When the mask slips: Cindy Sherman

On the uninhabited island of Illa del Rei, where a former British naval hospital now houses Hauser & Wirth Menorca, Cindy Sherman’s latest exhibition and her first solo show in Spain in over two decades is on view. Spanning eight series from across her near 50-year career, The Women stages a carnival of ageing flappers, social climbers and fashion phantoms; with deadpan wit and grotesque precision, Sherman’s portraits expose the desperate contortions of femininity and the moment the mask begins to slip, writes Charlotte Jansen.

Charlotte Jansen | Exhibition review | 5 Sept 2025

Join us on Patreon

Cindy Sherman’s latest exhibition, The Women, can be viewed by taking a boat to the rugged, uninhabited island of Illa del Rei from the port of Mahon, Menorca. Disarming in its picturesque beauty, Illa del Rei was home to a large naval hospital from 1711 until 1964. More recently, Hauser & Wirth opened a gallery here, where currently Sherman’s works are on view until October, when the island closes to the public. A collection of the gruesome instruments and contraptions used for treatments is now housed in a neighbouring museum occupying the former hospital buildings.

The shadows of this past of physical suffering and transformation seem to be an appropriate prologue to viewing Sherman’s works, in which she contorts herself, often painfully, into embarrassing, awkward and desperate characters performed to perfection to her camera. The Women, though not intended to be comprehensive, encompasses eight series, made during different periods of Sherman’s near 50-year career, from stretched stereotypes of silver screen starlets, amalgams of fashion wannabes, to mash-ups of guffawing society women, and fading flappers. The exhibition engages head-on with Sherman’s persistent, preoccupying subject: the female figure. The women are never ‘real’ women, of course – they are pastiches of women, of women’s experiences, of women’s struggles and desperation. They are portraits about portraiture and the nature of representation, and the fallacy that being seen is the same as being understood.

Arranged in a flipped chronology, the show starts with recent-ish large-format commissions for fashion magazines: works known as Ominous Landscapes (2010-12) for Pop magazine, using clothes from the Chanel archives, and a 2016 Harper’s Bazaar commission, where the details just don’t add up: Sherman’s model character wears a Marc Jacobs coat and bag and clutches an iPhone in a sylvan scene. In another image, dressed in couture and yellow elbow-length gloves she stands in front of a mountain, but the figure almost measures up to the landscape and her stockinged feet – left out of the frame – would logically be planted in the surrounding sea. This is all part of Sherman’s trenchant humour, playing with colour and scale to unapologetically take over spaces in and out of the frame with her women, their uncanny, grotesque grandeur unavoidable. Something is always off. It is just as hilarious to me that Sherman would do these editorials with actual couture given the fact she has smashed the market, sales-wise. I can’t imagine having one of these staring at me at home.

These fashion photographs that both mock the industry that forces women to be looked at this way, and are at the same time subsumed by it, are an intriguing entry point to the exhibition and the contradictions always present in Sherman’s portrayals of women. Through their fastidious observational details, Sherman perfectly captures the attitude of a type of woman, from a moment in time – familiar enough to feel, as exhibition curator puts it “I’ve been to a party at her house.” Sherman is certainly the most astute observer of female social mores, she an ‘impersonator’ of women, as Jerry Saltz wrote. Yet to me there is a shift from her gaze towards the women she performs as in the early years – in say the bus riders, or the femme fatales of the Untitled Film Stills – to something more daring and darkly ambiguous in later works. This, after all, is how women look at each other too. Repulsion became an essential part of Sherman’s works after the 1980s and she seems to abandon herself to it. Then again, that may be the ruse – repulsion is in the eye of the beholder. I had nightmares about the Fairy Tale and clown images I saw at the National Portrait Gallery in 2019, part of Sherman’s first UK retrospective. This exhibition doesn’t include those, but does well in varying the techniques, scale and pace – though endlessly inventive within each image, Sherman’s shows can have a strangely monotonous feel as a viewing experience.

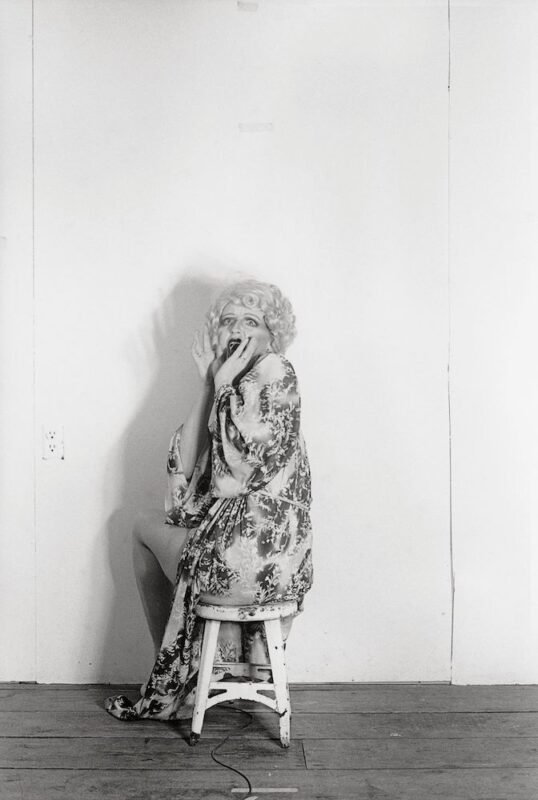

As women we all find ourselves particularly cornered in this system of images, hyper aware of our own image, hypervisible or invisible – both fates equally awful. The Women are products of our image-based environment, one shaped first by theatre, cinema, and later the intrepid influence of fashion magazines, high society and celebrity worship culture. As a woman nearing 40, it’s excruciating at times to look at say the large-scale flappers – made between 2016-2018. Flappers are the perfect Sherman subject since they themselves often emulated Hollywood stars, and were progressive, sexually liberated figures of modernity. Sherman however depicts them long after their prime, glamorous but melancholic – sad, because they’re old? Again and again, Sherman presents the twisted acts of self-contortionism society demands of us, to stay youthful, dress well, groom, smile. Ageing will ultimately betray us, and Sherman shows us, through her grinning, gargoylesque female figures, that the camera’s role in all this isn’t kind. She reveals with a dead pan wit, the hideousness of a mask that’s slipping.

