What We’re Reading #5: Autumn 2025

From vaporwave-inflected exhibition-making to the recurring debates around Diane Arbus’ work, the latest instalment of What We’re Reading gathers texts that follow the circulation of style, ethics, politics, and power through curation, criticism and photography – exploring, by turns, where art is made palatable and where it speaks with urgency. Ariella Aïsha Azoulay considers how photographs from Gaza might resist their conscription into state propaganda, while Mariam Barghouti’s Eyes of Truth mourns the killing of Palestinian journalists, exposing an economy that prizes accolades over protecting media personnel.

Thomas King | Resource | 18 September 2025

Join us on Patreon

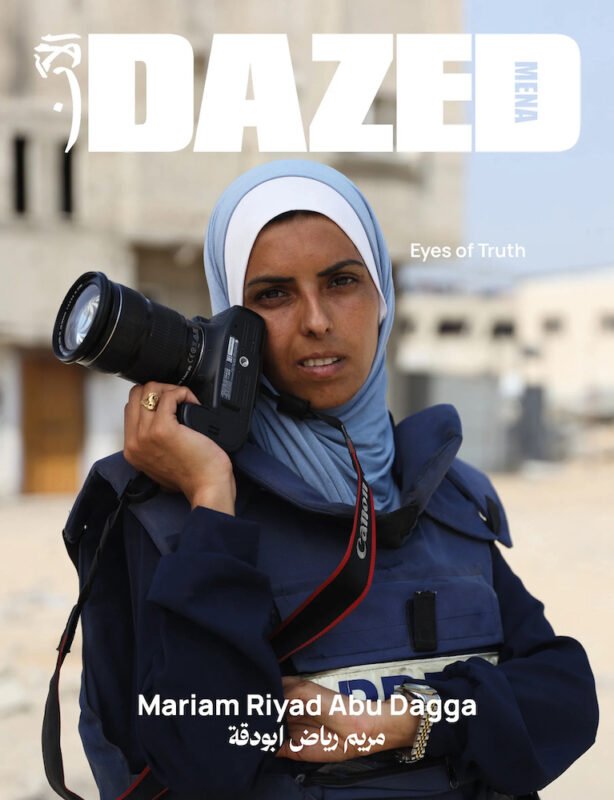

The Eyes of Truth | Mariam Barghouti for DAZED MENA, September 2025

“You see us only in trends of certain events, which would last for hours and then that’s it. We’re just numbers for the world, or non-existent.” So said photojournalist Mariam Riyad Abu Dagga, who was photographed and interviewed for DAZED MENA Issue 3. She was brutally killed just two weeks later by Israeli forces in a targeted strike on Nasser Hospital, along with four other journalists, Ahmed Abu Aziz, Hussam al-Masri, Mohammad Salama, and Moaz Abu Taha. Barghouti writes about Mariam’s wrenching decision to send her son Ghaith out of Gaza after their home was bombed, the loss of her mother soon after and Mariam’s own death.

As Israel’s campaign of slaughter continues, and a leaked White House plan reportedly calls for Gaza’s total displacement under U.S. trusteeship for a decade, Barghouti passionately denounces Western media that offers only belated awards, headlines and hollow sympathy, while never protecting or defending Palestinian media personnel: ‘Say their names, cite their work, defend their lives. Widen the record until it can be held. Allow Ghaith to inherit a world that finally learned to listen.’

