Photobook Conversations #3 | Miguel Del Castillo: “Books are meant to be touched, seen and flipped through”

Photobook Conversations is edited by Ana Casas Broda (Hydra + Fotografía), Anshika Varma (Offset Projects) and Duncan Wooldridge (Manchester Metropolitan University). Sitting alongside the earlier Writer Conversations (1000 Words, 2023), edited by Lucy Soutter and Duncan Wooldridge, and Curator Conversations (1000 Words, 2021), edited by Tim Clark, it completes the series exploring the ways our understanding and experience of photography is mediated through exhibitions, writing and publishing.

Miguel Del Castillo | Photobook Conversations #3 | 21 Nov 2024

Miguel Del Castillo is a writer, translator, editor and curator. He was born in Rio de Janeiro and lives in São Paulo, Brazil. Named one of the best young Brazilian novelists by Granta, he is the author of Restinga (Companhia das Letras, 2015) and Cancun (Companhia das Letras, 2019). He coordinates the Photography Library at Instituto Moreira Salles (IMS) in São Paulo and was formerly Editor at Cosac Naify and ZUM magazine’s website. Del Castillo previously published an online column on photobooks and is now pursuing an MA in Literary Theory at the University of São Paulo.

What were the encounters which started your relationship with photobooks?

I began my career at Cosac Naify, an art and literary publishing house, where I started as an intern before being hired as an Assistant Editor for children’s books. After a few years, I also began assisting with architecture and art books, as well as handling image rights. Eventually, I had the opportunity to become a full editor, overseeing both architecture and photography books. I had the opportunity to work on books by notable Brazilian artists such as Bob Wolfenson, who, in Belvedere (2013), explored a series quite different from his renowned work in fashion, focusing instead on photographs of decaying tourist spaces. With Vicente de Mello, I collaborated on Parallaxis (2014), which brought together several of his series. Our aim was to create something that felt less like a catalogue and more like a photobook – a reflection of his life and artistic journey. I also worked on Contrastes Simultâneos (2014) by Walter Carvalho, whose photographs in the book closely echo his acclaimed work as a cinematographer.

At this stage, my studies in architecture, combined with my interest in photography and experience with art books, played a crucial role. Additionally, my work with children’s books honed my sense of sequencing, and my ability to handle image-text relationships and page transitions which are vital in photobook editing. In fact, I believe photobook studies could benefit significantly from the theory and criticism that surrounds children’s books. Following my experience in publishing, I was invited to join Instituto Moreira Salles (IMS), which was then developing a new museum in São Paulo. I was tasked with leading the Photography Library, building its collection from the ground up, and developing public programs centered around photobooks.