As I look, I also think about Sherman herself, and what happens to women artists when they become world famous. Sherman has managed to remain quite an enigma, by today’s standards. Her work has become, if anything, less commercial, less aesthetically appealing and politically appeasing over the years. Yet as famous as Sherman is, scholarly interest in her work seems relatively unvaried – certainly compared to male counterparts of her status. I’ve come to think of this as the Cindy Sherman paradox. Sherman is undoubtedly one of the most famous ‘photographers’ (some would dispute the categorisation) alive today, one of the only artists working in photography to truly be considered a household name. She is famous for being the most expensive female photographer, and still holds the biggest ever auction sale ($3.89 million) for a single photograph by a woman. (She has held that record since 2011, which is also an indictment of how little the market has moved for women in photography in more than a decade.)

These ideas about value, both in terms of her cultural cachet and commercial gravitas, often eclipse Sherman’s work. Here, curator Tanya Barson offers a fresh look at Sherman. This is one of a spate of new Sherman shows in smaller cities in Europe of late (FOMU Fotomuseum Antwerp, the Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens, in Switzerland at Photo Elysée, and now Hauser & Wirth, Menorca) seeking new ways to see Sherman in places she isn’t so well known. The Women is Sherman’s first exhibition in Spain in a generation (her last was at the Reina Sofia in 1996 – many of the works in The Women were not included in that show, or were made since then).

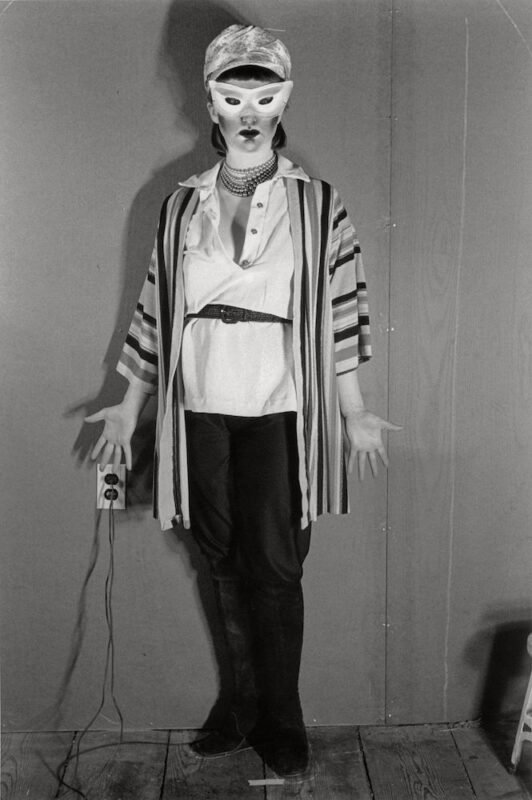

The real treat of this exhibition for me, though, were the very early series, the small black and white images known as the ‘murder mystery’ and ‘line up’ pictures made in 1976 and 1977, while still a student at Buffalo State College. Some of the images from this series were included in the National Portrait Gallery show, but here they have more space and vibrate differently. Here’s a young and unknown Sherman, aged 23, already rapt with self-staging: dressed in eclectic, everyday outfits I can imagine were thrifted on a budget, or borrowed from a friend’s or her own wardrobe, a kaftan and espadrilles, then stockings, suspenders and a bowler hat. The same belt is styled differently. Some wear masks, others are masked with heavy make-up. The bare wooden floorboards and the socket on the wall give them a looser, improvised edge – though with Sherman even then you can imagine it was all meticulously planned. They have energy, and so much to say with so little.

In the line-ups, her characters all take up the same strange pose, body turned slightly to the camera, hands spread in a typically off-kilter Sherman gesture – “Ta-da!” they seem to declare.♦

All images courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth Menorca. © Cindy Sherman

Cindy Sherman. The Women runs at Hauser & Wirth Menorca until 26 October 2025.

—

Charlotte Jansen is a British Sri Lankan author, journalist and critic based in London. Jansen writes on contemporary art and photography for The Guardian, The Financial Times, The New York Times, British Vogue and ELLE, among others. She is the author of Girl on Girl: Art and Photography in the Age of the Female Gaze, (HACHETTE, 2017) and Photography Now (TATE, 2021). Jansen is the curator of Discovery, the section for emerging artists, at Photo London.

Images:

1-Cindy Sherman, Untitled #566, 2016

2-Cindy Sherman, Untitled #568, 2016

3-Cindy Sherman, Untitled #550, 2010/2012

4-Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #6, 1977

5-Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #24, 1978

6-Cindy Sherman, Untitled #369, 1976/2000

7-Cindy Sherman, Untitled (the actress at the murder scene), 1976/2000

8-Cindy Sherman, Untitled #508, 1977/2011

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique and activism

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous Dahmani

• Shana Lopes reviews Agnieszka Sosnowska’s För

• Valentina Abenavoli discusses photobooks and community

• Michael Grieve considers Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler’s posthumous collaboration with their late family member

• Elisa Medde on Taysir Batniji’s images of glitched video calls from Gaza

Join us on Patreon today and be part of shaping the future of photographic discourse