Framed and defanged: Steve McQueen’s Resistance

Resistance – co-curated by artist and filmmaker Steve McQueen after four years of research – follows the mutual shaping of photography and protest in Britain throughout history, debuting at Turner Contemporary and now on show at National Galleries of Scotland. Charting a century of activism in the UK, Resistance gathers a powerful archive of overlooked dissent. Yet, as Mark Durden writes, in stripping protest of its urgency and historical texture, it risks flattening its force through decontextualised display and selective memory.

Mark Durden | Exhibition review | 12 Dec 2025

Join us on Patreon

Photographs can fascinate because of what they are about. This is the guiding approach to photography in Resistance: How Protest Shaped Britain and Photography Shaped Protest, conceived, curated and branded by the acclaimed artist and filmmaker Steve McQueen, together with Clarrie Wallis and Emma Lewis of Turner Contemporary, currently on show at the National Galleries of Scotland. Beginning with the militant actions of the suffragettes, the show takes us through a century of protest, and includes the hunger marches of the 1930s, anti-fascist demonstrations, the battle of Cable Street, anti-racist marches and protests, the Miners’ Strike, Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, environmental movements, battles for gay liberation and against Section 28, disability rights campaigns. It takes us up to the historical moment of mass protests against the Iraq War in February 2003.

Concentrating on a time before smartphones and the mass uptake of social media, the show is a powerful reminder of what we are in danger of losing in our world of media-controlling techno-oligarchs, misinformation and fake news. It is also very meaningful in light of the recent and disturbing acceleration of the criminalisation of protest in the UK.

With this photography exhibition, everything is about content, what the images are showing us. It is a transparent show in this respect, not overly complex or fussy. Everything is stripped back to the basic and literal function of the photograph as document, to the point there is minimal distraction. And no colour. Everything is in black and white. I remember press pictures of the ‘Don’t Attack Iraq’ anti-war crowds as being in colour. They look a bit odd in monochrome. It is clearly an aesthetic choice. Just like the uniform and fairly neutral display: pictures set behind glass with white mattes and black frames.

As newly printed pictures, sourced from various public archives and personal collections, and with many previously unseen – though it is never made clear which ones they are – their display is without any traces of their original context. Wall captions give info about the protests and also some contexts for the pictures. Photographs are grouped in terms of causes and issues, which means historical pictures are shown in relation to pictures of more recent but related events. Many of the historical pictures are fascinating in themselves: a 1920 photograph of a march by blind people for ‘justice not charity’; a document of the inspection of crates of ostrich feathers at the ‘Port of London’ (to be seen in the context of protests against the use of exotic plumes for hats in the Victorian era); and from 1938, a photograph of the lie-down protest by the unemployed in the rain in Oxford Circus, their bodies partly covered by the signs of their protest: ‘Starved! Protested! Arrested!’

The exhibition starts well with an array of pictures drawn from the campaign for women’s suffrage, opening with a press picture of Annie Kenney. She smiles to camera as she is being arrested, a mark of the complicity between press photographers who were often tipped off about planned actions. From the very outset we are shown how photography plays a part in the publicity of protest and a means of building public support.

A secret press photograph taken of three suffragettes shows them bored and yawning in court as they attend yet another trial. While the photograph was taken surreptitiously, it looks like they are performing to camera, or if not, certainly to the crowd at court. What comes across from the selection of pictures about the suffragettes is how media savvy they were.

While the mandate and driver of the show is what the pictures document, it is how events are pictured that engages us. There is no escaping the power of form here. Certain images become memorable and moving because of the skills, the craft, of the photographer. Tish Murtha’s pictures of the unemployed in her hometown in Newcastle’s West End in the early 1980s, are a good example – raw but also intimate and lyrical in their disclosure of the neglect and waste of a generation.