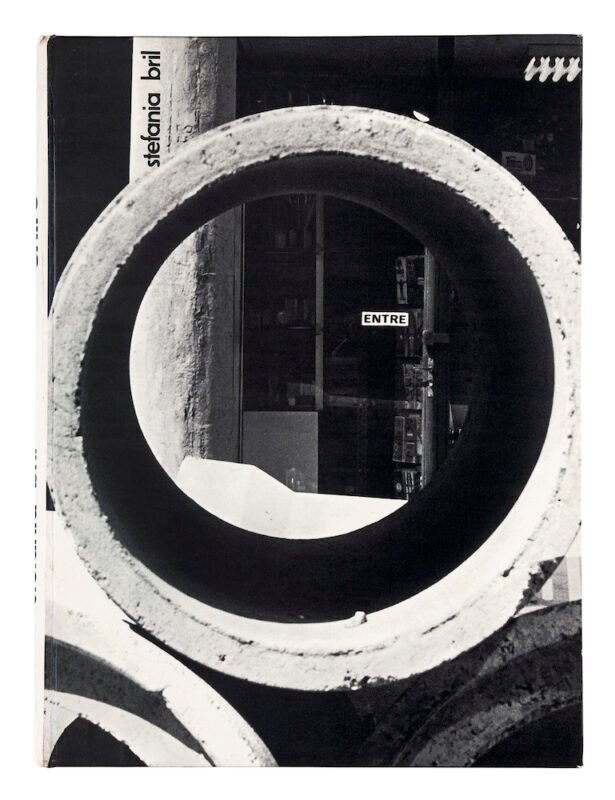

To kick off the collection, we first established our priorities: the primary focus would be Brazilian photography, followed by Latin American, and then international works. Our aim was to gather as many photo-publications as possible from Brazil, while being more selective with foreign acquisitions. We already had some books that were purchased for curatorial research, as well as the Stefania Bril collection – around 1,000 books which demonstrate her important role as an articulator of the photographic circuit in the country, with an eye in tune with the international production of her time (the 1970s and 80s). From there, we formed institutional partnerships, established contacts with national publishers to acquire more books, and purchased several private collections from key Brazilian figures, giving us a solid foundation to build on.

What is your process for arriving at decisions about books and the projects that you undertake?

I strive to think beyond a niche, especially when developing public programmes around photobooks. In São Paulo, there are many specific initiatives that are valid and interesting, but I aim to foster interest among a broader audience. At the IMS library, we have a dedicated space for photobook exhibitions, and I curate selections that appeal to the general public. For example, at our opening in 2017, I presented an exhibition titled São Paulo in the Photographic Book: 1954–2017, which aimed to highlight, through books, the city’s inequalities and rapid, ongoing transformations. Subsequent displays have included a focus on books about military dictatorships in South American.

Previously, at the publishing house, I was fortunate to work closely with in-house graphic designers. This setup is somewhat rare, especially in Brazil, where the editorial team is typically fixed, and graphic work – like covers or the entire design – is usually outsourced to external collaborators. Having graphic designers integrated into the team from the very start of a project was a real advantage. We were able to discuss ideas from the initial concept phase, make adjustments throughout the process, and refine every detail all the way to the final product. This close and continuous collaboration between the designers and the editorial team was a powerful catalyst for the book-making process. The ability to brainstorm, revisit decisions and fine-tune both the visual and editorial elements together made the creative process much more dynamic and cohesive. It allowed for a seamless exchange of ideas, resulting in books that were more thoughtfully crafted from both an editorial and design perspective.

What is the public for a photobook? Who do you think of as your audience?

Being a non-librarian heading a library has significantly shaped how I approach this question. I greatly benefit from my team (including librarians), who offer valuable perspectives on book culture and knowledge sharing. First, what does it mean to create a library dedicated to photography, with photobooks at its core? For us, it means expanding a specific audience and democratising access to photobooks. We achieve this not only by having quality books available but also by fostering an open, welcoming space without membership cards or access restrictions – some visitors even come to work on their own projects. We provide direct access to shelves and promote talks, study groups, book exhibitions and thematic selections.

As editors, we may not always consider how to distribute our books through libraries. Early in the IMS library’s journey, artist Rosângela Rennó gave a lecture in which she said something that has since become our guiding principle: “Photobooks are how we’ll explain what photography was to future generations. We must fill libraries with them; they cannot be confined to private collections.” When I talk to editors now, I try to convey this idea. It doesn’t have to be our library, but it could be their local library or the museum library near their home. To condense this into one sentence: I believe the audience for photobooks is still quite limited, but libraries offer a powerful way to broaden it.

How important is it for photobooks to reach other continents?

I believe it’s essential for the general public to have access to books from diverse places and cultures, as much as possible. At the IMS library, our priority is Brazilian books – we aim to collect everything published locally to preserve our photobook culture. However, we also include foreign books in our collection. When we started, we acquired private collections built between the 1980s and 2000s. Only later did we realise that most of the foreign books were from North America and Europe, as those were the main references and the ones available for purchase here. In response, we made a concerted effort to acquire more books from Latin American, African and Asian authors for our archive. This required active research and engaging in discussions with scholars and researchers who specialised in these regions. We also had to recognise that, even today, many voices from outside North America and Europe are still being published by presses within these continents. Acquiring books published locally in places like Africa, for instance, remains a particular challenge due to issues such as limited distribution channels and prohibitive shipping costs. Navigating these barriers has been an ongoing effort, but it’s essential for ensuring that our collection has the broadest representation of voices.

I can’t speak directly for authors regarding how it impacts them when their books are recognised or showcased abroad, but personally, if I were to publish a photobook, I’d love to know that it was being seen in a library in Mexico, Japan or elsewhere in the world.

