Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa

One Wall a Web

Book review by Taous R. Dahmani

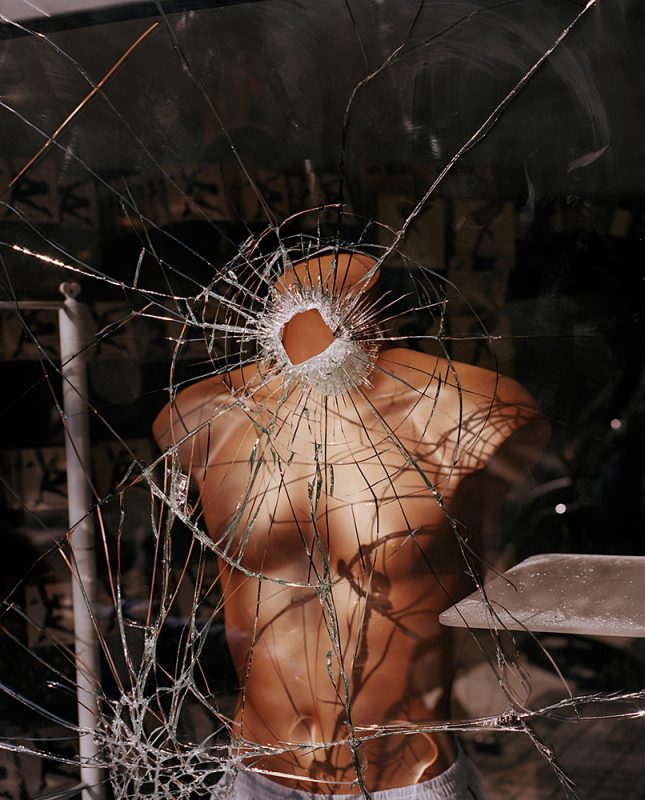

The photograph on the cover of One Wall a Web is a close up of a brick wall. If it seems to block access, as an attempt to establish a border, Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa’s book quickly turns out to be an invitation to deconstruct, brick by brick. He invites us to observe the physical and mental dismantling of racial and gendered violence as it is expressed and experienced in United States society today. Driven by the author’s impulse to tear down this wall so that, once the book is finished and closed, we find ourselves facing two abandoned bricks. Taking the metaphoric nature of these bricks as a point of departure, we might explore the forms of Wolukau-Wanambwa’s discourse through the prism of the poetics and politics of a renewed and contemporary western tradition of scrapbooking.

At first glance unsettling as a result of the multiplicity of narrative strata, leafing through One Wall a Web makes it possible to understand that the story is told both through the photographic image and by the text. Though designed in collaboration with graphic designer Roger Willems, the reader is clearly invited into Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa’s thoughts and state of mind. Professor in the English department of New Jersey City University and historian of the scrapbook, Ellen Gruber Garvey wrote in her 2015 article Homemade Archives: ‘Each scrapbook is a window into the life and thoughts of its maker — and into his or her reading habits.’ Reflections, judgments, positions, observations, speculations and imagination form a complex stream of consciousness. The narrative is constructed using associative jumps and analogies. Various chapters punctuate the work but do not break the flow of reverberations and resonances. Such a juxtaposition of sequences of images and texts recalls the rhythm of the films by American film maker Arthur Jafa and in particular his video APEX.