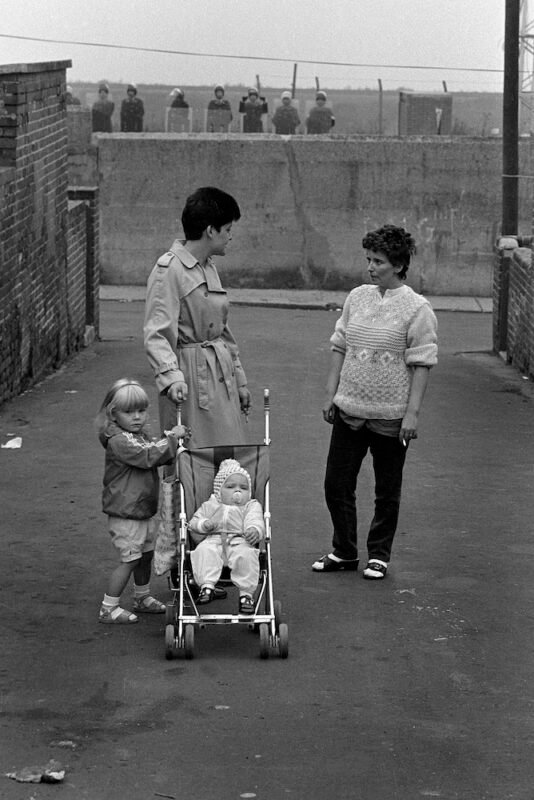

The French photographer, Christine Spengler’s pictures taken amidst the heated conflict during the Troubles, introduce a subtle reportage: the tension and dynamic set up in her portrait of a young soldier in Belfast, standing in the sun on the corner, as a child adorned in a comical mask lingers in the shadows of the street behind him or the tender portrait of a young girl holding a black flag bearing a white cross, standing on a road closed off for an IRA funeral procession in Derry-Londonderry, with the dark presence of the blockade formed by armoured military vehicles and soldiers looming in the background.

A central picture for the show – used for publicity and on the accompanying book’s cover – is Paul Trevor’s depiction of a crowd’s collectivity, as people gather to block the route of a National Front demonstration in New Cross Road, London, August 1977. We are brought close to this crowd, shown not as an anonymous mass but as a gathering of individuals, shouting and cheering, some with raised fists. It is a utopian vision of what is possible through solidarity. In another remarkable picture, by an unknown photographer, a Black passerby is pictured as if he is at the head of a National Front march in support of Enoch Powell. His unfazed presence, and in white-tie formal dress, undoes the power of the rabble of racists behind him.

On 18 January 1981,13 Black people were killed in a fire during a house party in New Cross, London. It is suspected to have been a racist arson attack. The largest Black-led demonstration in Britain followed outrage over the silence that the tragedy was met with, both by the Conservative government and the national media. Pictures of the protest, included in the exhibition, commemorate the dead – people held large photographic portraits of lost loved ones – and also serve to show the solidarity and resilience of those taking part. Geoffrey White’s aftermath picture, showing people gathered to look at the burnt-out three-story Georgian terraced house is one of the most painful and haunting documents in the show.

In 1977, during the first day of the mass picket by female Asian workers over working conditions at Grunwick film-processing laboratories, Andrew Wiard pictured strike leader Jayaben Desai confronting police. Its pictorial power rests upon the way in which it sets the inexpressive faces of two of the policemen against the expressive energy of her rage and anger. Their eyes are shadowed by their helmets, and both possess an uncanny likeness to one another (they must be twins, an odd doubling of the blank face of the Law).

Protest itself is an action and signal, something done to be seen, to be looked at, and, of course, to be photographed. But there are also pictures of people who are not clamouring for attention, quieter moments that convey a sense of the everyday texture of lives and situations in Britain amidst all the protests and causes: the miner and his family watching Scargill on Channel 4 news; the women taking a break from a hunger march, tending to their sore feet, John Deakin’s portraits of delegates at the fifth pan-African Congress, in October 1945, in Manchester’s Chorlton Hall.

An intriguing inclusion in this show are documents, by Jill Posener, of culture jamming, pictures showing witty retorts scrawled over sexist advertising campaigns on billboards from the late 1970s onwards. In answering back to other representations, this sabotaging of marketing messages opens up a critical relation to the commercial image realm and in some respects takes us away from the people-focused documentary line central to this show.

