Stacy Mehrfar on The Moon Belongs to Everyone

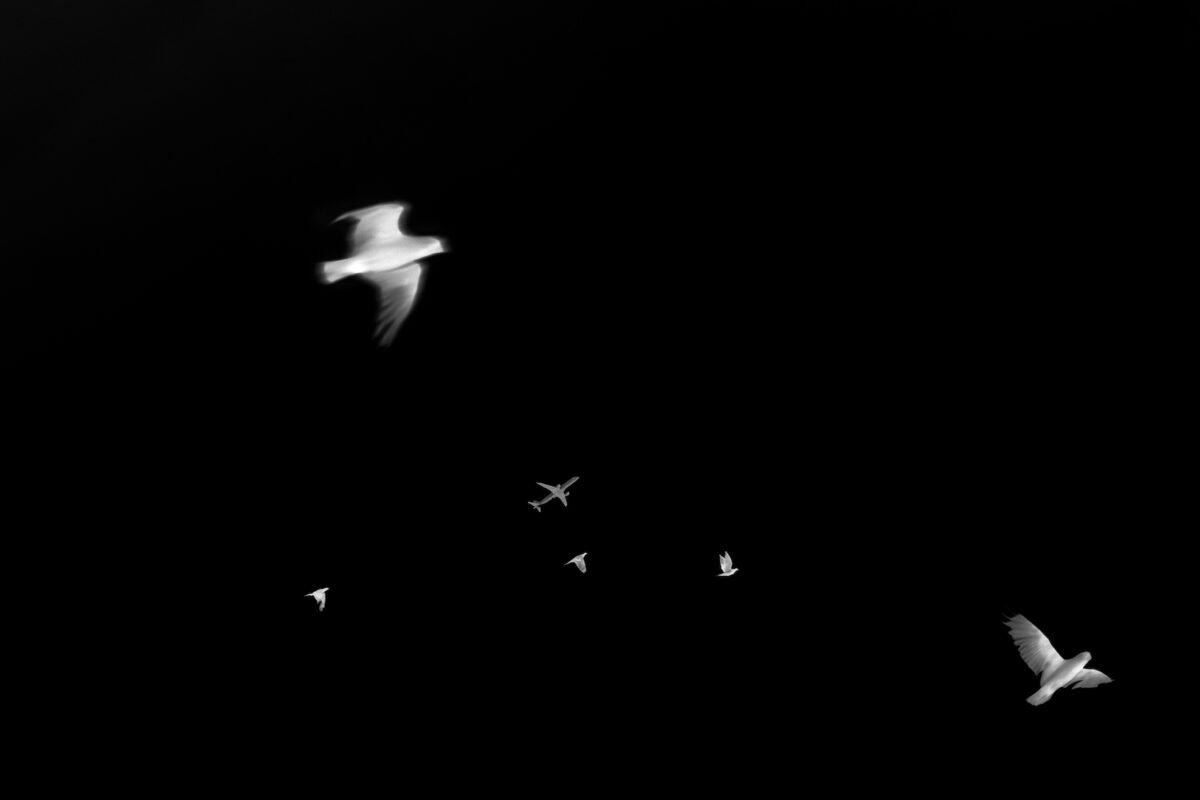

Around the world, politicians are stepping up efforts to criminalise migrants. In the UK, Reform has been calling to scrap Indefinite Leave to Remain. France is implementing sharp cuts in legal immigration and massive deportations of undocumented people. And in the U.S., Trump’s administration issued the Executive Order 14159 ‘Protecting the American People Against Invasion’, which, amongst other directives, expands expedited removal. Against such a backdrop, Stacy Mehrfar’s The Moon Belongs to Everyone, included in this year’s Glaz Festival in Rennes and Bretagne, France, becomes especially pertinent. A visual poem on what it means to relocate, what it means to come back, and the ever-shifting polymorphic meaning of home, the artist speaks with Raquel Villar-Pérez about migration, belonging and identity.

Raquel Villar-Pérez | Interview | 22 Jan 2026

Join us on Patreon

Raquel Villar-Pérez: Can you tell me about The Moon Belongs to Everyone?

