Doug Rickard

N.A

Special book review by Gerry Badger

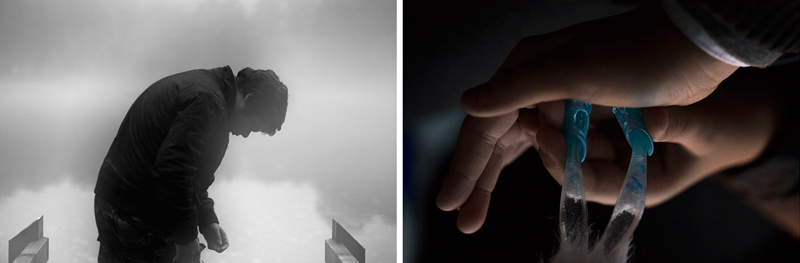

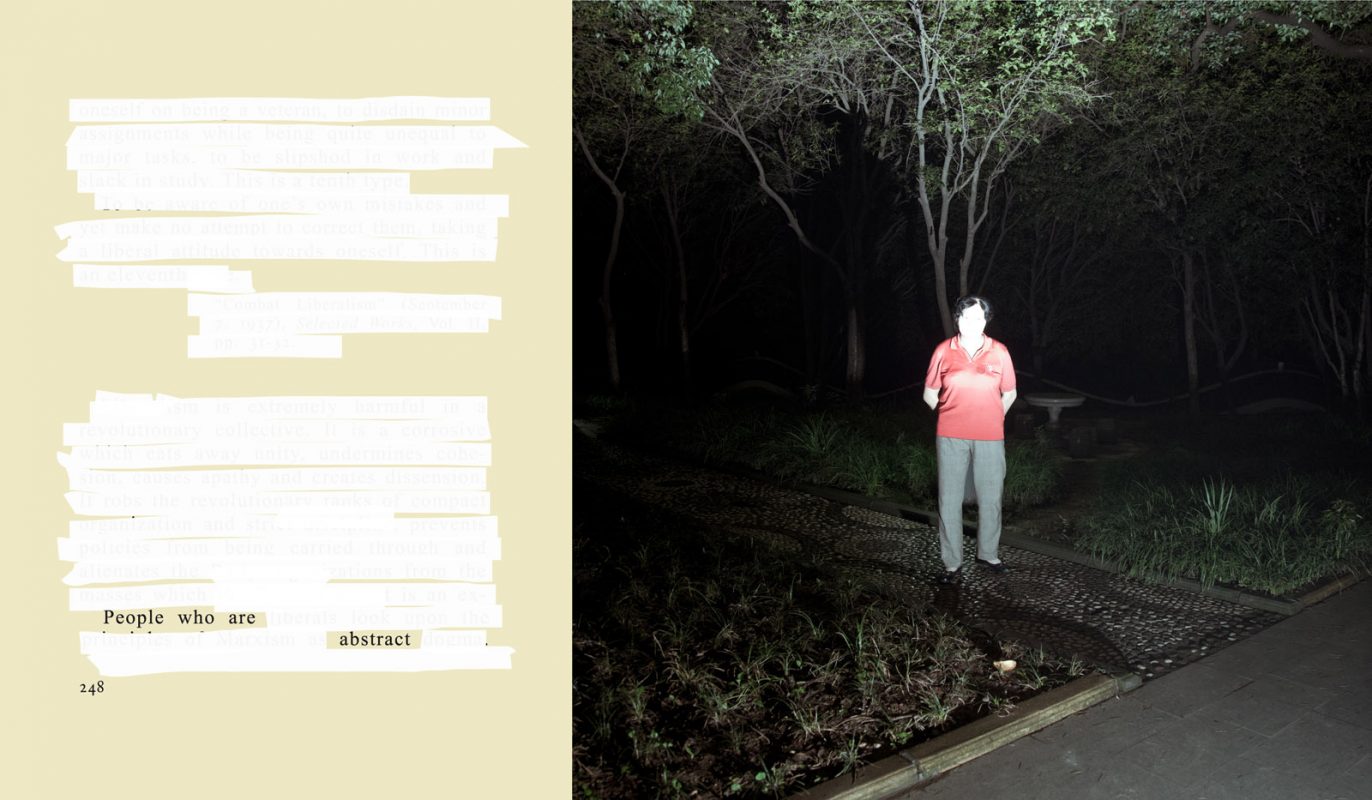

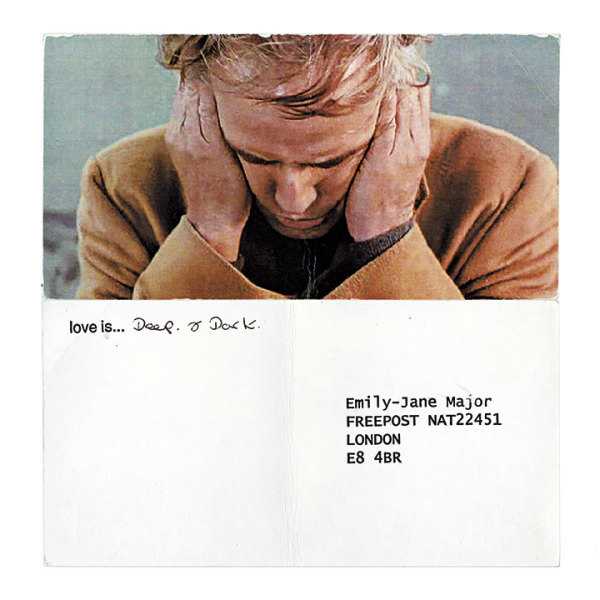

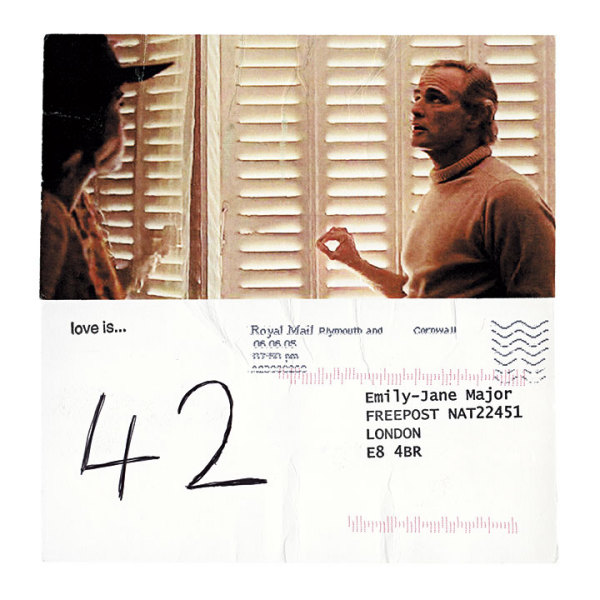

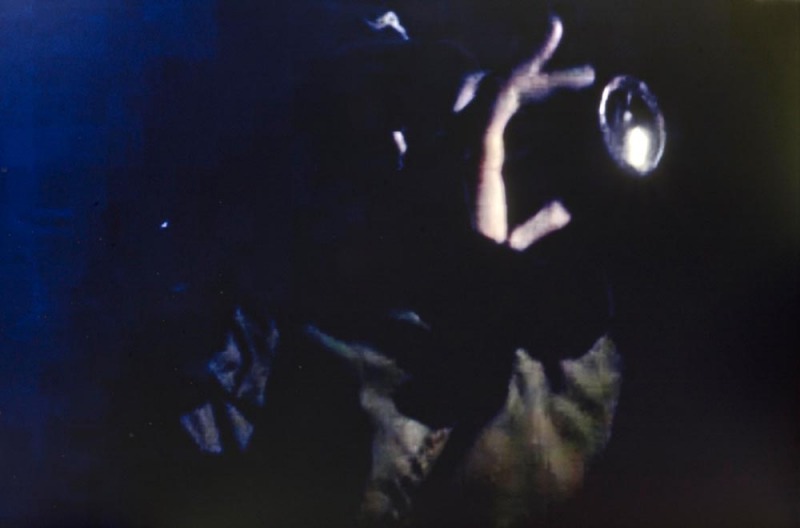

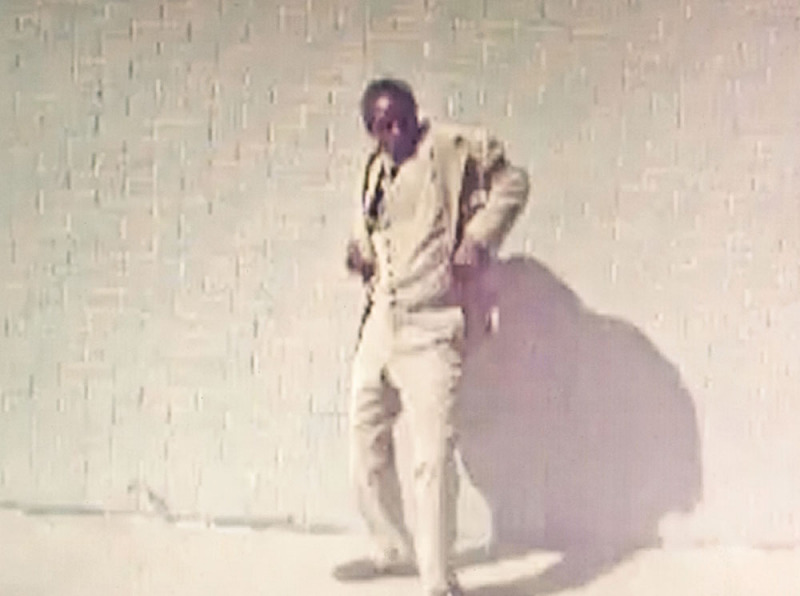

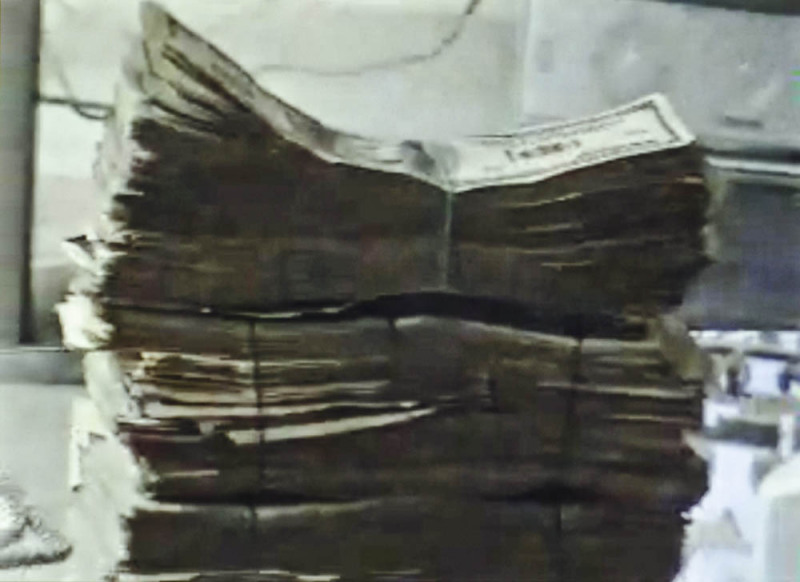

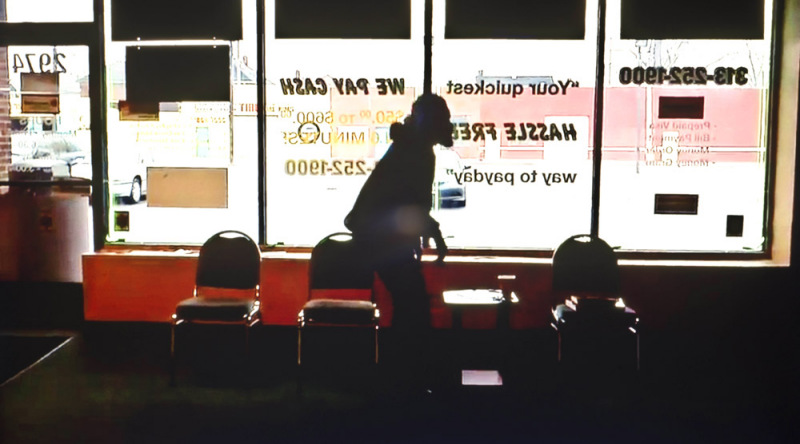

“It is wild, this ability for me to get in there and navigate other people’s camera’s and hijack what I want. It is very dark and enigmatic. It is in this low light and darkness that I found ‘my’ aesthetic and my beauty… the breakdown of the digital resolution then became something gorgeous and powerful – and it allowed me to take away the identity of the subjects and let them speak for American machinations rather than individual stories.”

