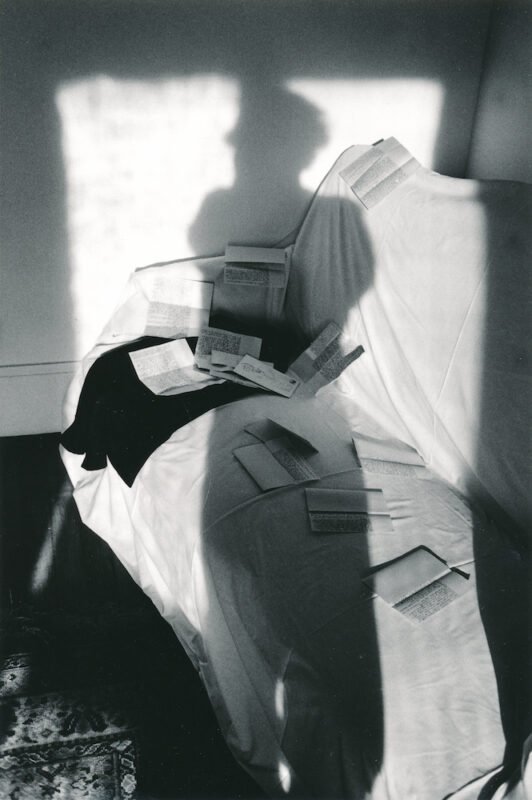

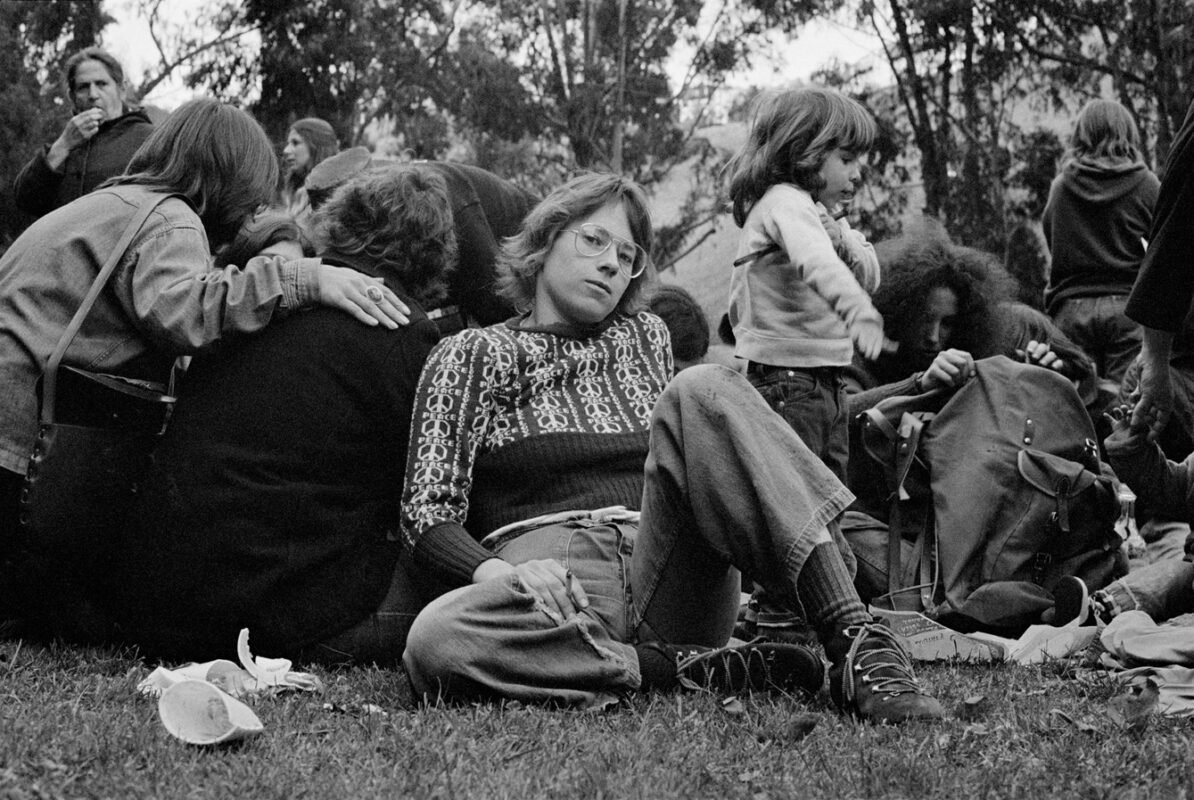

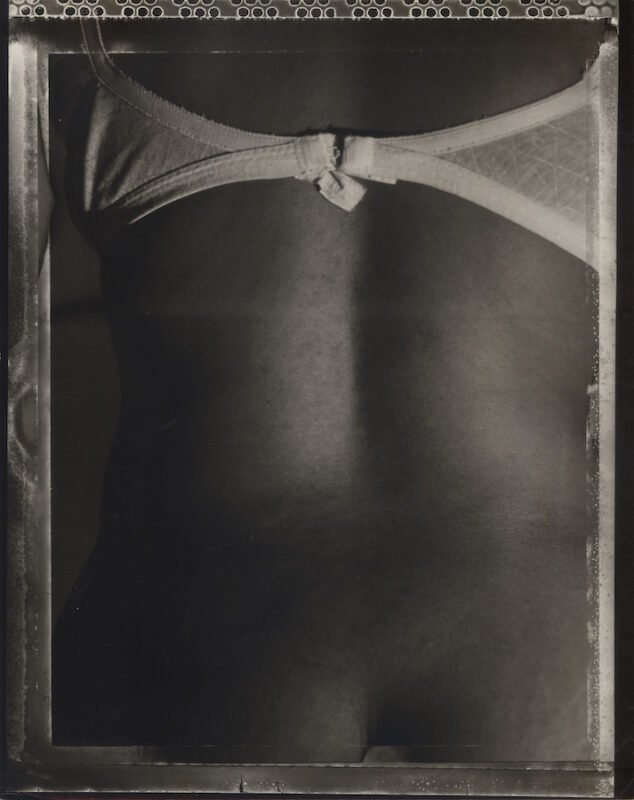

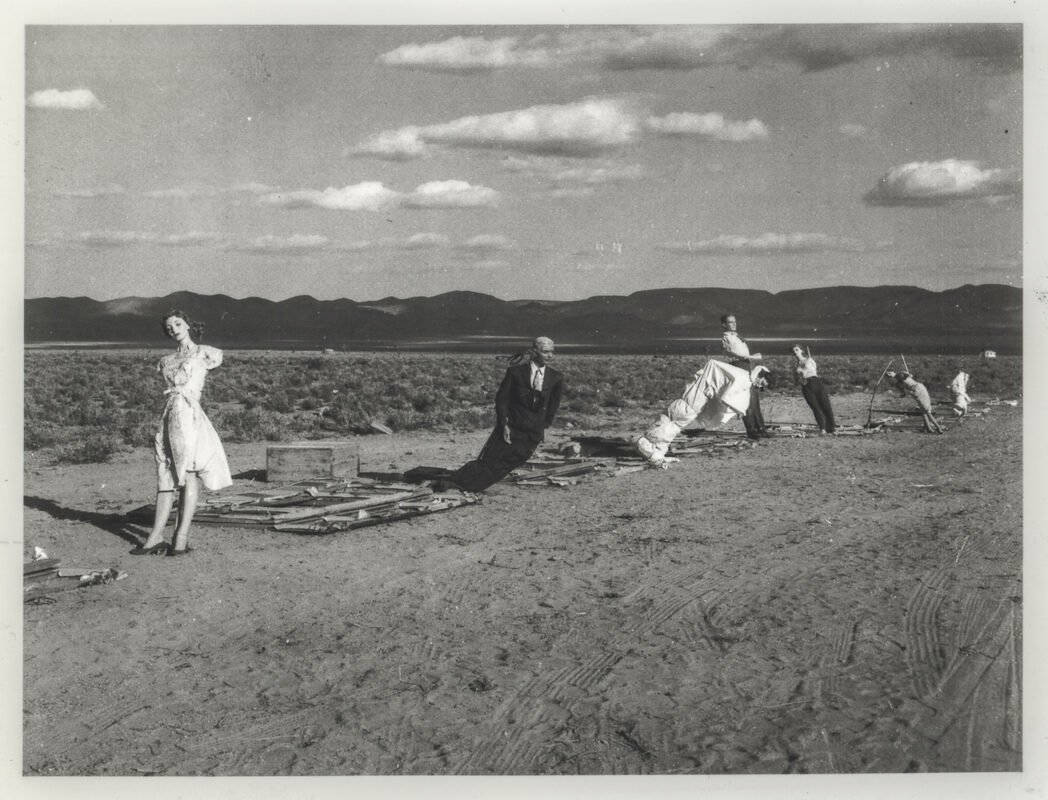

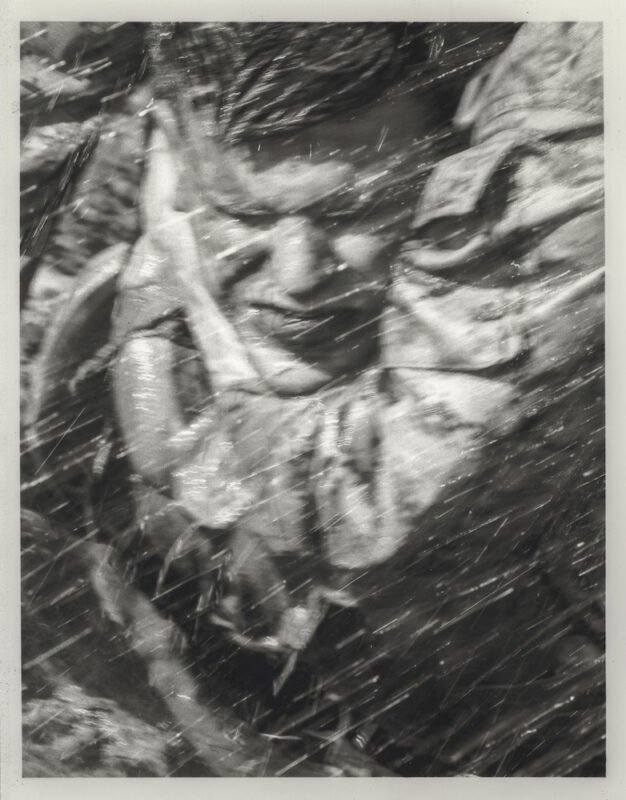

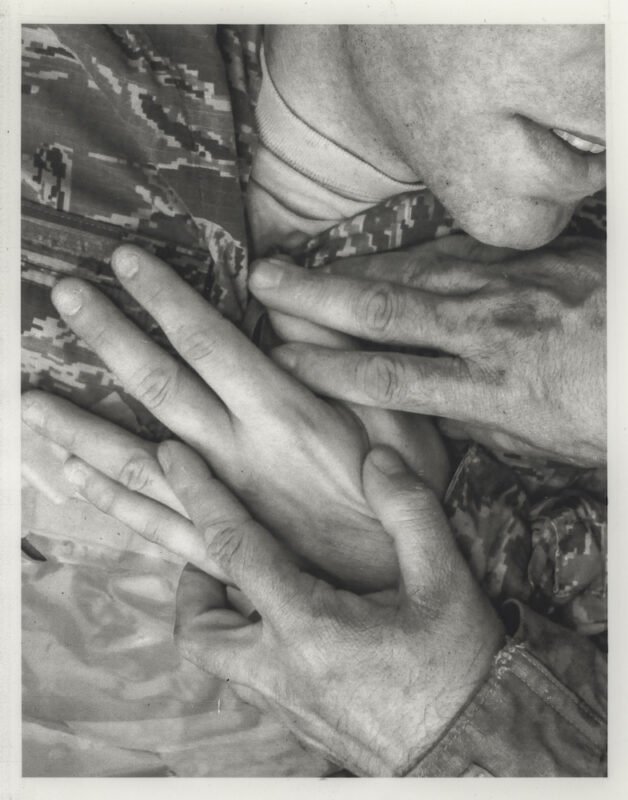

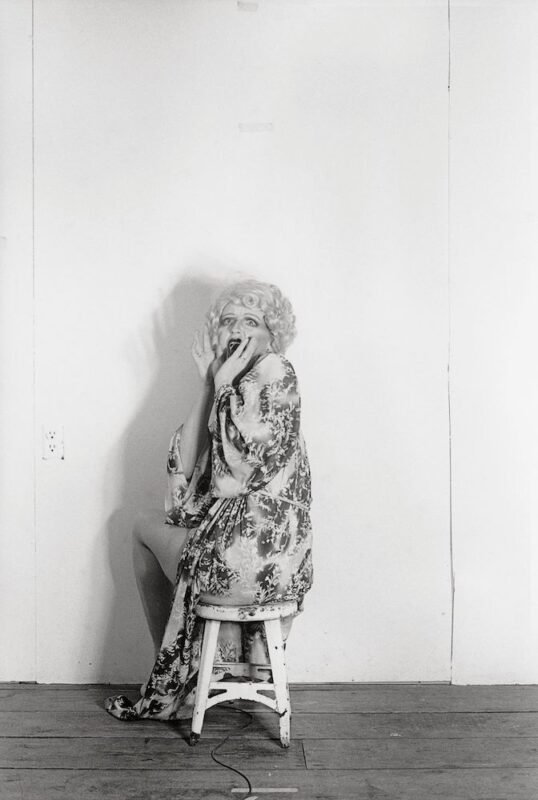

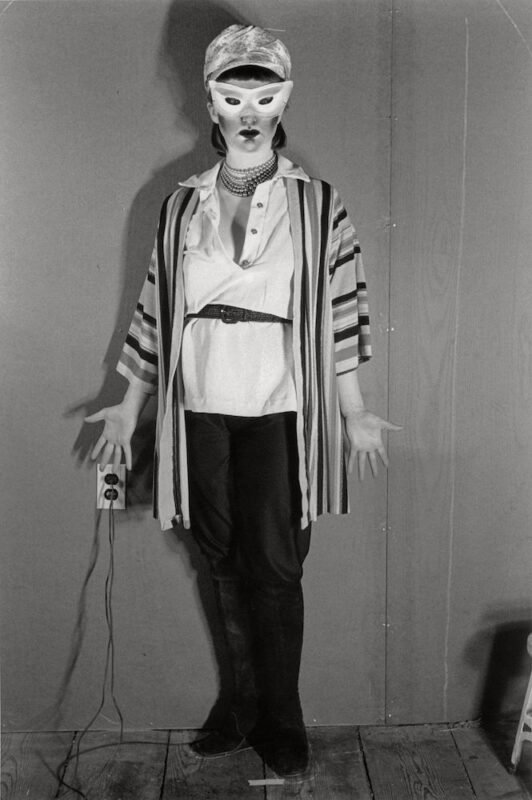

