Luigi Ghirri: Viaggi

MASI Lugano

Interview with Curator, James Lingwood

Luigi Ghirri: Viaggi. Photographs 1970–1991 is a major exhibition dedicated to the Italian photographer Luigi Ghirri running at MASI Lugano, Switzerland, until 26 January 2025. Featuring 140 colour photographs – primarily vintage prints from the 1970s and 1980s – sourced from both the artist’s estate and the CSAC collection in Parma, the exhibition underscores the role of travel in Ghirri’s oeuvre. An accompanying book, co-published with MACK, situates Ghirri’s photography within both Italian and international contexts, marking his unique relationship with image-making and visual culture. In a conversation with Editor in Chief Tim Clark, curator James Lingwood discusses the making of the exhibition, Ghirri’s playful and reflective approach to photography, his distinctive use of colour, and how his work subtly critiques the impact of mass tourism on the medium.

Tim Clark | Interview | 14 Nov 2024

Tim Clark: Do you remember your first encounter with the work of Luigi Ghirri?

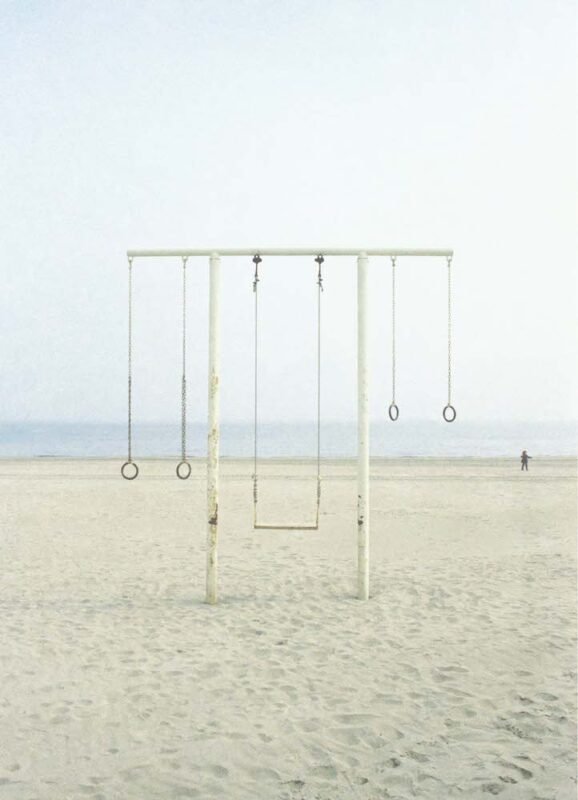

James Lingwood: Coming across Ghirri’s first book, Kodachrome published in 1978 was a revelation. It has many memorable individual images, but what is really remarkable is its orchestration, the undulating rhythms of the book. It’s not a coincidence that the very first image in the book is of a cloudy sky, with several horizontal lines running across – like a page of sheet music without the notations. Then at the Venice Biennale in 2011, there was a group of Ghirri’s photographs in the main exhibition in the Italian Pavilion, including some he made on the Adriatic coast, with a children’s swing or carousel on an otherwise empty expanse of beach and the horizon line behind. Or it may have been the other way round…

TC: Tell us about the impetus for this show at MASI following the retrospective The Map and the Territory exhibition that toured Museo Nacional de Arte Reina Sofia, Museum Folkwang and Jeu de Paume from 2018–2019 that you curated. How did you want to build on that previous proposition through this notion of ‘the journey, as idea and image’ as a point of emphasis?

JL: The Map and the Territory exhibition was put together to foreground Ghirri’s singular way of thinking about his work, to show how reflective, poetic and also playful it is. I decided to work with the structure of the most important exhibition of his work in his lifetime, Vera Fotografia which was presented in Parma in 1979. Ghirri presented 14 different groups of photographs in the exhibition. It’s important to say that Ghirri considered the group as a work; he used the words interchangeably. Some works had a tight conceptual framework, such as Atlante, a series of photos of close-up details of pages from his atlas, or ‘∞’ Infinito, a grid of 365 photos of the sky, taken every day through 1974. Other groups, (or works!) such as Kodachrome, Diaframma 11, 1/125, Luce Naturale, or Vedute were much more open. The Map and the Territory reprised this structure, and its focus on the first decade of Ghirri’s photography, up to 1979.