Probably the hardest trick for any photographer to pull off following the publication of a successful first book is the second. The ‘second album syndrome’, as they call it in the music business. Doug Rickard’s first book, A New American Picture from 2011, was not only one of the best photobooks of the last few years, it established him as a significant new voice in American photography. It wasn’t the only volume recently to feature images made from photographing off Google Streetview, but it is surely the most important, partly because Rickard’s pictures were so damn good, referencing (but not slavishly) most of the best American street photography from the past forty years, but also because Rickard did not forget the basic premise of photography – which is to comment upon contemporary life.

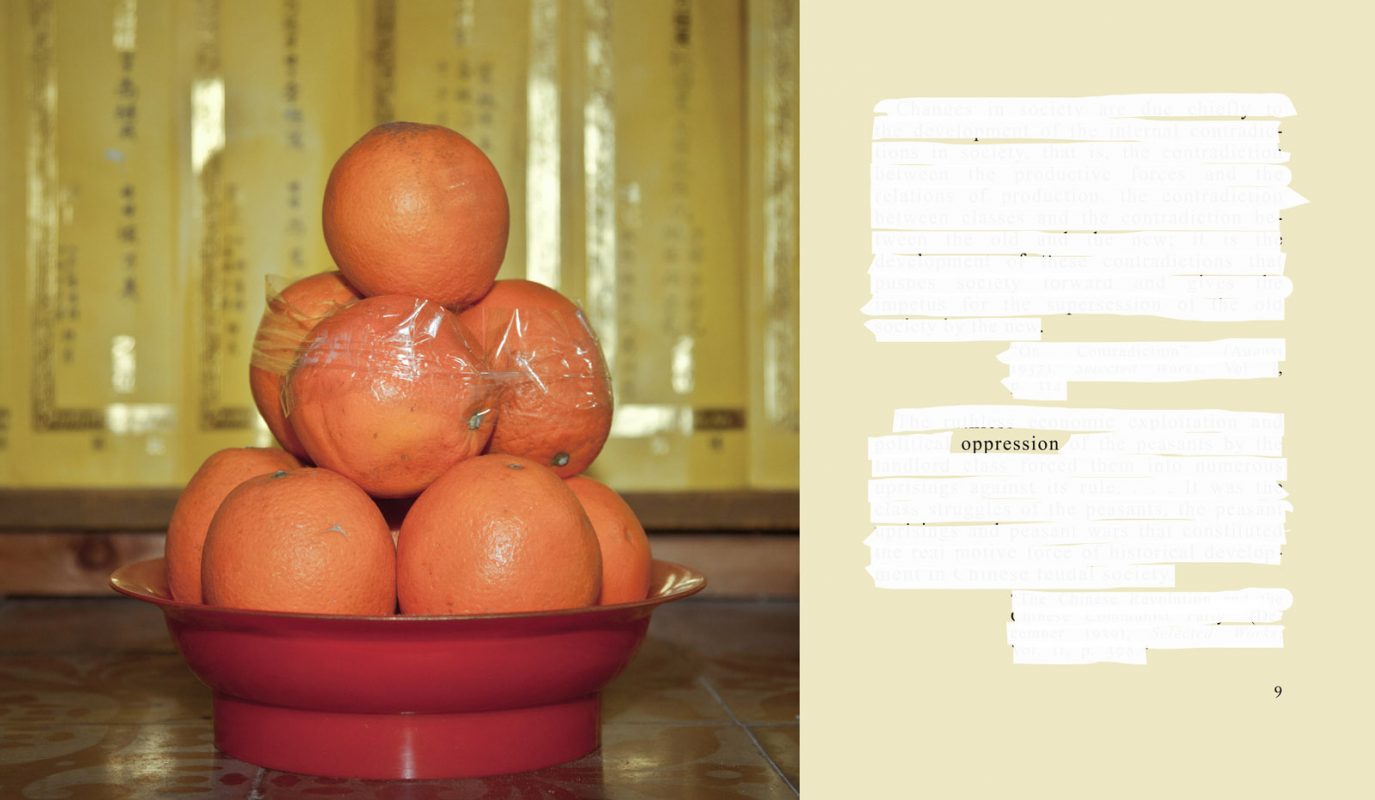

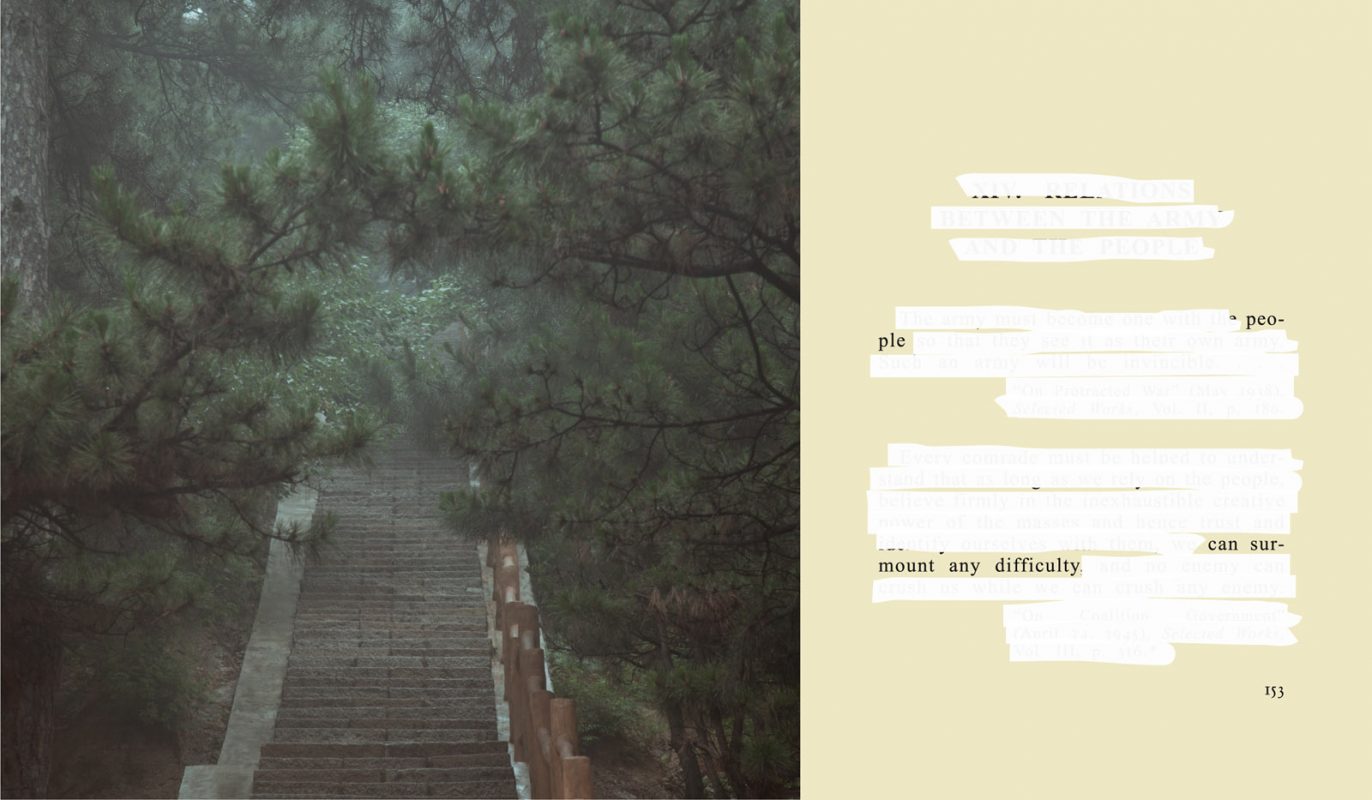

The book simply did not explore some of the issues centring around photography on the Internet in general – and Google’s ‘Big Brother is watching us’ in particular. It was also, as its title suggests, about a vision of America. Like the best photobooks, it pushed the medium’s boundaries, while at the same time gave us salient facts about today’s America. By means of Streetview, Rickard was able to ‘travel’ to places where it might have been difficult for him to take photographs in person. ‘The other side of the tracks’ it is called, dating from a time when America was much more segregated than today, and, especially in the South, the railway tracks often defined the boundary between racial neighbourhoods.

Although one would not stress the sociopolitical aspect of A New American Picture too much, it was definitely there, and although the book can be (and was) viewed in formalist and media terms, the documentary aspect was also important to Rickard, who has a particular interest in the Civil Rights period of American history.

