Ryudai Takano’s collisions of a sensing body

Ryudai Takano’s photography, now on view at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, asks us to recognise the body not just as a subject of the image, but as an actor, agent and sense-maker within the exhibition experience. Moving through his installations across multiple visits, Duncan Wooldridge writes that Takano’s staging of seriality, surprise and fragmentary montage – spanning portraits, cityscapes, photograms, and experimental display methods – unseats fixed categories of photography to reveal a field of continuous becoming.

Duncan Wooldridge | Exhibition review | 20 Nov 2025

Join us on Patreon

In his recent exhibition at Tokyo Photographic Museum, now open at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, Ryudai Takano makes tangible how bodies interact, catalyse and collide. In and around his images, the body is more than a subject matter: it is an actor, an agent, a sensor, and a sense-maker. Even though two of Takano’s most well-known motifs are his portraits and the studies of the figure, he calls upon us to take the body as more than something to be observed or placed on display.

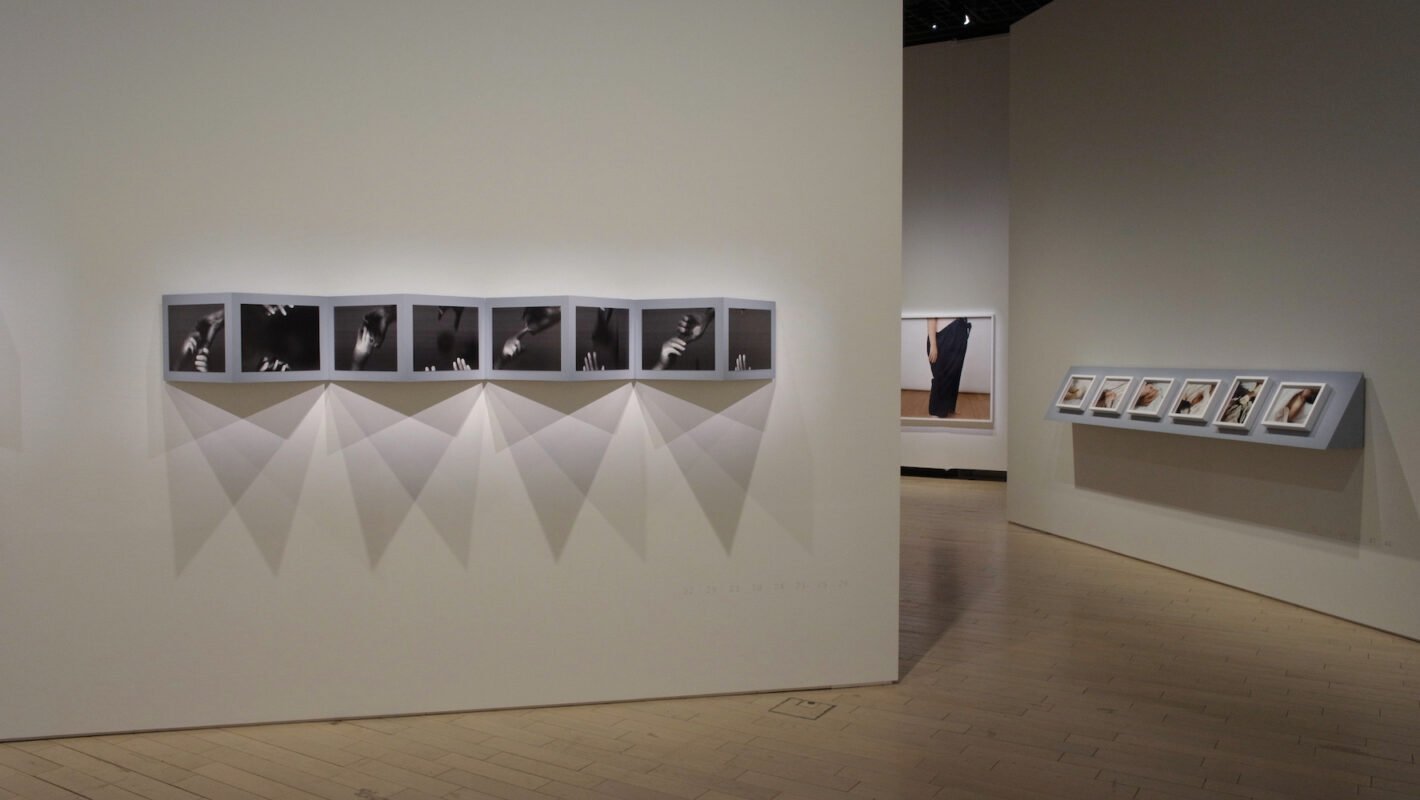

Entering the exhibition space, open plan but with many columns and freestanding walls inserted by the artist, a wide array of work appears visible – a first play on the exhibition model of the ‘survey’, which provides a feast for the eyes. But this perception of an overview is quickly shattered: the viewer’s own body is called upon: there are no prompts nor prescriptive paths about how to begin, and the exhibition has an infinite number of routes. Seriality and surprise are held in a balance. If for a moment the display coheres in our visual field, it is fractured with only an extra step. New combinations appear, and specific sightlines, once smooth, become increasingly complex. On my first visit, I stepped to the left towards a cityscape image, to reveal a sequence of works from the series Kasubaba 2 – large studies of the city’s junk spaces and chaotic interminglings, where Takano has recorded areas of the city he initially wanted to reject or characterise as ugly or disordered, as a challenge to his own aesthetic assumptions. Such images form part of a much larger inquiry about how photography can be used to contest conventional modes of seeing.

Across from these cityscapes are studies from the related Daily Snapshots, which move between outer and inner worlds with a poetics drawing attention to the ordinary and extraordinary. From visual cues of the city (repeated views of Tokyo Tower from the artist’s apartment) to haptic impressions from the kitchen table, we’re momentarily rooted in a space that feels structured, oriented around place. With a step or two more, the exhibition is no longer so linear: in view, a monumental photogram of two bodies climbs the wall; then another photogram – this time smaller, showing a pair of hands, one in focus, the other soft – appearing close to the moment of touch (though this is an illusion: one is near and the other further away, close only on resulting the picture plane). Suddenly our own bodies become visible as shadows. Our trace is caught in a light installation which lifts our image up along the wall – speaking to Takano’s engagement with the Japanese avant-garde and the work of Jiro Takamatsu, whose shadows replaced the object in a series of paintings. Cast in front of us, our shadow is not only visible here, but is seen by a camera, which relays that image once more onto a new screen. We are suddenly multiple – what was a solitary space has become crowded.