Stacy Mehrfar: I grew up in an immigrant family. My parents emigrated from Iran to the United States in 1967, and I was born and raised in New York. The home where I grew up felt as if my parents had brought all of Iran with them – the furniture, the decor, the smells and the sounds were all distinctly Persian. Then I would walk outside the house, and not only was I from an immigrant family, but I was also firmly an American, Jewish and a woman. I lived on that threshold.

As an adult, I became an immigrant when I moved to Australia. I had no intention of ever leaving New York, but I fell in love and married an Aussie. He also grew up in an immigrant family – he was born in South Africa and his family came to Australia when he was 10. He owned a business, and I worked freelance, so I left home and moved to Sydney to be with him. I found myself living in another world, where the light was different. The language, even though we both spoke English, was entirely different, and words and gestures held different meanings. I felt upside down.

My immigrant experience was significantly different from that of my parents and their generation. They came to the United States for economic opportunity and religious freedoms, and remained closely tied to the Persian Jewish community from the moment they arrived in New York. My mother learned English as a child, but my father had very little grasp of the language. They could only speak to their family in Iran once a month. During each phone call, they would schedule the next one to ensure they would keep connected. Letters could take over a month to get back and forth from Iran to New York, and they assumed the Iranian government was reading their letters before releasing them.

In my case, I migrated during a time of globalisation, when I could speak to my family multiple times a day, every day. Yet, despite this, feelings of in-betweenness and unbelonging remained. The Moon Belongs to Everyone is the result of these life experiences. The title reflects something I came to understand: that while we may leave behind homes, languages and landscapes, some things – like the moon – remain constant. I decided to photograph through those feelings of in-betweenness and also to include the experiences of other people who had also immigrated to Australia.

RVP: How did you choose your subjects?

SM: I wanted to ensure that I photographed people from diverse countries and cultural backgrounds. I created specific parameters: for instance, they had to have lived in Australia for at least three years and be between 25 and 45 years old. I didn’t include any refugees, as that experience is not my own.

Through our conversations, I discovered that despite our different origins, we all shared similar experiences of feeling ungrounded, of being between here and there, of no longer belonging to either place.

It was important that the photographs convey this sense of dislocation, allowing the viewer to experience that same feeling of navigating and existing within, unfamiliar landscapes. I photographed throughout Australia and New York state, but deliberately composed the images so none of the landscapes are recognisable – because when one migrates, even familiar places can feel strange.

RVP: How do you present the work?

SM: Throughout the length of the project, I have explored ideas of change associated with ‘home’ and ‘migrant.’ We grow up thinking of home as this steadfast place. However, when you migrate, it changes, and often, it isn’t tied to a physical location. As an immigrant, you are constantly changing, continuously adapting. I wanted the work to be physically different each time it was presented. Initially, it was an eight-channel video installation that was shown twice in Australia, and subsequently, it was published as a photobook by GOST. There are about 70 images in the project, so every exhibition is an opportunity to create a totally different installation, and this is also the premise for Glaz Festival.

RVP: Elusion is, perhaps, a key component in the project. How do you use this as a tool to talk about the experience of migration?

SM: When I moved, I experienced everything very differently; nothing looked the way I had previously understood it, so I wanted to share that experience of looking at something and not immediately grasping what it was. I started with the colour fields; they were flowers that I found in my neighbourhood, which were unlike any flowers that I found in New York. I was amazed by their vibrancy, so I put my camera lens directly onto the petals. What I wanted to document was the colour, positioning colour as a trigger for memory.

I’m always questioning photography and the idea that we know what a picture represents. Why can’t a photograph just be the visualisation of an emotion, a feeling or a sensibility? I want to push against our expectations of what a photograph is.

RVP: Where does the symbology of the moon and the sun used throughout the project come from?

SM: Growing up, I listened to songs in Farsi where the moon is celebrated as the most beautiful thing. There is also a term of endearment, ‘maahe mani,’ which means ‘you are my moon.’ This idea of the moon being something precious has always accompanied me.

When I was making the work, I was thinking about elements that we all experience despite borders. We all have a relationship to the moon and the sun. These elements are experienced across the world. I also thought of the circularity of their motion, how it determines their presence in different regions. Living in Australia, when the sun is up, the moon is up in New York and vice versa. So living on the opposite side of the planet, when my family was looking at the moon, I was looking at the sun. I found this fascinating and comforting.