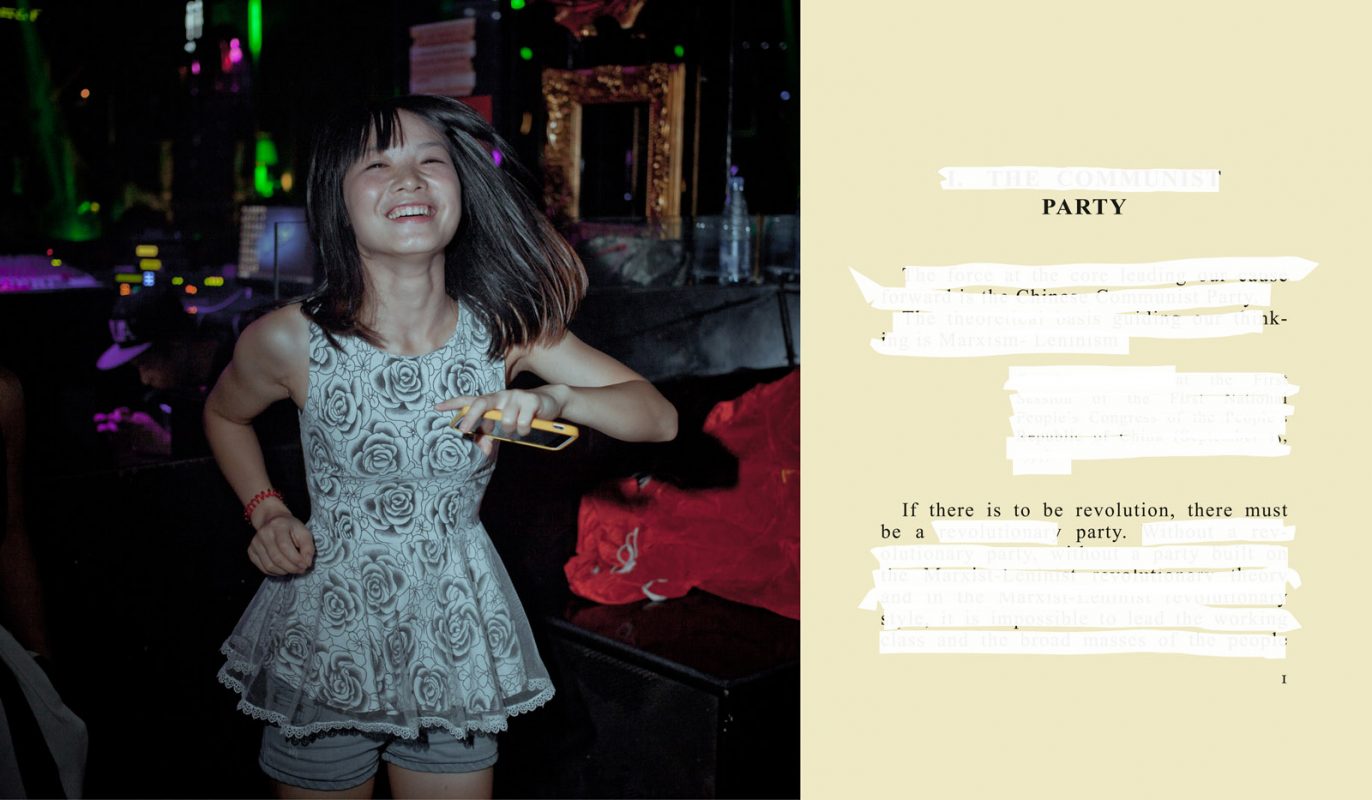

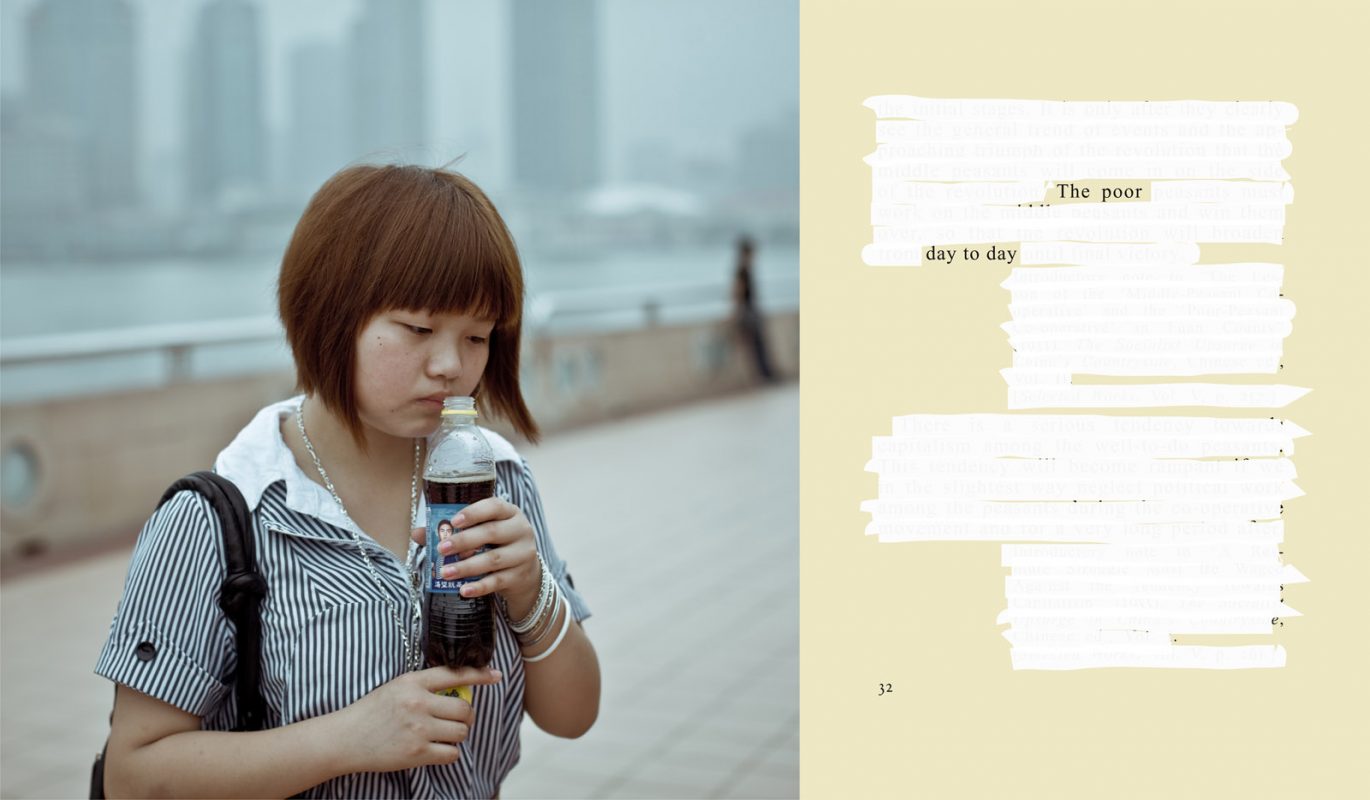

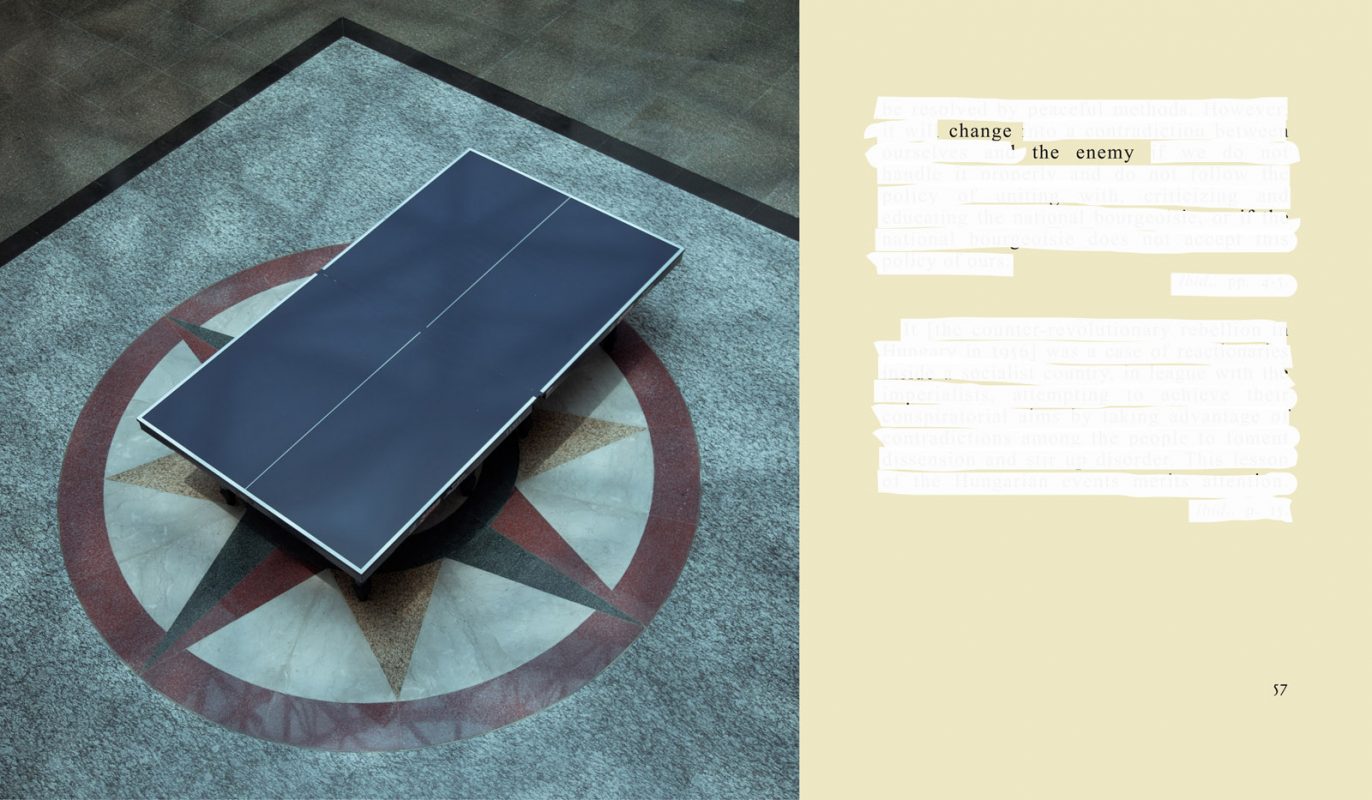

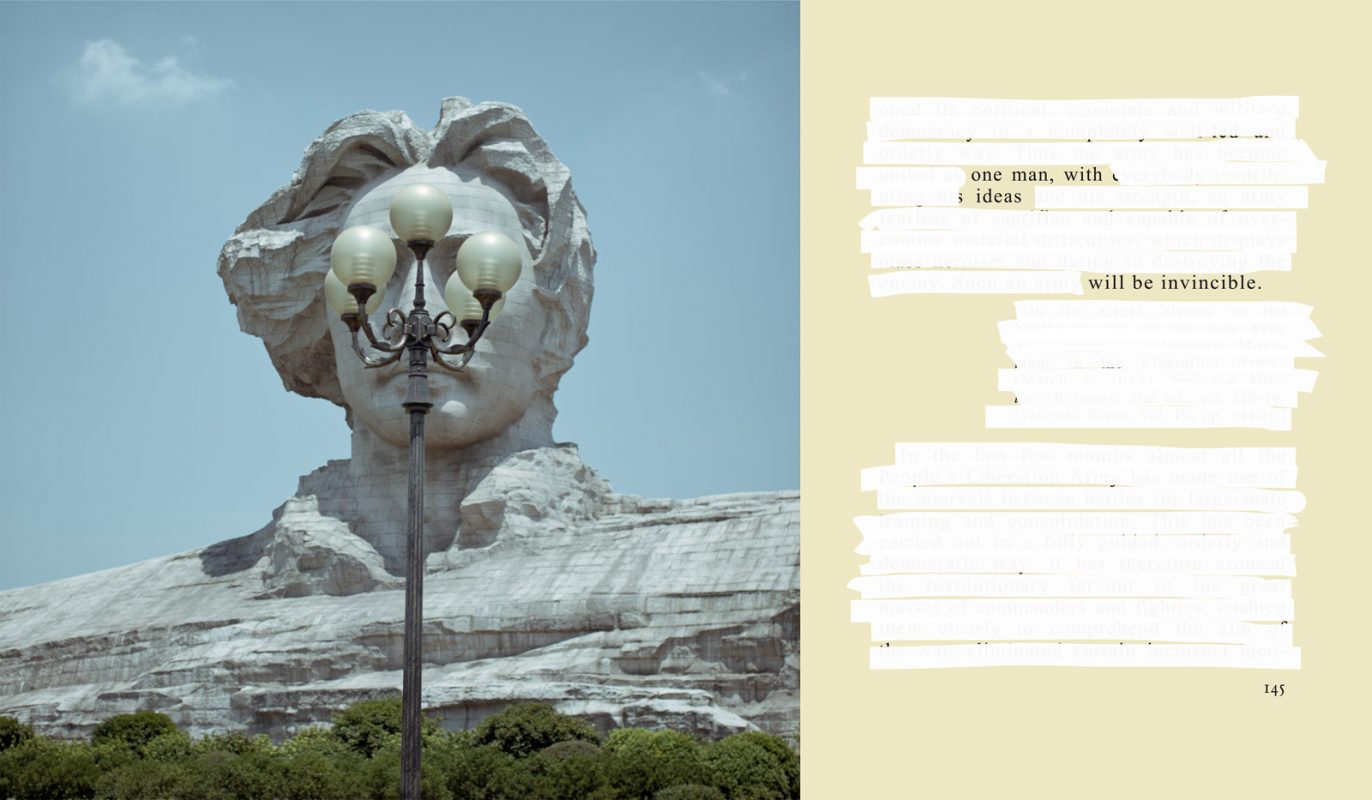

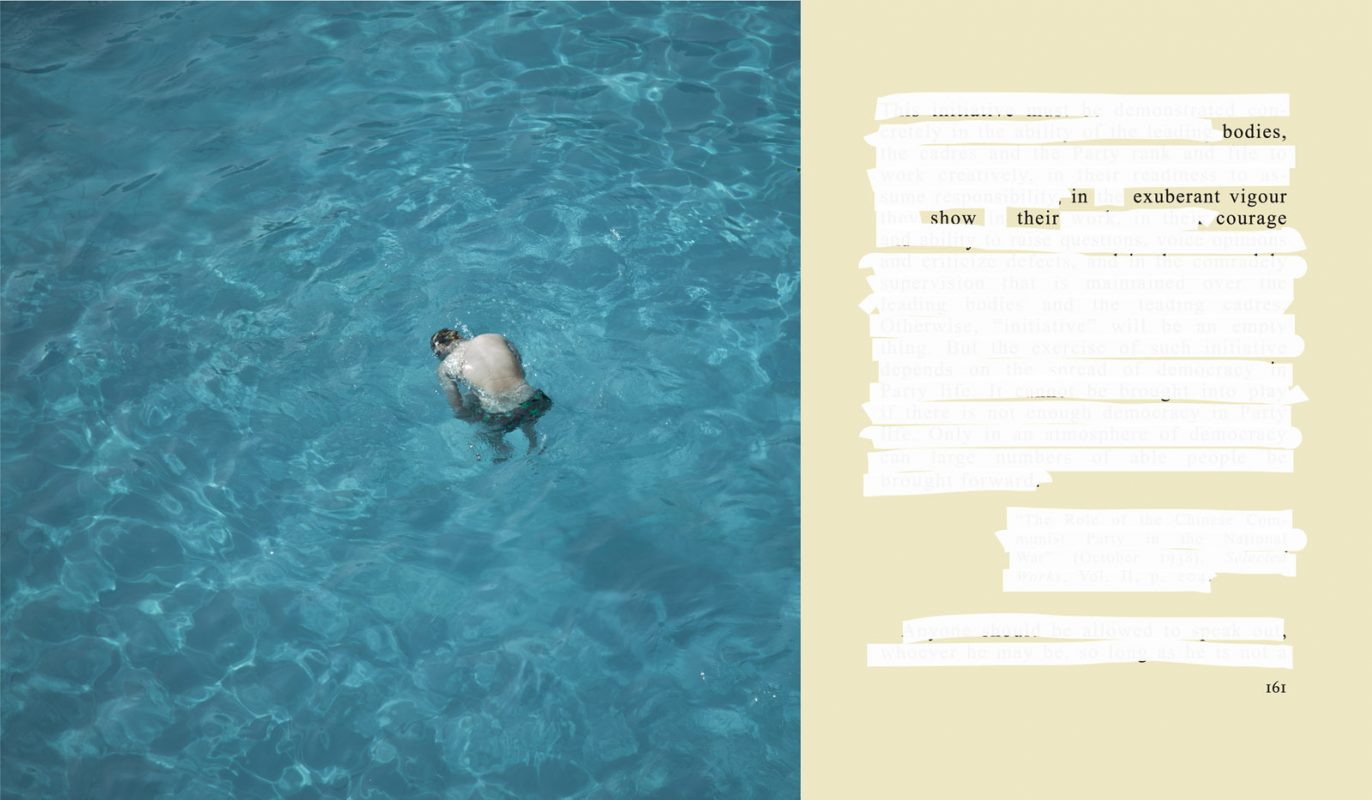

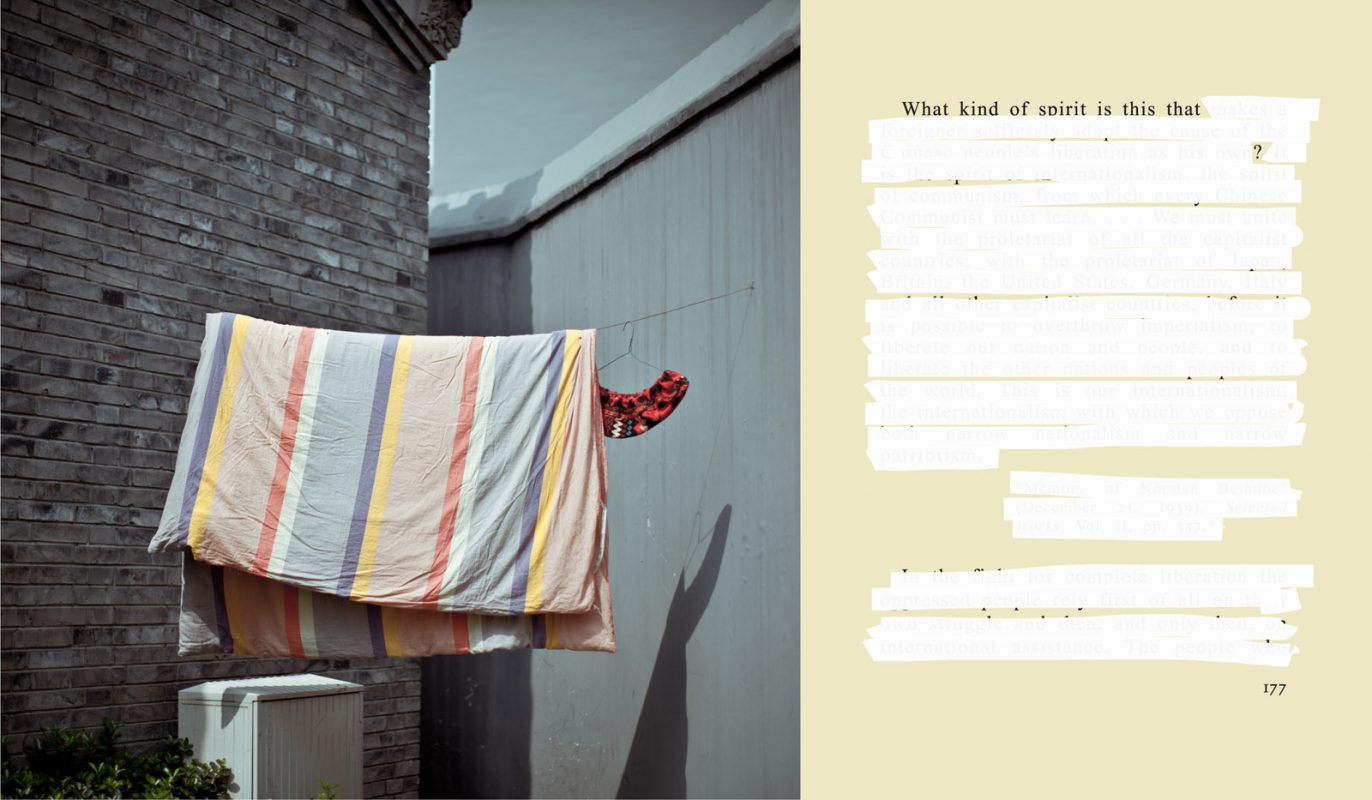