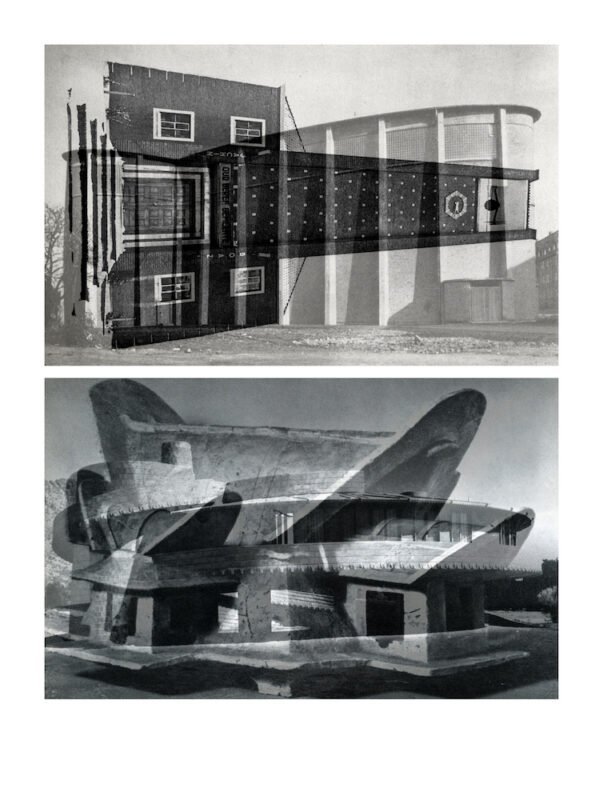

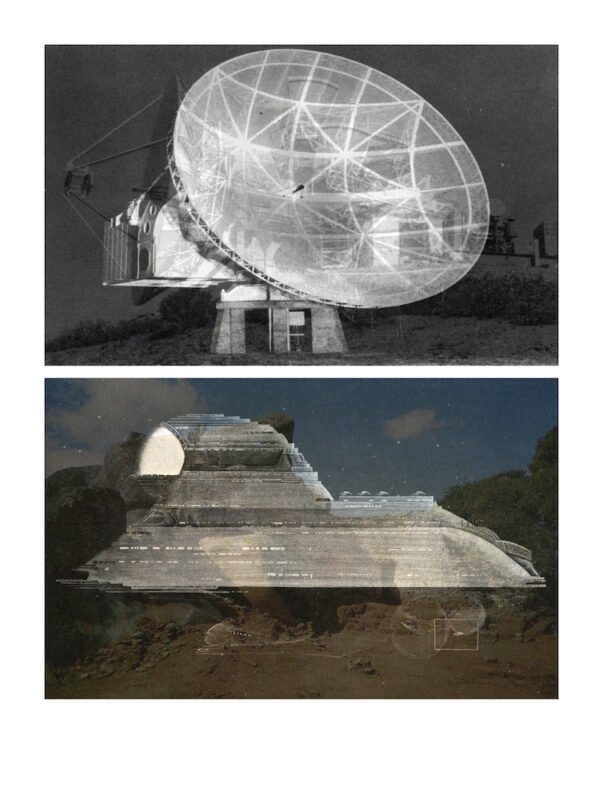

Carole Newhouse and Carmen Winant’s collaborative exhibition simply titled Double was quietly one of the highlights of the festival. Thoughtful, tender, their collaboration marks an intergenerational feminist alliance which looks to reclaim and amplify feminist strategies from the past and bring them to the present. Through the simple gesture of double-exposure, the two women collaborated on a series of works that were an aesthetic pleasure to behold. The exhibition invites us to consider the transformative potential of a radical reinvention and reclamation of the self. Neatly curated by Nina Strand, it is well executed, intelligent work.