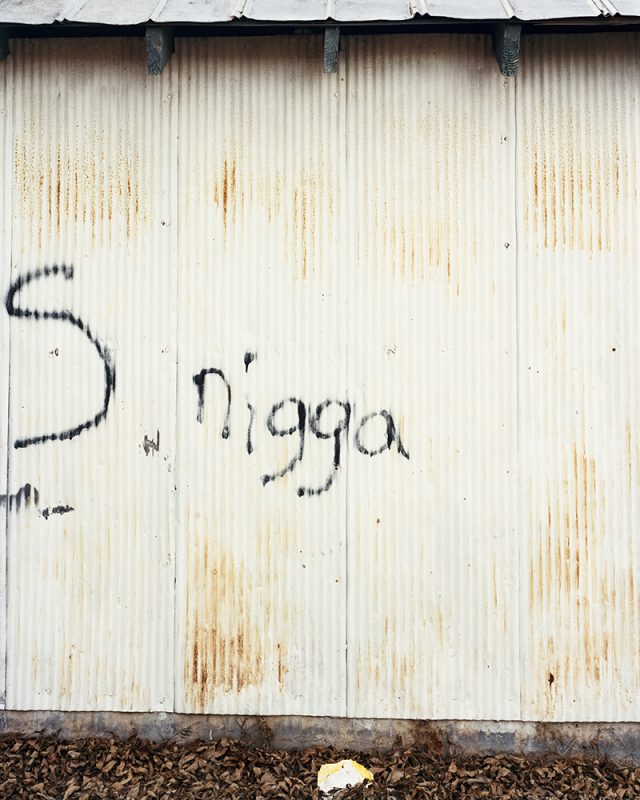

As such, Wolukau-Wanambwa orchestrates an erudite back and forth between quotes from the fascist website breitbart.com, excerpts from Allen Ginsberg’s poems Howl and America, quotations from a Donald Trump interview published in The New York Times and stanzas from Breaking Open and The Speed of Darkness by poet Muriel Rukeyser. These authors, alongside the original and appropriated photographs, are mobilised by the photographer as a network of collaborators and evoke the Rhizome theory as developed by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, (1980), 1987. Texts and images being put on the same level, the work then becomes an evolutionary device that can extend in all directions. Arborescent thinking is opposed to the line of subordination, rooted and taking form, in this case, in the history of structural racism and sexism in the United States. Polymorphic, the rhizome is thus sometimes chaotic, not in its negative sense, but for its capacity of interconnectedness, as Édouard Glissant had it. Linearity and continuum are discarded in favor of fragmentary power.

Successor to commonplace books, popular during Early Modern Europe, where authors could compile their knowledge, usually by writing information in existing books, the scrapbook is a method of textual and visual conservation, presentation and classification that usually offers a meeting point between history and personal narrative. In One Wall a Web, Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa plays around with the possible interweaving between history and current events, in particular by linking his own photographs taken in recent years in Virginia, Alabama, New Jersey and New York, and appropriated archival negatives collected online, printed as positive and displayed as equals to his own images. The range of references used by the photographer-author shows his acute awareness of how history is written and told; regularly shaped by popular culture, journalists, experts, politicians and of course the Internet.

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa’s publication aligns with Pero Gaglo Dagbovie’s statement in Reclaiming the Black Past: ‘Black history is a vital part of contemporary black culture.’ Once he had arrived in the United States, British-born Wolukau-Wanambwa lived and observed the brutality of a society against the black body and inherited the deep scar that is the violent history of African-Americans. Free, radical and sometimes brutal, the verdict proposed by Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa is irrevocable.

Mobilising the tradition of scrapbooks has allowed me to include the photographer in North American storytelling dating back to the Civil War and the Harlem Renaissance. Many pioneering figures must be mentioned: L.S. Alexander Gumby, a queer African-American man, who kept scrapbooks on a wide range of subjects, focusing on black history and black-run newspapers whose critical muscle against the white press is groundbreaking. In his close circle, Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, a Puerto Rican of African and German descent, also made scrapbooks which would become, among other things, the basis for the collection of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem. Another seminal person, Frederick Douglass, known to be the most photographed American man of the 19th century, also kept scrapbooks in order to create a corrective image of race representation. If today this practice seems extremely gendered and depoliticised, for the African-American community, and for these three men, scrapbooks were spaces of the expression of their liberties and their opinions, notably made with cut out newspaper photographs or family albums. Scrapbooks then became volumes that told stories, allowed sharing knowledge widely and as such became a kind of handcrafted archive, validating Jacques Derrida’s statement: ‘There is no political power without the control of the archive.’

Whether in history, or in contemporary proposals, such as that of Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa’s or Clarissa Sligh’s photobook entitled It Wasn’t Little Rock, the meaning of the scrapbook, its poetic range and its political force is thus, in the act of montage and juxtaposition. The cut-up technique, developed by dada artists, and popularised by William S. Burroughs, is based on the idea of making a text from fragments of all kinds. This technique was also used by Burroughs in his scrapbooks, which were visual and textual collages, and tools for prefiguring new ideas for future work. If for Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa and Roger Willems the scrapbook was not a direct source of inspiration for the design of the book, Wolukau-Wanambwa has confided to me the fact that he had been keeping red-fabric scrapbooks for many years. Definitively not a work in progress but a finished object, One Wall a Web, by the combination of his own texts, borrowed words and phrases, his photographs and found images is Wolukau-Wanambwa’s way of recomposing American and African-American history. ♦

All images courtesy the artist and Roma Publications. © Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa

—

Taous R. Dahmani is a photography historian, working between Paris and London. She is a PhD fellow at the Panthéon-Sorbonne University Paris, where she teaches 20th century photography history. In 2019-20, Taous will be a researcher attached to the Maison Française in Oxford. Her thesis project is built around the representation of struggles and the struggle for representation. Her writings and her talks always tackle politics and its relations to the photographic medium.