What do you think is the significance of the shift towards the book as an object?

There is something in this idea that started to bother me, especially while establishing the library at IMS and developing our access policies. While it is indeed important to recognise the photobook as a three-dimensional object with unique qualities, I’ve found that this perspective can sometimes lead to treating it as an untouchable work of art. At IMS, we decided to keep most of our books accessible on open shelves for the public to browse. Just because a book might cost $300 from an online reseller (due to multiple speculative reasons), it doesn’t mean it should be kept away from users.

If one of the main ideas behind creating a photobook is to provide a more accessible experience than a traditional reproduction, then it doesn’t make sense to publish it only to confine it under a glass dome, where people can see only the open spread or, at best, view a video of it. Of course, there are exceptions for older, more fragile books that require special handling or artist books produced as unique editions. But in general, I advocate against the unnecessary sanctification of photobooks. Books are meant to be touched, seen and flipped through; they should be accessible for people to engage with and share.

What is the place of language and writing in a book of photographs?

As a writer myself, I have a particular appreciation for books that balance writing and images, where both elements complement, provoke or even contradict each other. I’m not referring to photobooks that include a preface or postface (although those can be valuable), but rather to books where text and images are intertwined more deeply, such as El infarto del alma (1994) by Chilean photographer Paz Errázuriz and writer Diamela Eltit, or the Brazilian classic Paranoia (1963) by poet Roberto Piva and photographer/graphic designer Wesley Duke Lee. Contemporary examples also abound, with specific categories even created for this kind of work, such as in the Arles Book Awards.

Maureen Bisilliat, an English-Brazilian photographer, offers a compelling approach with her series of books that pair extracts from renowned Brazilian writers (like Guimarães Rosa, Jorge Amado and Adélia Prado) with her own photographs, creating new narratives she terms ‘photographic equivalences’. She challenges the cliché that “a picture is worth a thousand words” by asserting that her photographs are only complete when paired with text. I once curated an exhibition about this aspect of Maureen’s work, which I called Writing with Images and Seeing with Words, a quote of her own. This perspective adds a rich layer to the discussion of photo-text books.

I also believe there’s much to learn from children’s book theory in this context. For instance, Sophie van der Linden’s Lire l’album (2006) notes that: ‘In picture books, texts and images sometimes ignore each other, contradict each other… But they cannot be compartmentalised or separated completely. Present together in a single space, that of the double page, they are apprehended by the same gaze and necessarily relate to each other from a formal point of view. It is therefore a question of appreciating the occupation of space by these two languages, their own characteristics, their arrangements, the effects of resonance or contrast… Considering that, at the formal level alone, there are already countless implications in terms of narrative and discourse.’

Who have been the models or templates for your own activities?

Before the opening of our library in 2017, I extensively researched various art and photography libraries around the world for inspiration. The first ICP Library was definitely one of them. I was also particularly intrigued by Stiftung Sitterwerk’s advanced system for digitally emulating book shelves, which uses a robotic scanner to recreate book spines side-by-side. Although such a system could be valuable for remote users, what I learned from their effort was the importance of allowing visitors to physically interact with shelves, and that’s exactly how we decided to approach our own library policy. There’s something uniquely rewarding about browsing freely and stumbling upon a book you weren’t specifically looking for alongside one you were. We also drew from independent initiatives like TURMA in Argentina, which has developed a library and a space for courses and activities, as well as other Latin American institutions such as Mexico’s Centro de la Imagen and Uruguay’s Centro de la Fotografía (CdF), with whom we continue to stay in touch.

In terms of publishers, Steidl has been a key partner from the beginning. Gerhard Steidl’s significant impact on photography publications since the 1990s is well recognised. He also decided to collaborate with us to host the first Steidl Library, which includes a complete set of his publications generously donated to us.

What’s currently on your desk?

I have the privilege of working in a room adjacent to the library, which means that each time I go to the bathroom, I cross a long corridor lined with tall bookshelves filled with photography books! This constant visual presence is quite stimulating.