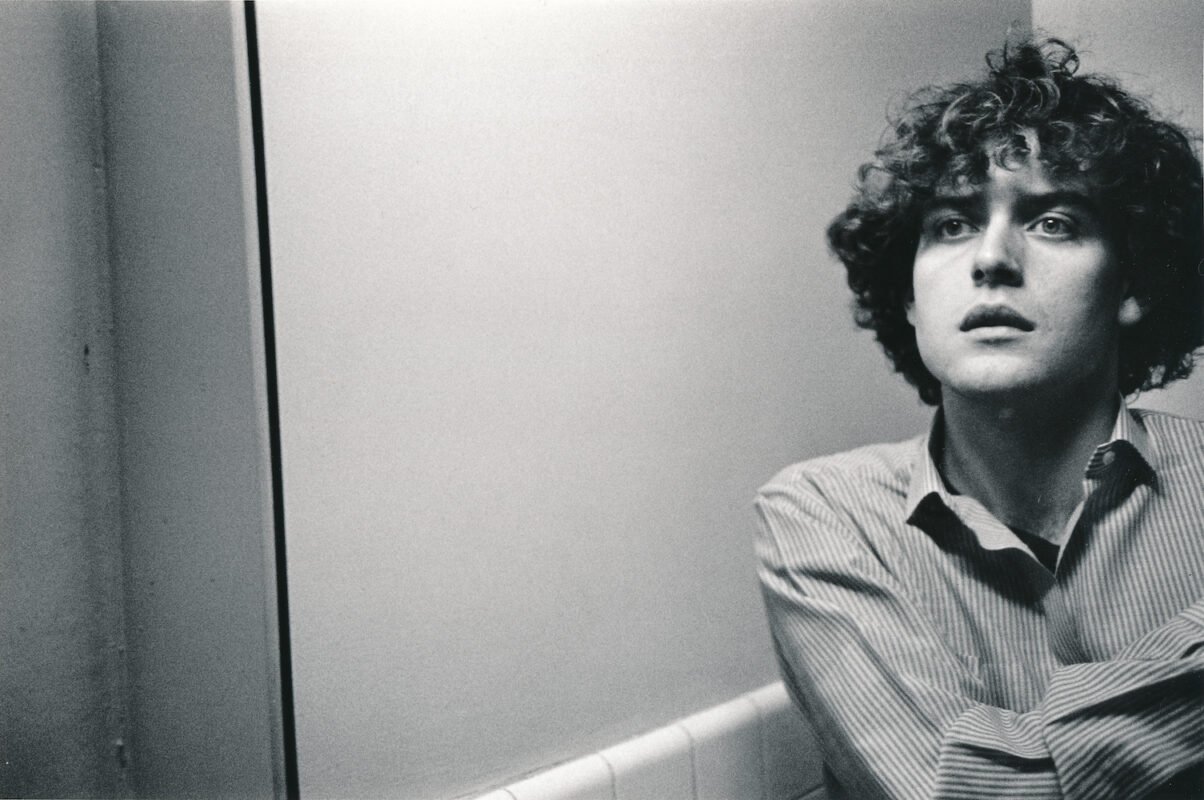

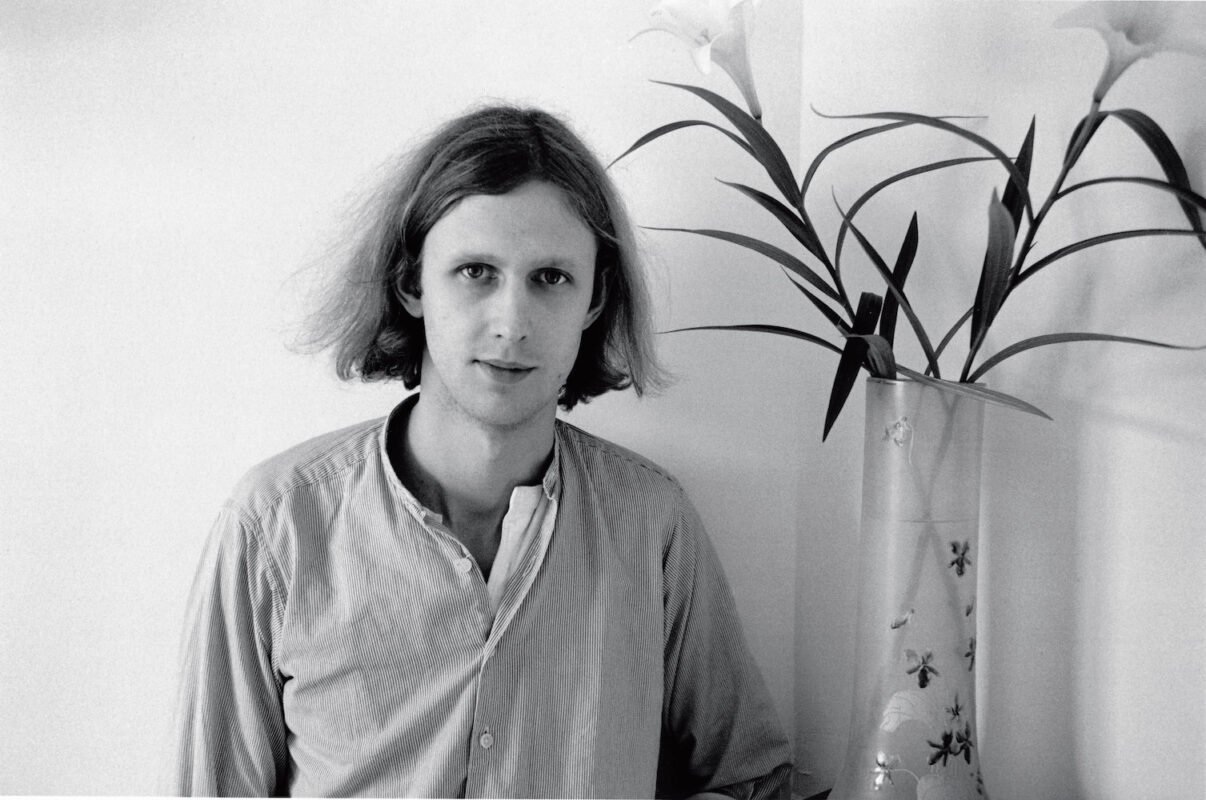

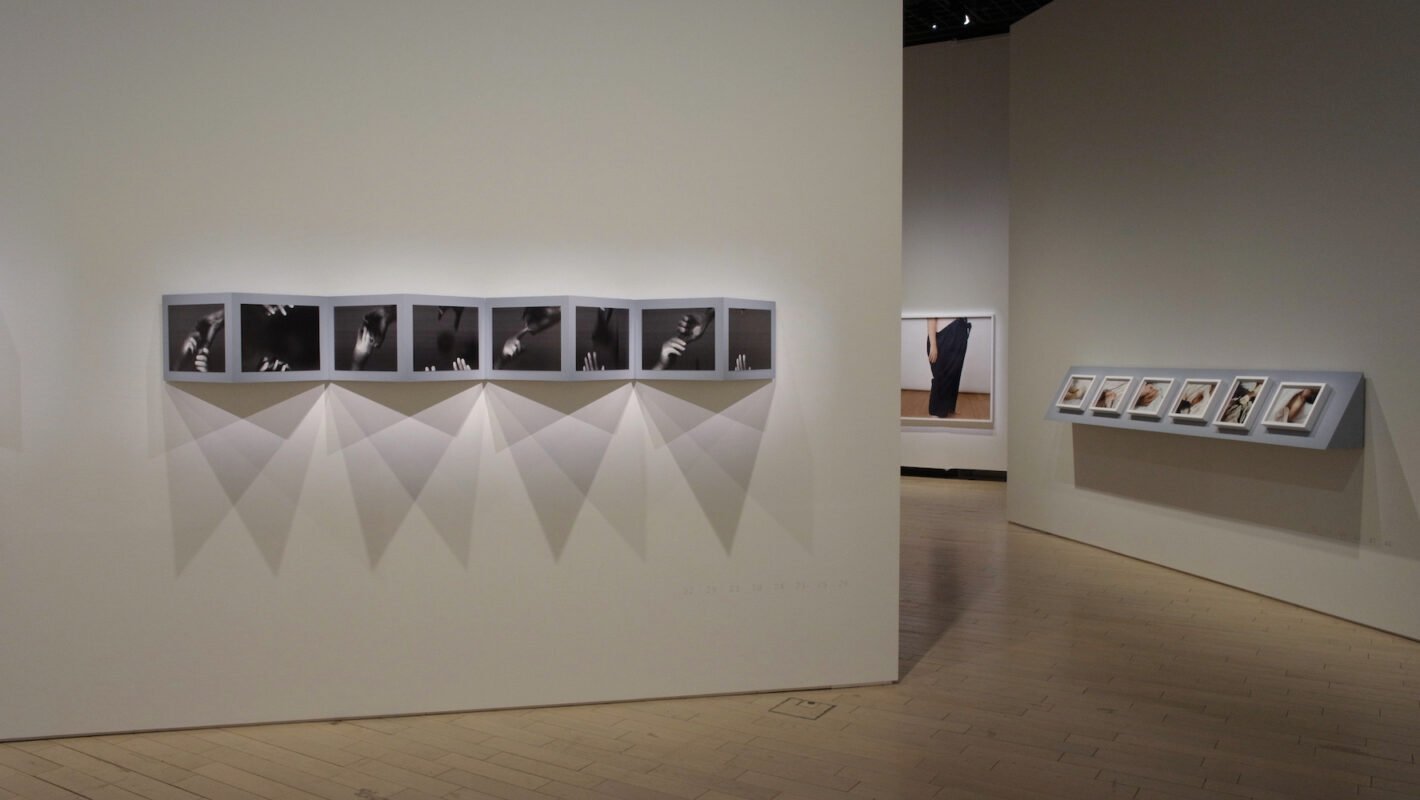

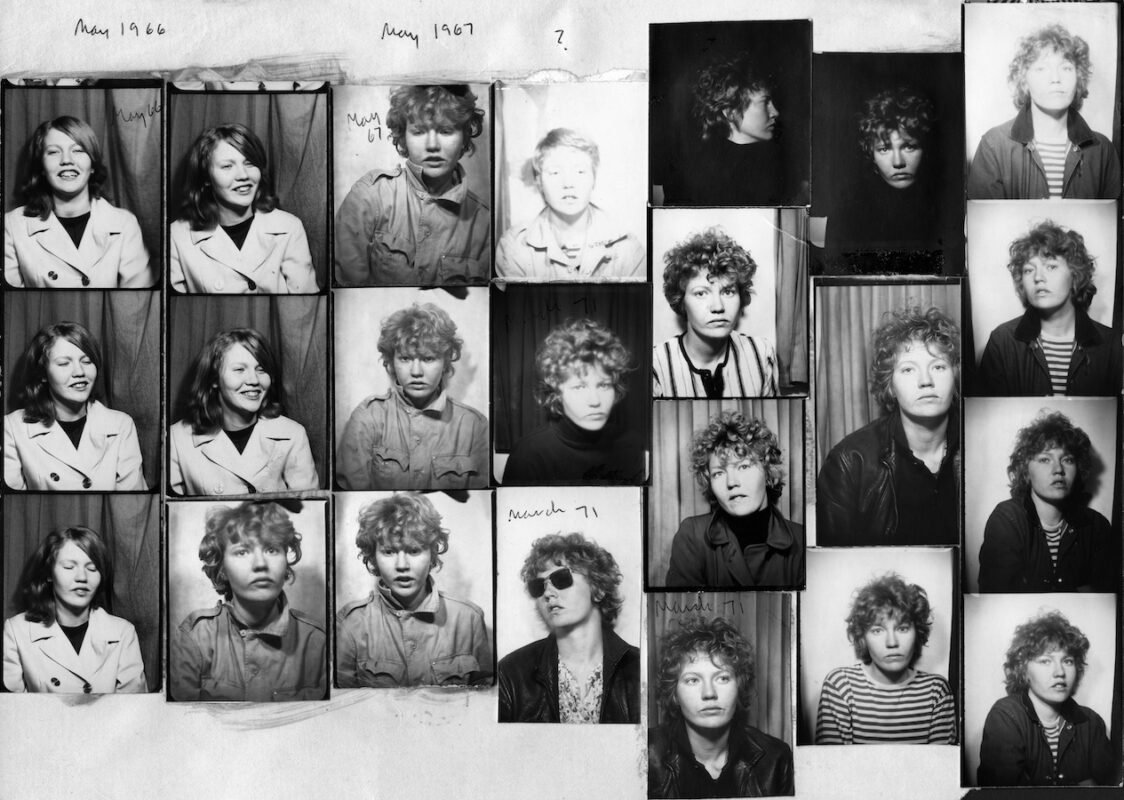

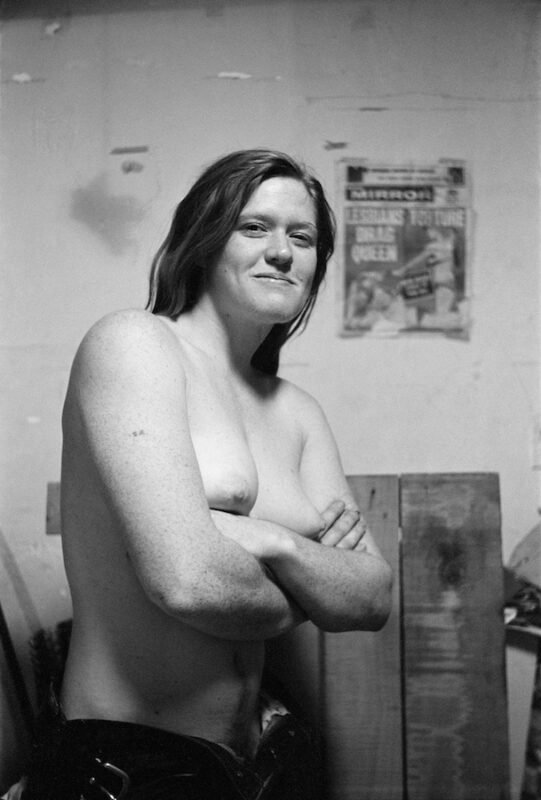

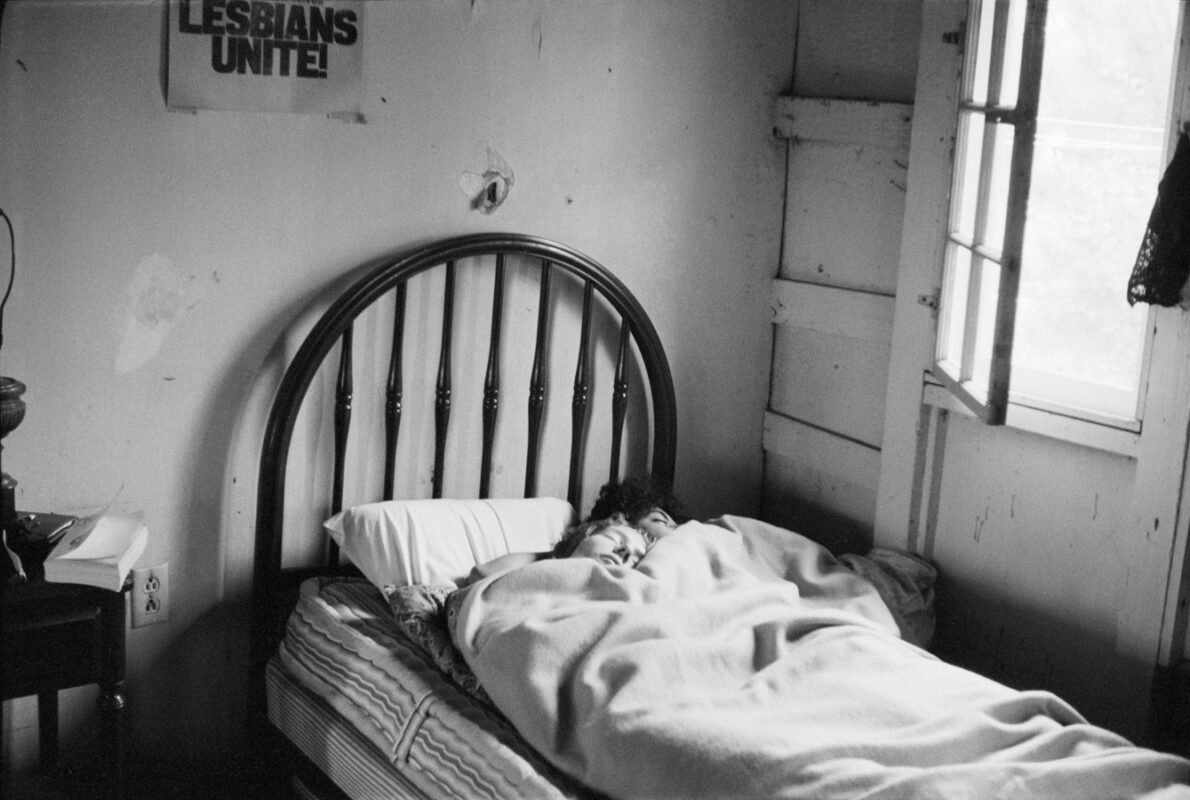

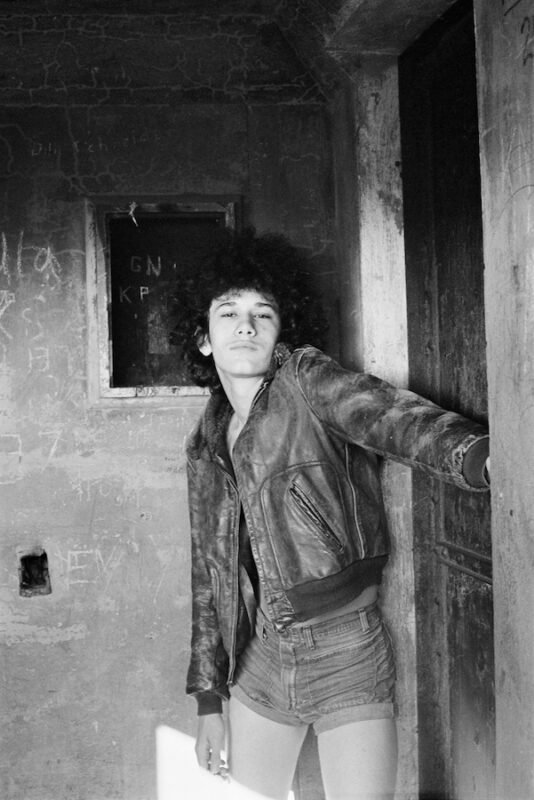

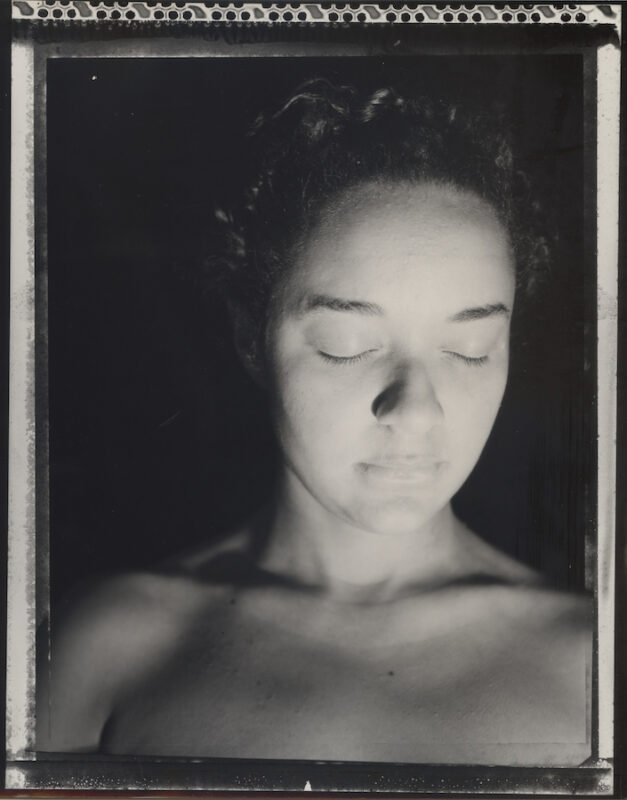

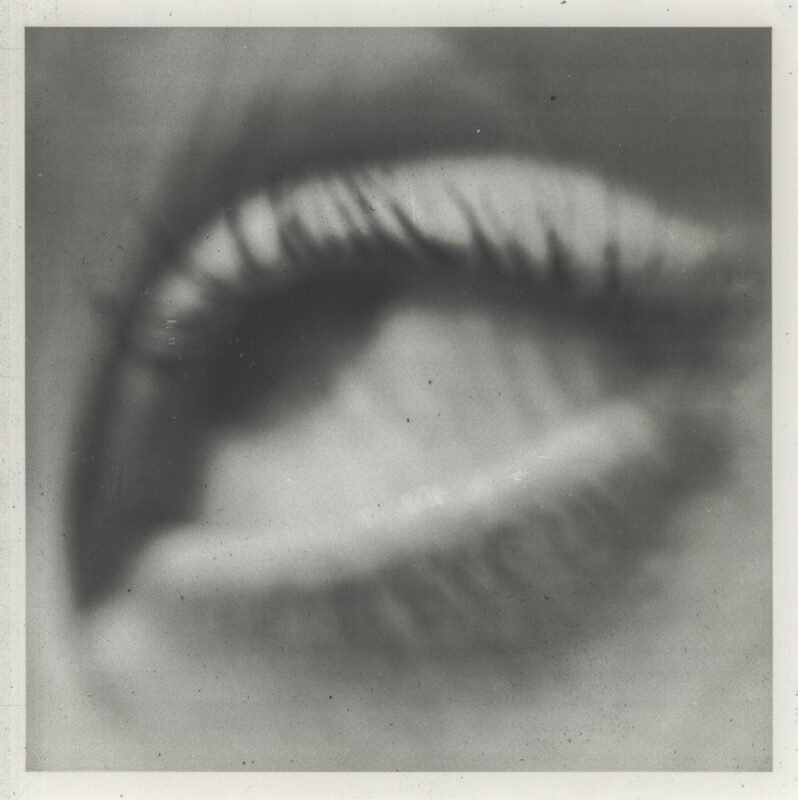

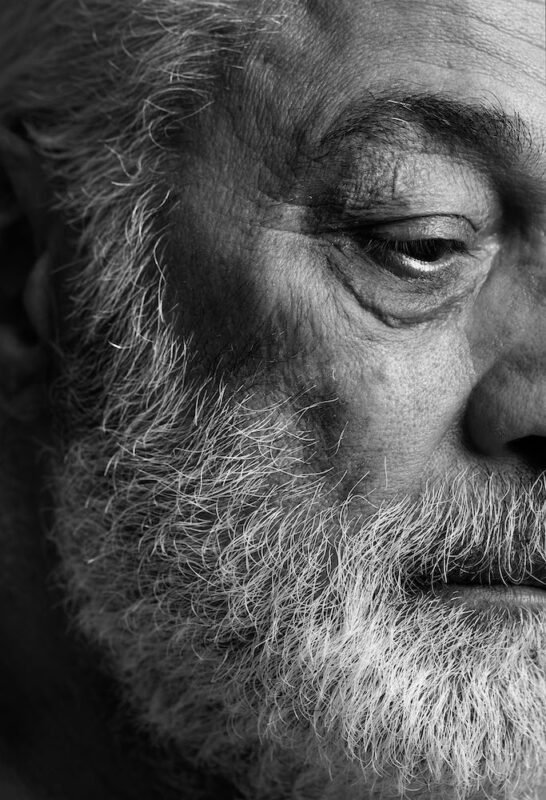

Meanwhile the skyline dominating LUMA presents the work of late photographer David Armstrong, with a retrospective exhibition handled with the utmost care and precision by artist Wade Guyton and curator Matthieu Humery. Two rooms separate black and white and colour, with vast vitrines of contact sheets