RVP: You combine three different genres in the project; landscape, portraits and still life. Can you tell me more about the role of each in the work?

SM: The work combines four elements: landscape, portraits, still life and colour fields – each serving a specific purpose.

The colour fields are, as mentioned earlier, extreme close-up photographs of flowers, and in the case of yellow, a school bus. These speak to memory and cultural associations one may have to colour.

Landscape is the key element; it allows me to reflect on the question of what happens when you’re no longer grounded in the place you find yourself in. It was important for me not to have any horizon lines or indications of cardinal directions to convey a sense of loss, fluidity and constant movement.

The portraits feature individuals who shared the same sense of loss that I experienced in Australia – a feeling of being neither here nor there, in-between. Through photographing them, I realised we had our own distinct culture or community: we were those who moved home.

The still lives represent memories – mine and those the others shared with me during our time photographing together – elements that represented home or just comfort. The pomegranate image references a personal memory. As a child, I would fight with my brothers and cousins over who got first dibs on the pomegranate at the Rosh Hashanah seder table. Pomegranates are eaten on the new year to symbolise the wish for a plentiful year ahead. After living in Australia, far away from family traditions, it became a symbol of loss.

RVP: Can you situate The Moon Belongs to Everyone within today’s political climate marked by resurgent conservatism and tighter migratory policies?

SM: The Moon Belongs to Everyone examines how migration reshapes our collective understanding of identity and belonging. It takes an embodied, emotional approach – focusing on the psychological effects of leaving one’s home and the complex process of establishing identity in unfamiliar terrain – rather than a straight documentary approach.

The word ‘immigrant’ has changed so much in my lifetime. Growing up, being immigrants was always a source of pride for my family. By the time I moved back to New York in 2016, the term had become deeply charged. It’s frightening how, especially in the U.S. and Europe, the term has been weaponised to mean ‘other’ – something threatening rather than affirming.

I made this work between 2014 and 2021, as global conversations about immigration and nationhood shifted dramatically. Today, with increasingly restrictive policies and rising nationalism, the project feels even more urgent.

RVP: The project can feel a bit hopeless and despairing. As if we migrants are in an endless pursuit of looking for ‘home.’ Do you think that it is ever found?

SM: There is loss in the work. But home, I’ve come to believe, is found in community. Physical home changes – we change, places change – but everywhere you go, you can find home with the people you’re in community with. Home becomes less about a fixed place and more about belonging, adapting and the connections we build wherever we are.♦

All images courtesy the artist. © Stacy Mehrfar

The Moon Belongs to Everyone runs at Les Champs Libres, Rennes, France, as party of Glaz Festival until 6 February 2026.

—

Stacy Mehrfar is a first-generation Iranian-American artist working with photography, photobooks and video. She has exhibited her works at TEDxSydney, Australia; KMAC Contemporary Art Museum, Louisville, Kentucky; and the International Centre of Photography (ICP), New York. A 2022 Silver List nominee, Mehrfar has received the Joseph Robert Foundation Grant, Puffin Foundation Artist Grant and Australian Postgraduate Award. Her residencies include Interlude, I-Park Foundation and the Wassaic Project. She is a 2025 LABA Lab fellow and Studio Arts resident at the Clemente Centre. Her most recent monograph, The Moon Belongs to Everyone, was published by GOST in 2021. Mehrfar holds an MFA in Photomedia from the University of NSW School of Art and Design, Sydney and teaches at the School of Visual Arts and ICP.

Raquel Villar-Pérez is an independent art researcher, writer and curator whose practice focuses on de- and anti-colonial visual discourses within contemporary art from the Global Majority. She is interested in the work of women-identified image-makers who address notions of migration, transnational feminisms, social and environmental justice.

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique and activism

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous Dahmani

• Shana Lopes reviews Agnieszka Sosnowska’s För

• Valentina Abenavoli discusses photobooks and community

• Michael Grieve considers Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler’s posthumous collaboration with their late family member

• Elisa Medde on Taysir Batniji’s images of glitched video calls from Gaza

Join us on Patreon today and be part of shaping the future of photographic discourse