The unseen effects of illness

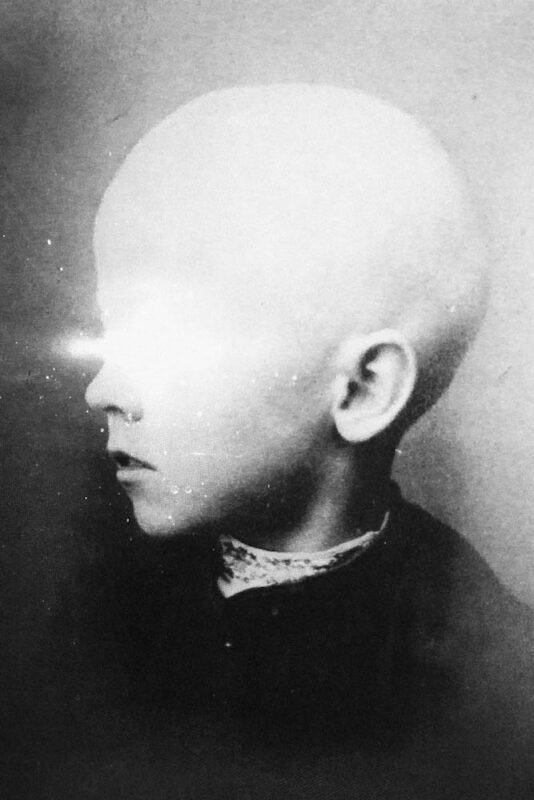

Worry for the Fruit the Birds Won’t Eat is Sophie Gabrielle’s visual investigation into the unseen effects of illness. Responding to the emotional toll of all the male members of their family being diagnosed with stage IV cancer over two years, the artist employs optics, chemical interactions and investigative photography to render the invisible. Thomas King speaks with the winner of OD Photo Prize 2024 about the project and its deeply personal starting point.

Thomas King | Interview | 17 Oct 2024

Thomas King: Worry for the Fruit the Birds Won’t Eat, recently announced as the winner of OD Photo Prize 2024, features various images of early phototherapy practices, such as UV light exposure and ‘light baths’ used on children, alongside early X-ray experiments. How would you discuss your relationship with the archive in the context of this project? And what was the motivation to create a dialogue between the historical and the personal?

Sophie Gabrielle: I have always been a collector of images. From a young age I would cut pictures out in magazines for safekeeping. The use of scientific archive photography in my work began in university when I based the series BL_NK SP_CE on an MRI scan. Using archive photography relating to X-ray and UV exposure started during a period of research into my father’s stage IV cancer diagnosis. Wanting to understand what was happening, I came across an initial X-ray image and the collection began.

I felt drawn to these archive images after discovering that many of these initial experiments into ionising radiation (x-rays) and UV light baths were cancer-causing. There was this duality to them, experimentation into science that would eventually help treat my family and the initial causation of illness for those in the photographs themselves. During this period of time, I was documenting my family, photographing our lives as we went through this sudden upheaval. However, the images felt too personal to show, they became my secret garden. Using the archive, with its scientific detachment, allowed me to create a public dialogue about my experience while still maintaining a sense of privacy for my family. This project has let others share their own experiences of cancer with me, creating deep felt connection of both loss and joy.

TK: This series involves an intricate process of capturing and re-photographing images under glass plates. What challenges or unexpected discoveries did you encounter during this process, and can you comment on the way they influenced the final outcomes of your work?

SG: There were two main challenging points – touch and light. Handling the plates of glass was always tricky. Initially, I was focused on trying to only capture dust but my fingerprints, hair and fibre would interfere. Over time though I began to appreciate their presence in the works. They were uncontrollable parts of human existence, and ultimately that was a large part of the work.

Light was the other, the most controlled part of the works. Angling both flash and continuous light on specific parts of the photographs was laborious. This control was so important to the works, freezing time for a moment – something I could decide when, how and what it was doing in a time that felt so opposite. The interplay of control and accident in both light and touch ultimately shaped the tone of the final images.

