How can hair be a political symbol?

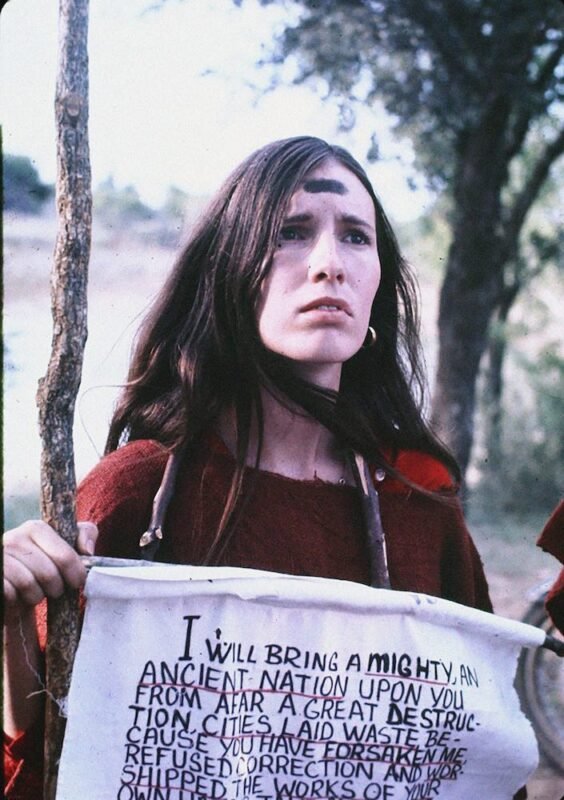

At Museum Folkwang, GROW IT, SHOW IT! investigates the relationship between hair, identity and gender performance across cultures. Spanning 150 years of photographic history, from Victorian cartes de visite to TikTok screenshots, the exhibition presents hair as both personal expression and a political symbol. Drawing on lived experience and cultural movements – feminism, queer identity, civil rights, and post-colonial struggles – Song Tae Chong charts the shifting significance of hair over the course of time.

Song Tae Chong | Exhibition review | 28 Nov 2024

One of my favourite sets of childhood memories is of my grandmother and I. Every morning before I went to school, she would carefully sit me down in front of the fire that she had built in our living room. My socks would be hanging on the smoke screen, warmed for my always too cold feet. Out came her comb, and she would carefully part my hair down the middle, quickly putting my hair into one of three hairstyles: a ponytail, two long braids down my back, or my personal favourite, one long braid starting at the nape of my neck done in the traditional Korean style for young girls. She would either adorn my hair with a ribbon or barrettes, but would always tie up my long strands with hair elastics that had big plastic balls attached. They would sit on my head, like a crown of precious plastic gems. The daily ritual that my grandmother and I had ended once I entered my preteen years and embarked on my own path of hair self-discovery.

When I braid my own hair now, although it is never as neatly and symmetrically arranged as when she did, I think of her and these moments we had, ones that I knew she had with her own grandmother. It was those memories that came flooding back as I opened the pages of the sprawling catalogue produced in conjunction with the exhibition of the same name, GROW IT, SHOW IT! A Look at Hair from Arbus to TikTok by Museum Folkwang in Essen, Germany.

Early on in the exhibition, Hoda Afshar’s triptych of images from the series Turn (2022) depicting women both braiding and holding hair, the braids both ordered and fragile as tendrils escape their pattern and are blown by the wind, speaks to its prevailing themes: connection and community. The subject of hair is explored through a variety of media, from art photographs to images from fashion and advertising as well as anonymous vernacular photographs. These images speak to the ways in which every day people use hair as a means of identity formation and assertion, cultural and social connection, whether for personal, social and political reasons and, of course, for aesthetics.

Spanning approximately 150 years of photographic activity, the catalogue also situates hair within historical contexts. Highlighting queer, feminist, post-colonial, and oppositional politics as well as conventional beauty standards and representations, the photographs assembled show how all of these movements have shaped and reshaped our understanding of hair as visual culture. The catalogue and exhibition serve as both an overview of hair as style and as political and cultural communication. Led by Thomas Seelig and Miriam Bettin, it is an ambitious and expansive curatorial endeavour utilising a wide array of representations of hair. Cartes de visite showing flowing locks of Victorian era hair and screenshots from TikTok refer to the long-standing relationship between hair as the subject of photography and image culture.