But let’s start over. Takano’s photography is made of prompts, catalysts and collisions. A sense of possibility is drawn out of what are sometimes recognisable visual forms. In many of his works we feel at first as though we are on stable ground: a cityscape, an observational image, a full-length portrait. This is even true of the photogram, or short video works, experiments with flatbed scanners and a concern for the installation environment. But as his projects are increasingly seen in relation, it becomes clear that Takano’s work cannot be explained through style or any of our standard visual categories. He is neither a documentarian nor chronicler, and even less does he seem to be an auteur, constructing a way of seeing with a singular sensibility. Instead, he unseats assumptions – and gives access to a distinctive and critical multiplicity that is crucial to Japanese photography but rarely foregrounded in exhibitions which tour to the West.

On my next visit, I entered and headed right. Presented first to the body, below waist height and laid out in vitrines, are works from the 1:1 series – which promise reality, showing as they do bodies printed to actual size. Close scrutiny of the images reveals they are made up of accumulated exposures – sheet film images stacked and printed together, so that a small black line becomes visible at the join of each frame. Lifelike in their scale, they are nevertheless fragmentary, making visible a significant photographic conundrum: to photograph the body wholly captured by the lens, with less detail, or to record its subtle, distinguishing features, but to need an image that is assembled from a series of parts?

Above the vitrine rests an image of a statue – its left hand covers its face, as if resisting its already ghostly representation – and an image of a shadow, fragmented so that its source is unclear. Around the perimeter wall, there are more spectral representations: documentation of one of Takano’s light installations, and a video of a train journey which proceeds at great speed, so that the architecture and waiting passengers appear only momentarily amongst a blur of transmission patterns. Each are works with specific contexts and signification, but here in their combinations and collisions, Takano reveals a concern to negotiate spaces around and between the categories that images inhabit. It might be tempting to ask of photography that it settle into a singular, almost fixed form – and for images to belong to discrete projects, and be shown in those established contexts – but what Takano reveals, as is apparent across a lineage of experimental Japanese photography to which he belongs, is that images themselves, like us, are continuously finding new patterns and new possibilities. What we see in Takano’s most fragmented, or seemingly disjunctive arrangements – are just such a concern to see in a way that is not reduced to a static positionality.