quietly footnoting the first room. Armstrong’s signature devil-may-care portraits of friends, lovers and fellow artists predominantly from the East Village in New York in the 1970’s through to the 90’s seduce with effortless cool and sexiness. He was a life-long friend of Nan Goldin, photographing people such as Cookie Mueller, Greer Lankton, Mark Morrisroe, and other members of the queer scene. The exhibition is handled beautifully, allowing for a kind of escapism from the visual noise dominating Arles over the opening week.

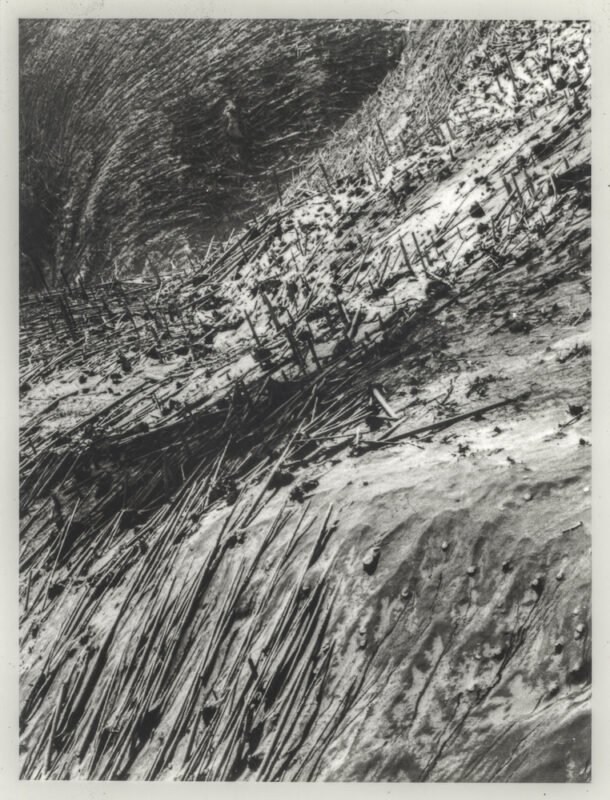

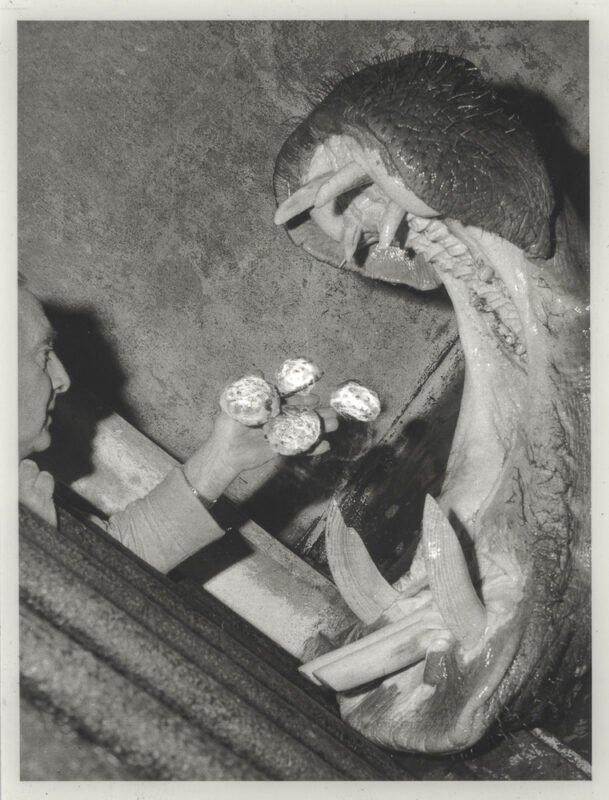

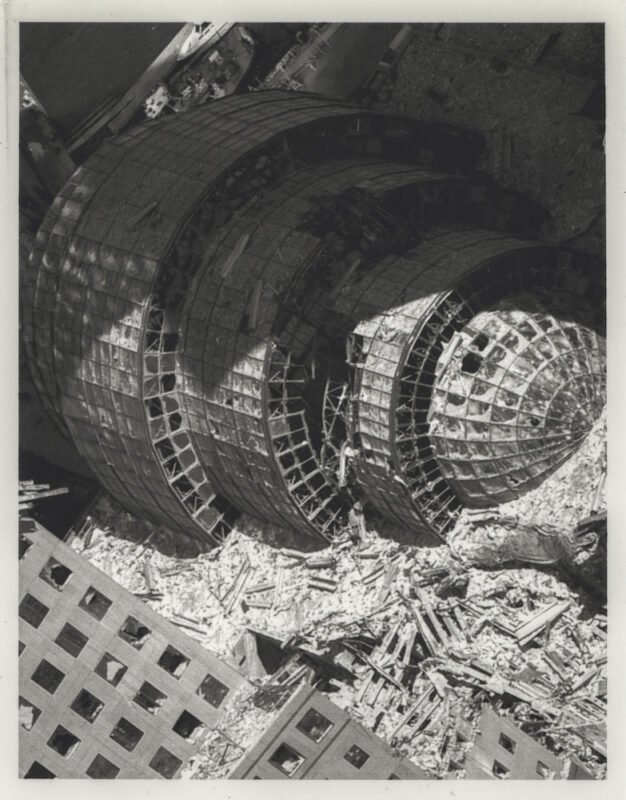

Escaping the midday heat of the festival, Batia Suter’s exhibition Octahydra curated by Francesca Marcaccio Hitzeman took us beneath the ancient Forum, into the Cryptoportiques and the bowels of the earth. In the cool, damp air, and dripping wet walls, two powerful projectors face each other from opposite ends of the cavernous corridor, separated by sheer fabric projection screens and smaller intermediary screens that catch fragments of the images as they pass through. Moving between them, the images dissolve and recombine, decontextualising and abstracting the architectural typologies first presented on the main screens. This is very much a bodily and sensory experience, one that demonstrates both restraint and a precise response to the unique nature of the space. Her work, which I had only experienced in book form until now, translates wonderfully into exhibition form – creating a new register of experience. Many photographers and exhibiting artists at the festival could learn from this kind of thoughtful translation. Too often, the visual and material strategies on display relied on a too-similar, now-familiar material language which permeates the photography world as distinct from the contemporary art world, often resulting in a total flattening of affect and experience. I was left wondering just how many of these exhibitions might have taken another, more appropriate form. Just as not every body of work needs to become a book, not every body of work should become an exhibition.