Punctuating a diverse and extensive survey of images are critical essays, placing these works within discourses that help to anchor them within a critical context. Lori L. Tharps’ essay “Hair I am” speaks to the legacy of disruption as well as cultural erasure via hair within the history of African people, both as colonised in situ as well as in the forced diaspora of the circum-Atlantic slave trade. Broken lineages, broken cultures, erasure of community building and status symbols, all of this played out in the politics of hair. She writes, ‘For better or worse, the hairstyles worn by African American people, from the 18th century through modern times, continued to signal a person’s status in society. From their politics to their profession, Black hairstyles supposedly said it all.’ Many of the featured works help to illustrate this idea. In a photograph from the archives of The Awa Women’s Group at the Bopp Social Center, a group of women are shown reading and laughing together, each with a unique head wrap as adornment and personal expression of style. A photograph of Angela Davis, with her afro, show how the disruption of attempts to control and tame Blackness played a pivotal role in political movements. The series by Nakeya Brown Sof-m-Free, Afro Curls, X-Possessions: Black Beauty Still Lives (2020/2024) depict objects of self-care, the material culture of black beauty and the symbolic codes understood and shared amongst black women as well as the impact that these products and their packaging had on beauty standards.

GROW IT, SHOW IT! also looks at the importance of hair and its relationship to identity and gender performance across different cultures. Paul Kookier’s Untitled 2020 is both a photographic abstraction and stark depiction of male body hair, to be viewed as a symmetrical form while at the same time challenging the visual culture of male body representation. Images from Satomi Niyoung’s ’70s Tokyo LONG HAIR INVERTED, itself a study on the typology of the hairstyles of the time, suggests the disappearing self, in silhouette or as the inverted image, only distinguished by the outline and shape of hair.

GROW IT, SHOW IT! with its various points of emphasis invites the viewer to think again at the photographs that they have looked at, providing essential frameworks for interpretation. The project obliges viewers to read the semiotics of hair with renewed perspectives, across contexts and time. Viewers are invited, even nudged, to look closer, to probe deeper, to survey the wide array of photographs presented. The images also invite nostalgia and moments of levity. As historical and social and cultural indicators and signifiers, these representations of hair or even its absence within certain visual cultures ask us to reconsider its place in our own lives and how we construct meaning. ♦

GROW IT, SHOW IT! A Look at Hair from Arbus to TikTok runs at Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany, until 12 January 2025

—

Song Tae Chong is a Berlin and New York based photography curator, advisor, and writer. Her research focus is on postcolonial visual culture, epistemologies of memory and documentary photography. She is currently a Trustee of the Martin Parr Foundation and teaches photography and theory at UE Berlin.

Images:

1-Hoda Afshar, “Untitled #4”, from In Turn, 2022. Courtesy Milani Gallery, Meeanjin/Brisbane © Hoda Afshar

2-Chaumont-Zaerpour, Untitled, 2023. Published in The Gentlewoman

3-Dorothea von der Osten, Untitled, 1950s

4-Anna Ehrenstein, Western Girl, 2017

5-Suffo Moncloa, Gucci / The Face Issue 9, 2021

6-Graciela Iturbide, Mujer Ángel, Desierto de Sonora, Mexico, 1979

7-Viviane Sassen, “Kine”, 2011, from Parasomnia. Courtesy Stevenson Gallery © Viviane Sassen

8-Paul Kooiker, Untitled (Hercules), 2020. Courtesy tegenboschvanvreden, Amsterdam © Paul Kooiker

9-Nakeya Brown, “Sof-n-Free” from X-Pressions: Black Beauty Still Lifes, 2020

10-Torbjørn Rødland, Legs and Tail, 2020

11-August Sander, Secretary at Westdeutscher Rundfunk in Cologne, 1931/1982. © The Photographic Collection/SK Foundation for Art and Culture – August Sander Archive, Cologne; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

12-Tessica Brown, Gorilla Glue Girl, 2021. TikTok Reel, 59 seconds

13-Thandiwe Muriu, Camo 2.0 4415, 2018

14-Helmut Newton, Courrèges, French Vogue, 1970. © Helmut Newton Foundation, Berlin

15-Rineke Dijkstra, Almerisa, Wormer, the Netherlands February 21, 1998

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique, and activism.

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age.

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect.

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries.

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto.

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous R. Dahmani.