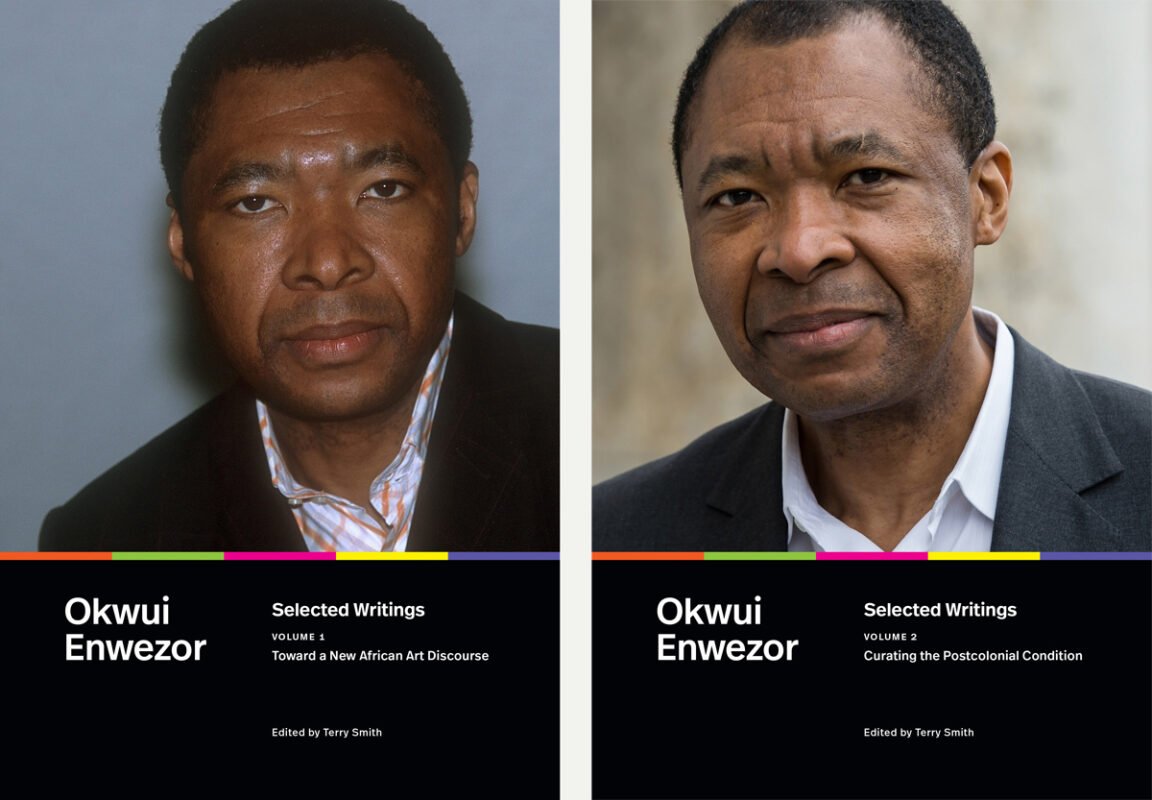

Okwui Enwezor | Oluremi C. Onabanjo for 4Columns, September 2025

Duke University Press have published two volumes of selected writings from the larger-than-life figure, Okwui Enwezor, offering an invaluable resource for understanding his multifaceted contributions to contemporary art and curatorial practice. In her review on 4Columns, MoMA’s Oluremi C. Onabanjo casts a clear and discerning eye on the late writer’s intellectual and curatorial legacy; his essays and exhibitions (including his selection to curate the Documenta 11 in 2002) consistently challenging Western-centric art discourses, destabilising conventional notions of geography and periodisation, and foregrounding historically marginalised perspectives. While acknowledging Enwezor’s ‘lack of substantive engagement with Black feminist theorists’ and other contemporary critiques, Onabanjo emphasises a rare synthesis of literary sensibility, curatorial ambition and poetics that positions his varied contributions as foundational for future generations of artists, scholars and curators. These volumes, she writes, ‘demonstrate the continued utility of examining Enwezor’s positions – not only for what he engendered, but for what he provoked.’

A Massive Diane Arbus Exhibition Does So Little | Hakim Bishara for Hyperallergic, June 2025

Hyperallergic’s coverage of the Diane Arbus: Constellation exhibition at New York’s Park Avenue Armory sparked a mixed chorus of responses in the publication’s Instagram comments, reflecting the contentious ethical debates still surrounding her work. In his review, Bishara immediately flags Arbus’ ‘freak photographs of disabled, disfigured, and disenfranchised people,’ often ‘ambushed in asylums and hospitals,’ as caught in a classist gaze and exhibited without confronting this long-standing ethical fault line. He argues the show’s labyrinthine installation, lack of chronology or thematic grouping, and ban on visitor photography turn 455 images into an ahistorical maze, stripped of context, labels and narrative. Pushing back, there are those reminding that Arbus’ work arose from long and sustained collaborations with those she photographed, suggesting there is more at stake in Arbus and photography more broadly than a Sontagian critique allows – which Bishara, unlike other viewers of the show, doesn’t seem to see past.