A notable mention goes to Keisha Scarville, whose work predominantly comprises self-portraiture, reappropriating and embodying the clothing and fabrics left behind by her late mother. We are told that she takes inspiration from Egúngún, also known as Ará Ọ̀run (‘The collective dead’), a masked or costumed figure, of the Yoruba people. Her work is playful, graphic, and working through the processes of grief and absence that so often permeate the material remains of the departed, but with the kind of energy that also takes the work outside of that register. She approximates the absence of the mother, through the positioning of herself in the frame, inhabiting the clothing of her mother, and moving between classical and more experimental forms. A pleasurably graphic mode of self-presentation and exploration.

Meanwhile, Brandon Gercara’s exhibition draws on the volcanic landscape of La Réunion – specifically the Piton de la Fournaise – to forge a poetic and political language of resistance. Inspired by the geological formation of hyaloclastites, their art crystallises new, sustainable spaces for marginalised communities, particularly through the lens of Kwir identity, a Creole reimagining of ‘queer.’ In the films Playback de la pensée Kwir and Conversations and Lip sync de la pensée, Gercara uses drag to transmute personal and collective trauma into spectral, extraterrestrial figures that defy normative social structures. Their practice weaves together activism and art to expose and destabilise the lingering forces of colonialism – gender, racial and class-based oppression – suggesting an emancipatory territory rooted in intersectionality and resistance.

Finally, the talk of the town was undoubtedly Diana Markosian’s exhibition, tucked away upstairs in the Monoprix supermarket near the railway station. Markosian was just seven when her mother took her and her brother from Moscow to the United States in 1996, leaving their father behind without saying goodbye. He returned to an empty apartment and spent years searching for his missing children, desperately writing letters to authorities and strangers alike. In California, their mother cut him from family photographs, erasing his presence entirely. Markosian revisited this deeply personal history in her 2020 monograph Santa Barbara, which reconstructs their migration and her mother’s determination to start a new life. Fifteen years later, she travelled to Armenia in search of her father, an emotional reunion that became the foundation for Father, a project weaving together photography, archival documents and video to explore absence, reconciliation and the painful legacy of their estrangement.

Markosian draws on every tool at her disposal to elicit an emotional response – at times, perhaps too insistently, as with the piano soundtrack that borders on instructive. But the music urges us to experience the work cinematically, inviting us to be swept up in the narrative and given space to dream. This cinematic quality makes the reunion feel as if it is both happening and not happening. On the day I saw it, like many others, I wept – moved by the simplicity of a black-and-white photograph of her father’s shirt, hanging in plastic after being laundered – perhaps reminded of my own photograph of my mother’s dress. There is a moment in the film where Markosian sits across from her father, and they briefly hold hands while staring into each other’s eyes. There is a flicker of pain and relief and love and awkwardness in the eyes of her father in this moment, and this felt direct, poignant and universal. This moment had me totally floored.

When art and culture is at its very best it doesn’t rest on its laurels; it provokes us, it unsettles us, it carves out the space for renewal and reimagining, and it provides us with forms of collective empathy. Despite eternal precarity, art carries with it these responsibilities: to keep asking difficult questions, to do the hard work in the good times and the bad, and to offer a safe environment outside of the banalities and disappointments of everyday lived experience.

That two of the most powerful moments at this year’s festival came not from the official programming – Nan Goldin after the award ceremony, and NO-PHOTO on the fringes – but from artists turning their work back onto the institution and the industry itself, is telling. It reveals the limits of representation without accountability, and of inclusion without political engagement. And yet, these moments also point towards a very different possibility – one where festivals like Les Rencontres d’Arles not only platform voices but also respond to the urgencies those voices name. A transformed festival would not just celebrate disobedience as a theme, but give more space to it as a practice: by refusing neutrality in the face of violence and divesting from oppressive structures, all the while creating meaningful space for dissent, dialogue and action.♦

Les Rencontres d’Arles runs until 5 October 2025.

—

Peter Watkins is an artist and educator based in Prague, Czech Republic. Watkins received his MA in Photography at the Royal College of Art in 2014, and has since exhibited his work internationally, receiving several awards for his ongoing practice. His work is held in the collections of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, and Fotomuseum Winterthur, Switzerland. His book The Unforgetting was published by Skinnerboox in 2020. He is currently Associate Lecturer at Prague City University.

Images:

1-Nan Goldin. Young Love, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian.

2&3-NO-PHOTO 2025 poster campaign. Courtesy Double Dummy.

4-Carol Newhouse. Self-portrait made during an Art and Photography workshop, WomanShare, Summer 1975. Courtesy the artist.

5-Carol Newhouse and Carmen Winant, 2024. Courtesy the artists.

6-David Armstrong, Cookie at Bleecker St., NYC, 1977. Courtesy the estate of David Armstrong.

7-David Armstrong, George in the Water, Provincetown, 1977. Courtesy the estate of David Armstrong.

8&9-Installation views of David Armstrong, 2025, LUMA Arles. Courtesy the estate of David Armstrong. © Victor&Simon – Grégoire D’Ablon

10&11-Batia Suter, excerpt from Octahydra, video, 2024. Out of the Metropolis project, NŌUA, Bodø. Courtesy the artist.

12&13-Installation views of Batia Suter: Octahydra, 2025. Courtesy Out of the Metropolis.

14-Keisha Scarville, Untitled #18, Alma / Mama’s Clothes series, 2017. Courtesy the artist.

15-Brandon Gercara. Joseph 83; from the Conversations series, 2019. Courtesy the artist.

16-Diana Markosian, The Cut Out; from the Father series, 2014-24. Courtesy the artist.

17-Diana Markosian, Mornings with You; from the Father series, 2014-24. Courtesy the artist.

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique and activism

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous Dahmani

• Shana Lopes reviews Agnieszka Sosnowska’s För

• Valentina Abenavoli discusses photobooks and community

• Michael Grieve considers Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler’s posthumous collaboration with their late family member

• Elisa Medde on Taysir Batniji’s images of glitched video calls from Gaza

Join us on Patreon today and be part of shaping the future of photographic discourse