Amak Mahmoodian

Zanjir

RRB Photobooks / IC Visual Lab

This book intrigues before you even open its cover. Gazing at both its front and back, Persian miniature painting springs to mind. I learn that the cover image is inspired by Mohammad Juki’s illustration made for Shahnameh (1010), the world’s longest poem written by one single poet. This reference frames the poetic character of the book, in which there is a rhythmical and persistent dialogue between the word and image. The book’s title Zanjir, which in author Amak Mahmoodian’s Persian mother tongue means ‘chain’, alludes to metaphorical links between past and present.

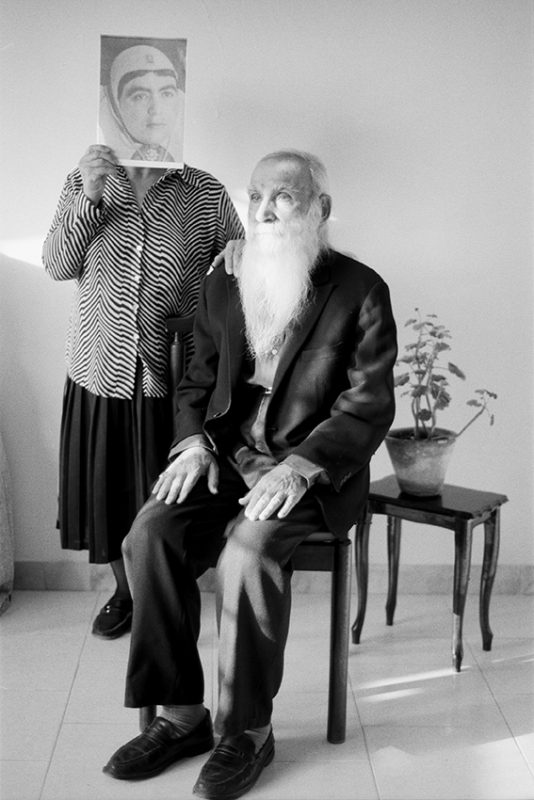

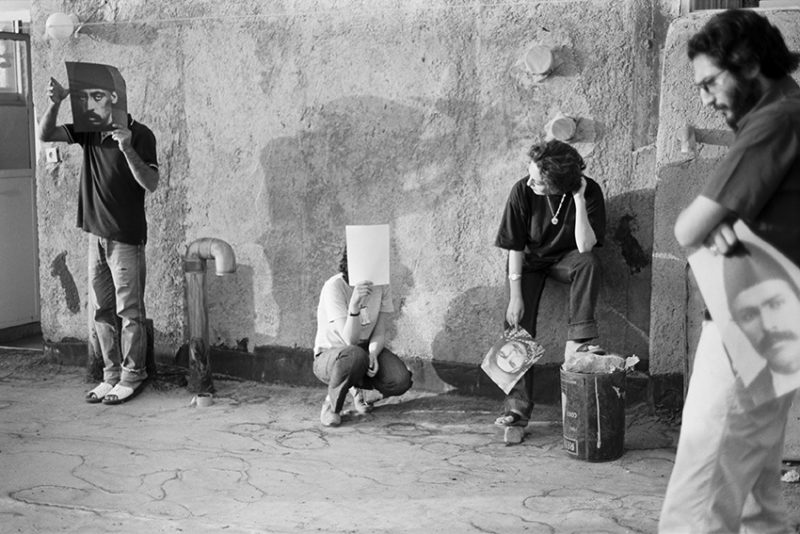

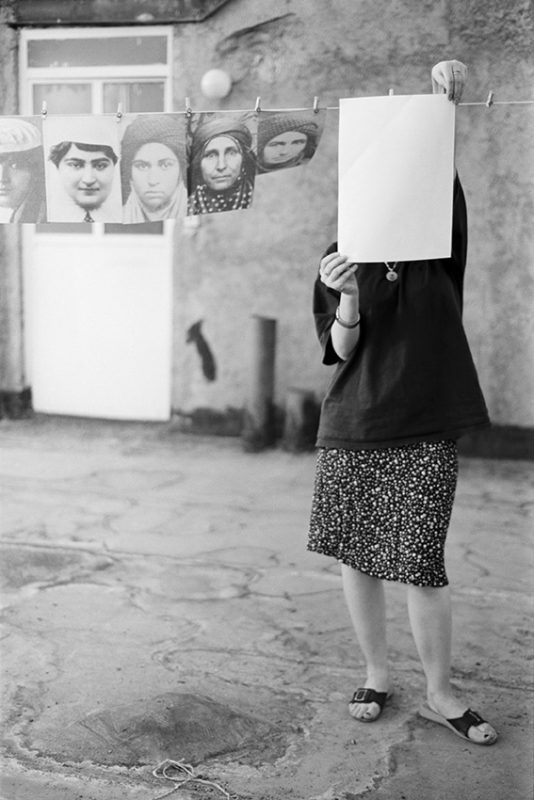

Woven throughout the book are re-presentations of archival portraits taken between 1860 and 1896 sourced from the Golestan Palace Library and Archive in Tehran, Iran, where Mahmoodian undertook an artist residency. Combining this archival material with her own original photography, Mahmoodian generates intriguing relationships between contemporary Iranian culture and its history. For example, four women are in repose in a public park, three are composed for their portrait whilst the fourth turns her back towards the camera – their faces masked by the nineteenth century archival portraits. Observing Mahmoodian’s photographs, Alan Sekula’s 1986 classic writing The Body and the Archive comes to mind, in which Sekula suggests that the territory of information within an archive is revealed by how it is indexed. Through the prism of Mahmoodian’s lens these archival images are re-activated; her sitters perform for the camera, portraits are made and individual identities concealed.

Upon opening this book, the reader enters an imagined conversation between the feminist Persian Princess of the Qajar Dynasty, Taj Saltaneh (1883-1936) and Mahmoodian. Their dialogue continues throughout the book as they lament love, loss and memory. Dividing the book in the middle are a series of elegiac black and red photographs of Mahmoodian’s father on which traces of the poem Shahnameh can be seen tattooed across his body. Through these photographs, Mahmoodian navigates memories of her late father. When photographs cannot convey the depth of emotions captured in them, Mahmoodian’s words offer affective anchorage to the images.

The portrait images are punctuated by the desert landscape, a landscape that holds traces of a human presence yet cannot be geographically located. These photographs are a symbolic reminder that the desert is the only place in which you can see your own shadow. Gazing at these landscapes one’s imagination can breathe. As I reflect on this book I wonder whether it is limiting to refer to it as a photobook, as it calls on both image and text equally to link together lands, cultures, languages and memories. The poetry of words knit together the imagery contained in the book. It is a reflective book that contains a deeply personal narrative which pertains to broader concerns of love, grief and exile, that are tightly held in our hearts. After all, as the Mahmoodian–Saltaneh dialogue suggests: “Isn’t the review of one’s personal history the best undertaking of the world?” ♦

All images courtesy RRB Photobooks / IC Visual Lab. © Amak Mahmoodian