A Story of Friendship, Fraud and Fine Art with Orlando Whitfield | Extraordinary Creatives, August 2025

Less what we’re reading and more about what we’re listening to is Ceri Hand’s podcast Extraordinary Creatives. Her vast experience and sensitivity as a host invite guests to share candid reflections and engage in thoughtful conversations about contemporary creative practice. In an episode with Orlando Whitfield, author of All That Glitters, he recounts meeting and befriending Inigo Philbrick at Goldsmiths, University of London, charting the dealer’s meteoric rise and the scheme that became one of the most audacious scandals in art-market history. Through Philbrick’s path – from an internship at White Cube to a network of connections that carried him through various corners of the art world – Whitfield reflects on the possibilities of betrayal in friendship, the breakdowns that ripple through personal and professional relationships, and the bewildering mechanics of value within contemporary art. He also opens up about his own struggles, sharing the moments that drove him away from a field where, in his words, “most artworks have no intrinsic value whatsoever… emotion becomes economics.”

Seeing Genocide: Weaponisation of Images | Ariella Aïsha Azoulay for Doubledummy, July 2025

Anonymous collective, NO-PHOTO, presented a site-specific activation during the opening week of Les Rencontres d’Arles 2025, and to mark the occasion, a new edition of Doubledummy’s free newspaper was released, featuring Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s Seeing Genocide: Weaponisation of Images.

Azoulay, whom we also discussed in the previous What We’re Reading, following her interview with ArtReview, writes in this text (first published in Boston Review in 2023): ‘There is no such thing as an image of genocide. But images in plural, made over time, can be used to refute the terms of Israel’s battle of images.’ As urgent now as it was then, she goes on to say: ‘The images coming out of Gaza – at least when Israel hasn’t shut down the electricity and Internet – can only falsely be called images, since they capture the people who are calling to stop the genocide in rectangular immaterial forms. These are not discrete images of what has happened but visual megaphones calling us to recognise the decades-long genocide and to stop it now.’

The Rise of Vaporwave Curating | Rahel Aima for Frieze, July 2025

Writing to a malaise that haunts today’s global art exhibitions, Rahel Aima describes a drift toward a vaporwave-inflected curatorial style that cushions political crises in a haze of poetic vagueness and aestheticised melancholy. Its signature is a languid, lyrical framing, a ‘passive voice’ of curation favouring a soothing but hollow affect of community and care that anesthetises political urgency. I’m less convinced of this as a particular ‘style’, or mode, than as a symptom of spaces of suspension where power operates. The task, I think, is not simply to curate with greater ‘stakes,’ but to challenge the conditions that enforce palatability, that render ‘good feelings about bad situations’ comfortably consumable. Perhaps the pressing question, since it is all too true that there exists a ‘dangerous assumption that the art world is inherently progressive, even radical – and that a singular ‘art world’ exists at all,’ is where, and under what circumstances, curation might, if it can, escape these symptoms? ♦

—

Thomas King is Editorial Assistant at 1000 Words and currently undertaking an MA in Literary Studies (Critical Theory) at Goldsmiths, University of London.

Images:

1-Cover of DAZED MENA Issue 3: Eyes of Truth

2-Covers of Okwui Enwezor Selected Writings, Volume 1. Toward a New African Art Discourse and Okwui Enwezor. Selected Writings, Volume 2. Curating the Postcolonial Condition, edited by Terry Smith, Duke University Press

3-Installation view of Diane Arbus: Constellation, 2023–24, The Tower, Main Gallery, LUMA Arles, France © Adrian Deweerdt

4-Ceri Hand: Extraordinary Creatives

5-Cover of Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Seeing Genocide: Weaponisation of Images, Doubledummy

6-Screenshot of frieze.com

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique and activism

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous Dahmani

• Shana Lopes reviews Agnieszka Sosnowska’s För

• Valentina Abenavoli discusses photobooks and community

• Michael Grieve considers Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler’s posthumous collaboration with their late family member

• Elisa Medde on Taysir Batniji’s images of glitched video calls from Gaza

Join us on Patreon today and be part of shaping the future of photographic discourse