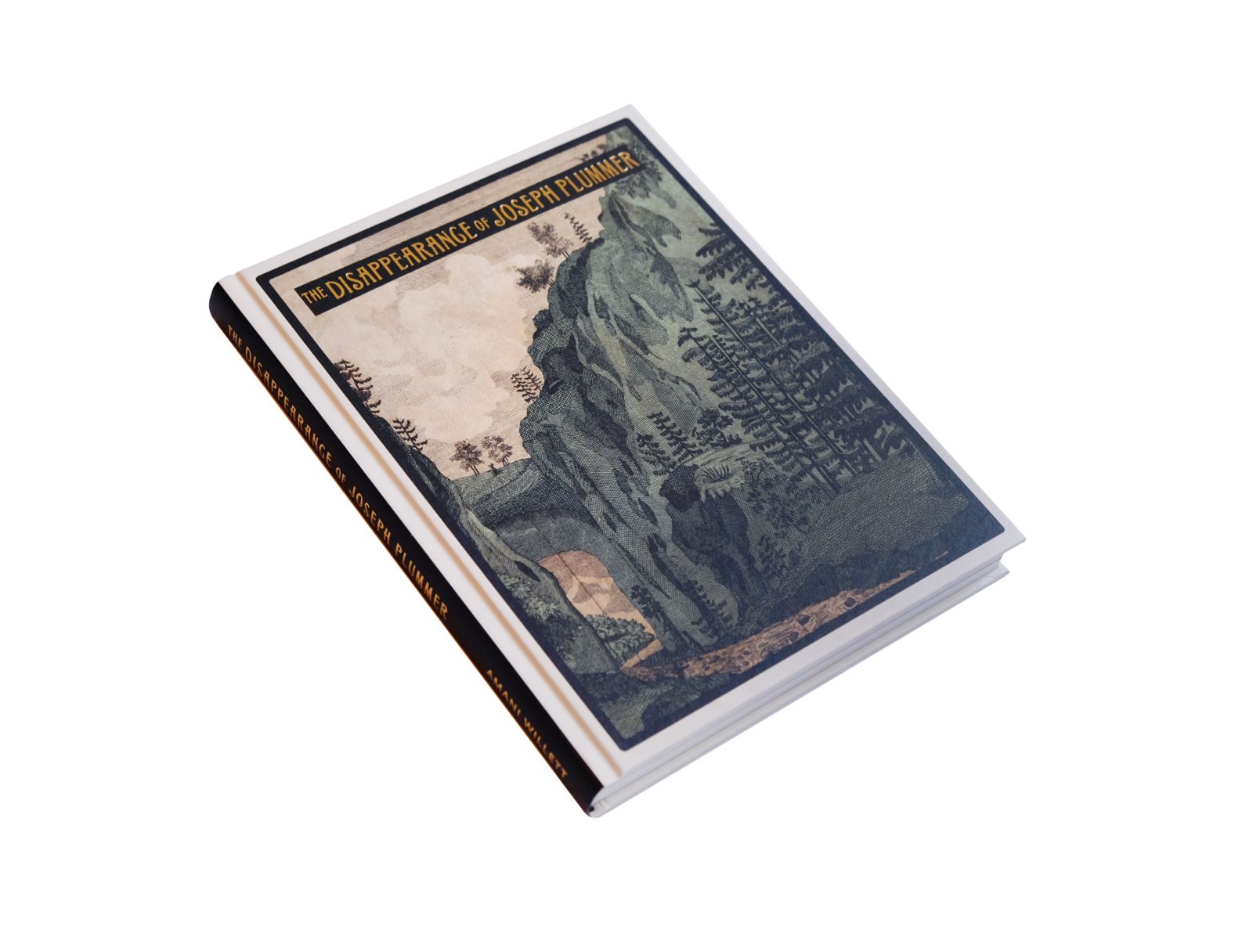

Amani Willett

The Disappearance of Joseph Plummer

Overlapse

In the 1970s, American photographer Amani Willett’s father purchased several acres of New Hampshire forest that a local hermit named Joseph Plummer had disappeared into in the late 1700s, and lived in for 69 years. The two of them, Willett and his father, have rambled those landscapes together ever since, finding traces of Plummer’s legend still lurking there. ‘Getting lost’, Willett tells us simply at the end of his new photobook with Overlapse, The Disappearance of Joseph Plummer, ‘seems to be the point’.

But first to the very beginning. The flurry of images that open the book are of a figure, blurred and hazy, retreating from the camera as they make their way through heavy snow. They are starkly reminiscent of Ori Gersht’s representation of the philosopher Walter Benjamin in his 2009 video, Evaders, in which a figure, playing the part of Benjamin, trudges slowly and purposefully through dark, snowy forest. In the cultural historian Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide to Getting Lost she writes of Benjamin, ‘In Benjamin’s terms….one does not get lost but loses oneself, with the implication that it is a conscious choice, a chosen surrender, a psychic state achievable through geography’. Willett, who gets just lost enough to learn new things about the landscape each time, but never lost enough not to return, seems struck by this man who went all the way, and never left himself a trail back homewards.

‘Joseph Plummer is remembered because he wished to be alone’, Willett says. What would it do to a person, psychologically, to spend the best part of seven decades on their own in the wilderness? How would their body come to know and relate to the land around them? This book is a result of Willett building a relationship with a man he never knew, and years spent mining Plummer’s almost-lost, barely heard voice from objects and archives. Where he hasn’t found that voice, he’s left us searching.

In the same New England area some years after Plummer retreated, Ralph Waldo Emerson and the Transcendentalists would rise to prominence, with their beliefs that people are truly at their best when independent and entirely self-reliant – “intuition over empiricism”. The landscapes in this area of the world hold something enigmatic and elegiac for thinkers, and in the Disappearance of Joseph Plummer, Willett has tangibly managed to distil that, feeling his way through a story that has left barely any clues with such sensitivity. The same figure we see at the beginning of the book recurs throughout it: black and white, blurred, face bleached out, sometimes in almost pitch blackness – there’s always something removing it from reality. The whole landscape as Willett offers it to us is achingly full of solitude. Where water is depicted it’s deathly still – as if taken in those last moments of perfect, wild silence just before dawn. The woods are dark and impenetrable, thick and obscuring, like they would swallow a person whole. At other times, signs of life, houses and cabins, filter in slowly, as though seen by someone somnambulating past. Willett layers different types of images into the book, working and reworking them and experimenting with them in an intuitive sort of way, as if making sense of how he can use photography and images to tell stories, while simultaneously working his way through the land his family owns and making sense of that too. In every sense, this is Willett navigating his own, unmapped territories. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist and Overlapse. © Amani Willett