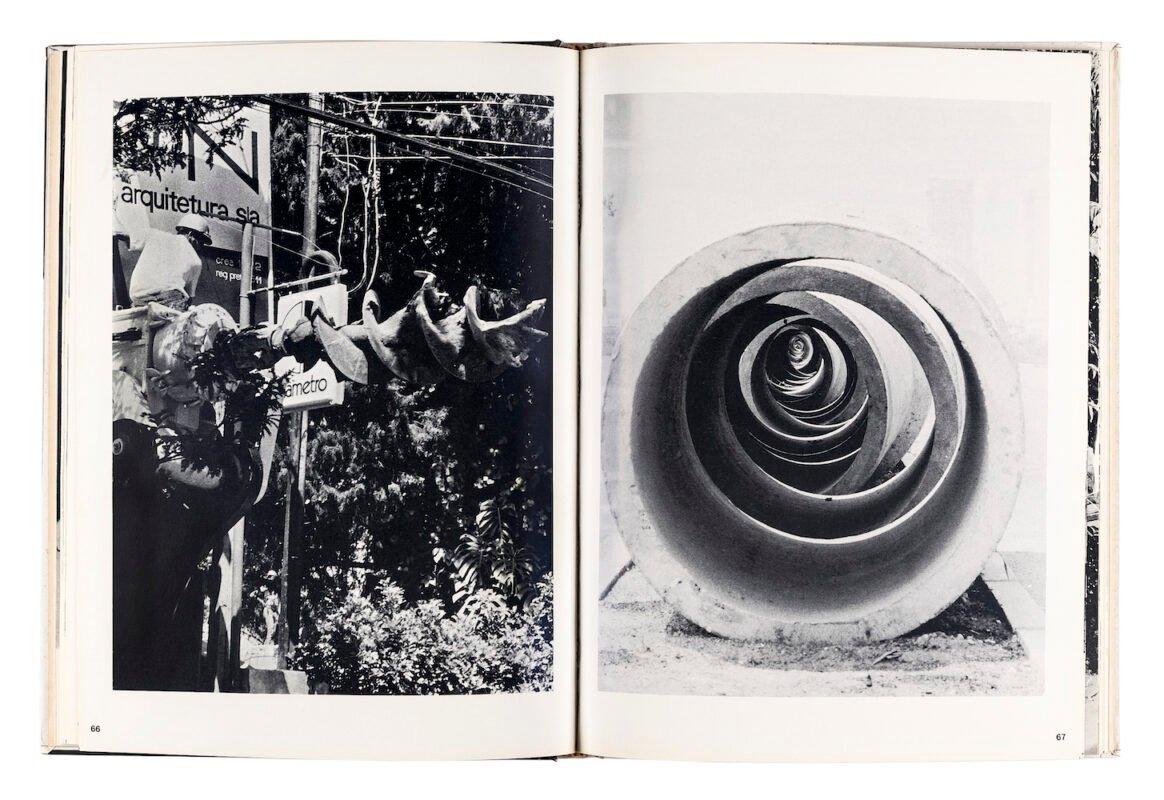

Recently, I’ve had two Brazilian photobooks on my bedside table. One is Sete Quedas by Shirlene Linny and Júlio Cesar Cardoso (2020), an in-depth visual investigation into the story of a brutal kidnapping and murder of an ambassador during Brazil’s military dictatorship. The other is República das Bananas (2021), a strange and brilliant fiction created by Shinji Nagabe. Additionally, I had been frequently revisiting Entre (1974) by Polish-Brazilian photographer Stefania Bril, as I have been working on her major exhibition, entitled Stefania Bril: Desobediência pelo afeto [Disobedience through Affection].♦

Further interviews in the Photobook Conversations series can be read here

Click here to order your copy of the book

Images:

1-Miguel Del Castillo © Carolina Ribiero

2>3-Stefania Bril, Entre (Self-published, 1974)

4-Photography Library at Instituto Moreira Salles (IMS), São Paulo © Pedro Vannucchi

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique and activism

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous Dahmani

• Shana Lopes reviews Agnieszka Sosnowska’s För

• Valentina Abenavoli discusses photobooks and community

• Michael Grieve considers Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler’s posthumous collaboration with their late family member

• Elisa Medde on Taysir Batniji’s images of glitched video calls from Gaza