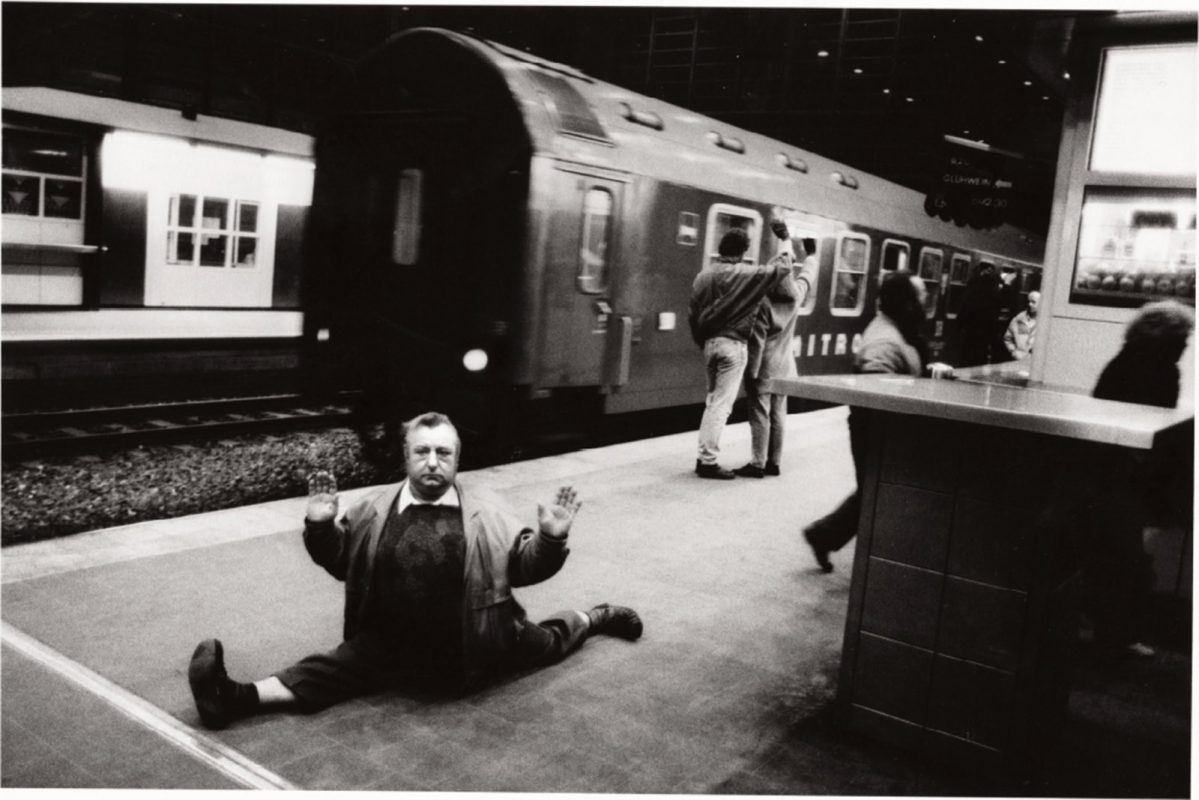

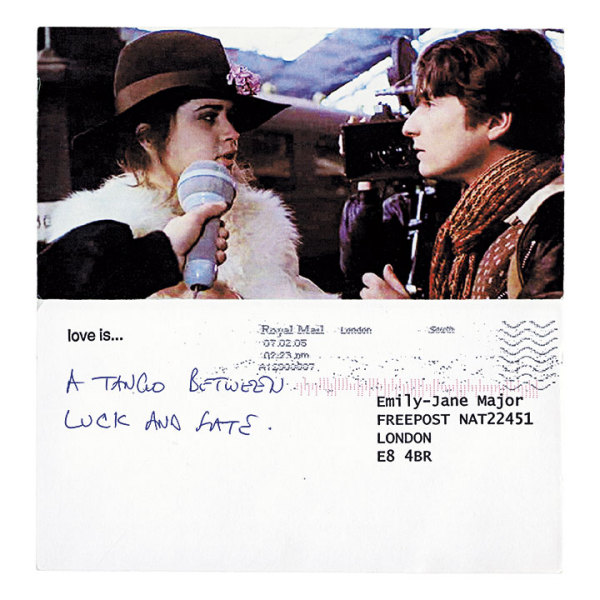

What is clear is that Rickard is part of a generation of American photographers who, without particularly shouting about it, have been documenting the state of the Union during the recent recession, and when