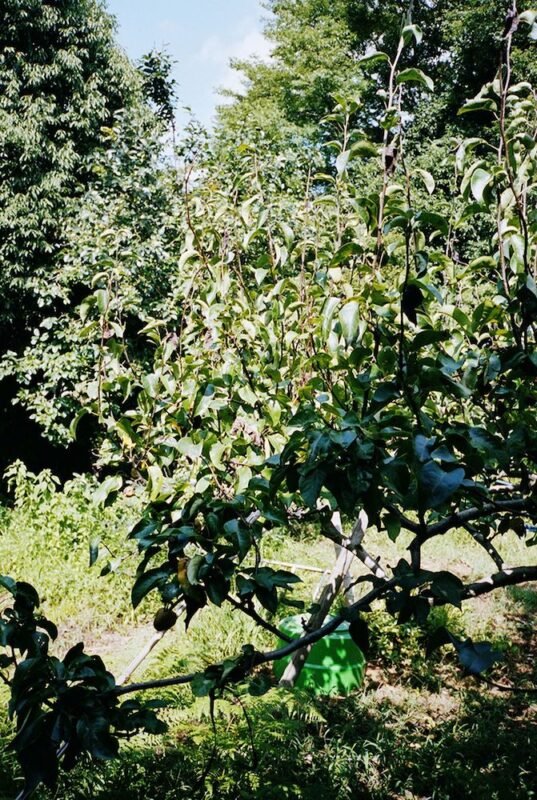

Let’s reset one last time. On my third visit, I headed straight ahead. I have not exhausted all of the available options, but neither is this plausible nor necessary. Between a two-body black and white photogram and a colour photograph of tree branches filling the frame, I step forward, moving into a space with two large colour figures from the series In My Room. These are portraits cut at the waist, a little larger than 1:1 scale, and one meets my eye when I enter. The works introduce Takano’s study of the ambiguities of sexuality and the fluidity of the self, collapsing bodily binaries to fold them into a wider interest in the one and the many: Takano’s earlier Caramaru, not on display, deliberately entangled the bodies of performers until their singularities were hard to reconstitute. In My Room is a series of photographs made, as the title suggests, by photographing subjects – whose relationship to the photographer remains unclear – in his room in a Tokyo apartment. Like Caramaru, the works are a type of performance made for the camera, a site for complexity and resistant ambiguities. They displace the privacy of the bedroom and place it into public view, at the same time as they gesture towards a debunking of the purity or hygiene of the studio.

In the portraits, a subtle ambiguity and mixing of masculine and feminine signifiers are held in suspension by the camera’s decisive half-body crop. Their gaze meets ours, intently and without compromise. Immediately around a corner from one of the portraits, the lower half of a body is hung at the same height in a spatial assemblage. The body is fragmented and sliced in two, and here offers a reconstruction. Only by moving do we make this visible, and here the body is rendered neither whole nor fixed, but subject to our curious, animating gaze. Takano is well known in Japan for having had his work with male and trans nudity censored: in his work the disappearance of genitalia is subversively dramatized even if it cannot be seen (doubly invisible to those of us brought up in a western context, who will recognise their absence, but perhaps fail to recognise a very different social and political friction. Takano is continually pushing at what an image can do or show. In its mix of the familiar and the experimental, continually shapeshifting, Takano proposes a photography concerned both with contact and touch, and which stages this concern in the form of a collision. What results is open-ended: this it seems, is a useful remedy to our concern for distinction and fixity.♦

All images courtesy the artist and Yumiko Chiba Associates. © Ryudai Takano

Ryudai Takano: kasbaba Living through the ordinary runs at Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, Japan, until 7 December 2025.

–

Duncan Wooldridge is an artist, writer and curator, and is Reader in Photography at the School of Digital Arts, Manchester School of Art, Manchester Metropolitan University. He is the author of John Hilliard: Not Black and White (Ridinghouse, 2014), To Be Determined: Photography and the Future (SPBH Editions, 2021) and Co-Editor of Writer Conversations (1000 Words, 2023).

Images:

1>7-Installation views of Ryudai Takano: kasbaba Living through the ordinary at Tokyo Photographic Museum, 27 February – 8 June 2025.

8-Takano Ryudai, 2002.09.08.M.#b08 from the series Stand up, Kikuo!, 2002.

9-Takano Ryudai, 2012.08.12.#b30 from the series Daily Snapshots, 2012

10-Takano Ryudai, 2015.10.28.#a28 from the series kasubaba 2,2015

11-Takano Ryudai, 2023.03.24.sc.#048 from the series CVD19, 2023

12-Takano Ryudai, 2019.12.31.P.#03 (Distance) from the series Red Room Project, 2019

13-Takano Ryudai, Wearing a purple camisole with lace (2005.01.09.L.#04) from the series In My Room, 2005

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique and activism

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous Dahmani

• Shana Lopes reviews Agnieszka Sosnowska’s För

• Valentina Abenavoli discusses photobooks and community

• Michael Grieve considers Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler’s posthumous collaboration with their late family member

• Elisa Medde on Taysir Batniji’s images of glitched video calls from Gaza

Join us on Patreon today and be part of shaping the future of photographic discourse