Viaggi grew out of the earlier exhibition and develops some of its themes through the prism of the journey. The journey resonates throughout his work; not only because almost all his photographs were made on trips of various kinds, but also because he considered photography to be a ‘journey through images’. It’s implicit in The Map and the Territory, and made more explicit in Viaggi. For example, the selection of photographs from his series Paesaggi di Cartone and Kodachrome concentrates on images of travel and tourism ‘found’ in the urban landscape. There are important groups of photographs from other series such as Diaframma and Vedute which are central to Ghirri’s exploration of the act of the viewing.

In both shows, it was impossible not to give a prominent space to two important works, to the speculative journeys prompted by the close-up images of details of his atlas in Atlante, and Identikit, Ghirri’s take on Xavier Le Maistre’s novella A Journey around my Room, a group of photographs of the books, LPs, maps and mementoes in his home.

The selection for Viaggi ranges widely across his work from the 1970s and 1980s, and extends to groups of photographs made on Ghirri’s travels to different parts of Italy, both to tourist destinations like Rome, Venice, Naples and Capri, but also to places off the beaten-track, small towns and cities in Puglia or Emilia Romagna. It is more open than the earlier exhibition.

TC: One thing that is clear about the curation here is the fairly fluid layout as opposed to a fixed structure. This allows visitors to seek out connections and consider how travel guided Ghirri to subjects and places. How did you approach this creative aspect of putting together the show? It seems very redolent of Ghirri’s adage that ‘if photography is a journey, it is not so in the classic sense suggested by this word; it is rather an itinerary that is drawn, yet with many diversions and returns, randomness and improvisation, a zigzag line.’

JL: If photography is a journey, so is an exhibition. I love the idea of the zig-zag line, with different routes through the work rather than one prescribed route. I don’t think it helps to present Ghirri in too linear a way, with extended sequences of images on long walls. So we broke up the space at MASI with a smaller walls to create a more open structure, and to offer different pathways through the work. When you reach the ‘end’ of the exhibition, you need to move back through the same spaces, seeing different perspectives and making different connections.

TC: In your catalogue essay, you summon the words of Arturo Carlo Quintavalle, Ghirri’s friend and interlocutor – who himself was so instrumental to building discourse around photography in Italy from the 1970s onwards – from a small text that accompanied Ghirri’s images in La gita from Enciclopedia pratica per fotografare (1979): ‘The photographic ritual is the ritual of the trip, there is no trip without photography, without adjusting the aperture and recording [the scene … Ghirri’s] research begins with planning, with a trip seen in images, with the map of mountain paths in perspective, and gradually follows different familiar routes, in the mountains, at the seaside, at lakes, and in the city.’

This particular framing of Ghirri’s work suggests a critical reflection on photography’s vital contribution to industrial societies becoming “image junkies” or “modern” (in Susan Sontag’s sense of the word), where consumption and excess built a status for the photographic image beyond that of mere document. How does Ghirri’s work represent a profound shift in the culture of his time, and ours now?

JL: Ghirri sensed the shift and in some of his work, he consciously pictured it. He could see that as the activity of taking photographs, especially on holiday, was becoming commonplace, it was having a profound effect on the experience of the places people travelled to. He thought a lot about the impact this was having on modern culture. However it’s a big jump to today’s “image junkies”. The consumption of images in Ghirri’s time was moderate compared to today’s excesses. He was critical, but he was not harsh.

TC: You’ve also previously mentioned that Ghirri intentionally positioned his work in ‘proximity to the amateur’ through his distinctive use of tonal range and colour. How would you describe the way colour functions and matters in his photographs?

JL: Ghirri did to some extent side his work closer to the amateur, and to popular and vernacular culture, and away from the approach and look of the photography professional.

Certainly most ‘serious’ photographers in the 1970s favoured bravura black-and-white prints of their landscapes, portraits or still lives. Documentary photography was predominantly black-and-white. Colour was for advertising, for popular magazines. It was at the margins of the serious photography world whilst in the late 60s and early 70s, but at the same time it was of interest to artists like Ed Ruscha. John Baldessari or Dan Graham, or closer to home Franco Vaccari who embraced the vernacular.