TK: You’ve previously described the investigative processes involved in photographing worlds invisible to the naked eye. In your work, light seems to dissolve and mystify reality – what did you intend to conjure?

SG: In all my work, I aim to convey the tension between visibility and invisibility and the power of the photograph as an object with a duality of truth and lie. They seek to represent the complexity of something deeply felt yet difficult to fully articulate. Through abstraction, I create space for viewers to engage with the work on their own terms. By distorting the clarity of the image, I invite a more nuanced and subjective reading of illness and existential fragility. This approach allows my audience to explore the emotional landscape in ways that reflect their own experiences, emphasising the ambiguity and intricacies of human vulnerability. I’m particularly interested in what is missing in a photograph, what is left out and what we ultimately search for. What makes an image relatable, is what draws us in and creates tension.

TK: In your artist statement, you refer to the project as a form of self-portraiture through abstraction. How do you view the role of aesthetics in conveying personal trauma or existential themes?

SG: We live in a time where there’s an expectation to share our lives and identities in a digital, public way. I see art as fulfilling two essential roles: expressing the artist’s experience while also allowing space for the viewer to connect and interpret it in their own way. Aesthetics play a crucial part in this and through my methods I can engage with personal trauma without being overly literal, which mirrors the non-linear, fragmented nature of emotional processing. Rather than just communicating one perspective, the visual language in my work creates room for reflection on resilience, growth, and the inevitable changes we all undergo. It’s about offering both the artist and the viewer a way to connect deeply, yet individually.

The dust, made up of skin particles, connects the body and environment in a subtle way, entwining living presence with historical materials. This layering of dust and re-photographing became meditative and allowed me to reflect on the inevitable impact of time. It also connected these experiments to the people who would eventually be helped by them in the future. In this way it became self-portraiture, as I was a part of this process, my presence being the creator. I started this work in 2018 so it has been a long process and progression from where I first began. Speaking about this work now, both my grandfathers have passed and I have lost friends from cancer and it still feels just important to share this work, to hold open dialogue and openly grieve.

TK: Michel Foucault’s concept of the ‘medical gaze’ suggests a detached, often objectifying perspective on the body in medical contexts. In what ways does your work confront or complicate this idea, and how does the integration of personal bodily traces affect the perceived objectivity of medical imaging?

SG: I aim to reintroduce subjectivity and emotional resonance, emphasising the personal stories that exist beneath medical images. By transforming archival medical images into personal, poetic narratives, my practice directly engages with the relationship between the body, illness and the scientific gaze. Combining historical photographic processes with environmental interventions complicates this gaze, allowing me to reclaim the narrative of the body and illness. I integrate memory, grief and environmental decay to create something that resonates beyond the clinical sphere, inviting a deeper exploration of what these experiences mean on a personal level. ♦

All images courtesy the artist and Open Doors Gallery. © Sophie Gabrielle

Explore the full shortlist from OD Photo Prize 2024 via Open Doors Gallery.

—

Sophie Gabrielle is a photographer living and working on the lands of the Ngunnawal, Ngunawal and Ngambri people (Canberra, Australia). Their work uses biomaterials, photographic archives and the human body to investigate the connection between photography, history, memory and psychology. Gabrielle has exhibited in Australia, Malaysia, The Netherlands, France, Germany, South Korea, the USA and the UK. Recent commissions and collaborations include The New Yorker: cover art for The Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra and UK musician Seabuckthron’s album Through a Vulnerable Occur. They are a Foam Talent recipient (2018) and a finalist for the Lens Culture Emerging Talent Awards (2016).

Thomas King is Editorial Assistant at 1000 Words and a student on BA (Hons) Culture, Criticism, Curation at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London.

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique and activism

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous Dahmani

• Shana Lopes reviews Agnieszka Sosnowska’s För

• Valentina Abenavoli discusses photobooks and community

• Michael Grieve considers Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler’s posthumous collaboration with their late family member

• Elisa Medde on Taysir Batniji’s images of glitched video calls from Gaza