In a 1992 photograph by Samena Rana, a sign with the words ‘Piss on Pity’ partly covers a collection box figure of a bespectacled child by what was then known as the Spastics Society (now Scope). Like the graffiti-altered ads, Rana’s protest mobilises the power of language (the pithy and punchy campaign slogan adopted by disability rights groups) to counter misrepresentation, in this case the depiction of disabled people as helpless and pitiful. The power of protest through the use of language, on signs and placards, while present is not central in this show. Philip Jones Griffith’s picture of a ‘ban the bomb’ protest in Aldermaston, for example, rests upon the wit of a single handmade sign held aloft amidst the crowd bearing a drawing of a dinosaur between the message: ‘Too much armour/ Too little brain’.

Resistance is good at introducing lesser known photographs drawn from a century of protest in the UK, as well as alerting us to less familiar moments of dissent. But it over-reaches itself, attempts to take on too much and has an oddly basic, utilitarian approach to the photograph throughout. Severing pictures from any trace of their original contexts, the show fails to give us sufficient sense of how some of the images sourced and scanned and printed for exhibition, were originally used and seen. Would seeing some of the leaflets, pamphlets, newspapers, police files, magazines, etc, in which some of these pictures first circulated, distract? Would it not add to the richness and impact of the photographs on show? On the matter of what is shown and not shown, there is almost nothing about the history of solidarity with the Palestinian cause in Britain. Among the sea of ‘Don’t Attack Iraq’ placards, in Andrew Wiard’s photograph of the February 2003 Anti-War mass protest, there is a small cluster of ‘Free Palestine’ signs, a recognition of the plight of Palestinians following the Israeli massacre in the Jenin refugee camp in 2002. But that is all. ♦

Resistance: How Protest Shaped Britain and Photography Shaped Protest runs at National Galleries of Scotland until 4 January 2026.

—

Mark Durden is an academic, writer and artist. He is Professor of Photography and the Director of the European Centre for Documentary Research at the University of South Wales. He works collaboratively as part of the artist group Common Culture and, since 2017, with João Leal, has been photographing modernist architecture in Europe.

Images:

1-Unknown photographer, Annie Kenney (an Oldham cotton mill worker) arrested in London, April 1913. © Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo

2-Eddie Worth, An anti-fascist demonstrator is taken away under arrest after a mounted baton charge during the Battle of Cable Street, London, 4 October 1936. © Associated Press/Alamy Stock Photo

3-Paul Trevor, Anti-racists gather to block route of National Front demonstration, New Cross Road, London, August 1977. © Paul Trevor 2024

4-Chris Miles, Notting Hill Carnival, London, 1974. © Chris Miles

5-Keith Pattison, Police operation to get the first returning miner into the pit. Joanne, Gillian and Kate Handy with Brenda Robinson, Easington Colliery, Durham, 24 August 1984. © Keith Pattison

6-Keith Pattison, Biran, Paul and Denice Gregory watching Channel Four News. Cuba Street. Easington Colliery. County Durham. November 1984. © Keith Pattison

7-Pam Isherwood, Stop Clause 28 march, Whitehall, London, 9 January 1988. © Bishopsgate Institute

8-Henry Grant, Anti-nuclear protesters marching to Aldermaston, Berkshire, May 1958. © Henry Grant Collection/London Museum

9-Andrew Testa, Protesters against the construction of the Newbury bypass occupy trees to prevent their destruction, Berkshire, 1996. © Andrew Testa

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique and activism

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous Dahmani

• Shana Lopes reviews Agnieszka Sosnowska’s För

• Valentina Abenavoli discusses photobooks and community

• Michael Grieve considers Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler’s posthumous collaboration with their late family member

• Elisa Medde on Taysir Batniji’s images of glitched video calls from Gaza

Join us on Patreon today and be part of shaping the future of photographic discourse