Working in colour was a key decision that Ghirri made right at the beginning, in 1970. In his first piece of published writing, he stated: ‘I photograph in colour because the world is in colour, and because colour film has been invented.’ The film he used through the 1970s was almost always Kodachrome – the same film millions of people would take to be processed in a lab when they got back from their trip. Ghirri did the same, taking his films to a processing lab in Modena. But there is a difference, an important one, both in the type of images he took and their colour. He wasn’t interested in eye-catching effects, whether through dynamic framing, dramatic incident or sharp colour. He was interested in a quieter, more reflective image and he worked closely with Arrigo Ghi, who made the prints in Modena, to develop a tonal range which was in keeping with the quietness of his images. Ghirri’s skies are instructive. The light is often even and flat, and the blue is rarely vivid.

TC: To what extent does Ghirri adopt or eschew the iconic tourist photo?

JL: There are a few if any photos that Ghirri made that simply adopt the iconic tourist view. But he’s very aware of the types of photos that tourists were taking, the stereotypes of postcards, advertising and the like. In 1973 he wrote that when he travelled, he took two kinds of photographs; ‘the typical ones that everyone takes… and then the other ones, the ones I really care about, and the only ones that I really consider “my own.”’ Whereas the tourist image tends to conform to type, Ghirri’s photographs both recognise and diverge from it.

TC: In what ways do you feel Ghirri harnesses and pushes back against the ‘decisive moment’ across some of his different series, let’s say if we compare the overarching concerns of Diaframma 11, 1/125, luce naturale with Vedute?

JL: Decisive moments in photography generally need people and they need movement. There is very rarely any movement or incident in Ghirri’s photographs, and there aren’t many people. When they are present, they are seen from a distance, or from behind, quietly looking at something (a map, a painting, a display in a shop window) or taking in the view. What was important for Ghirri was not so much a moment in time as its distillation.

TC: Can you say something about your own personal journey through Ghirri’s archive? For example, are there any particular pairings of individual images and their resonances that you relished either putting together or recreating in the show?

JL: Spending time with Ghirri’s work feels like being in a story by Calvino which never ends, and which leads you to many different places, some recognisable, and others new. Ghirri delighted in playing with the vast repertoire of possibilities his archive offered and I feel his sense of adventure through a world of images gave me the licence to work in the same spirit, discovering new resonances as well as revisiting familiar. Some of the pairings in Viaggi are straight out of the pages of Kodachrome, like the photo of a tourist from Paris holding a little souvenir of the Eiffel Tower paired with the model Eiffel Tower in a theme park in Rimini. Others were improvised whilst installing the show. Hopefully this makes the journey full of discoveries, diversions and returns…♦

All images courtesy Estate of Luigi Ghirri, MACK and MASI Lugano © Estate of Luigi Ghirri

Luigi Ghirri:Viaggi. Photographs 1970–1991 runs at MASI Lugano, Switzerland, from 8 September 2024 – 26 January 2025, with an accompanying catalogue published by MACK.

–

James Lingwood is a curator, producer and writer, based in London. From 1991–2023 he was Co-director of Artangel with Michael Morris, producing over 150 new projects by artists, choreographers, composers, filmmakers, and writers.

Tim Clark is Editor in Chief at 1000 Words and Artistic Director for Fotografia Europea in Reggio Emilia, Italy, together with Walter Guadagnini and Luce Lebart. He also teaches at The Institute of Photography, Falmouth University.

Images:

1-Luigi Ghirri, Rimini, 1977.

2-Luigi Ghirri, Alpe de Siusi, 1979.

3-Luigi Ghirri, Marina di Ravenna, 1986.

4-Luigi Ghirri, Rifugio Grosté, 1983.

5-Luigi Ghirri, Scandiano, presso la Rocca di Boiardo, 1985.

6-Luigi Ghirri, Modena, 1973.

7-Luigi Ghirri, Versailles, 1985.

8-Luigi Ghirri, Capri, 1981.

9-Luigi Ghirri, Marina di Ravenna, 1972.

10-Luigi Ghirri, Arles, 1979.

11-Luigi Ghirri, Lago Maggiore, 1984.

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique and activism

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous Dahmani

• Shana Lopes reviews Agnieszka Sosnowska’s För

• Valentina Abenavoli discusses photobooks and community

• Michael Grieve considers Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler’s posthumous collaboration with their late family member

• Elisa Medde on Taysir Batniji’s images of glitched video calls from Gaza