American society, for various reasons – including implicit racism against a black president and the rise of China, as well as economic downturn – is suffering something of an identity crisis. The sense that there are two Americas, one definitely on the wrong side of the tracks, continues in Rickard’s new book N.A (the title stands for National Anthem), which continues the current tradition of American documentary photography, essentially telling stories about the country. And Rickard’s story is bleaker, and angrier than most. But ‘documentary’ – is this quite the way to describe a book largely compiled from blurred screen grabs from You Tube videos?

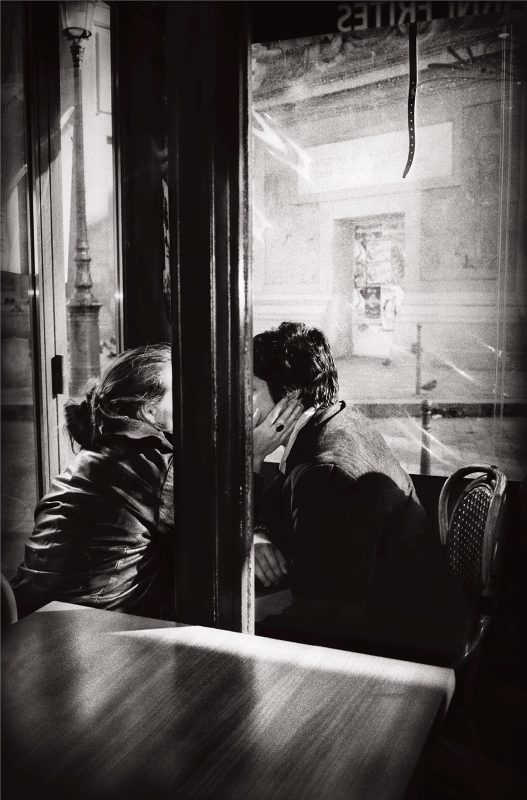

It’s always been a difficult genre to define. Walker Evans was always careful to talk about photography in the ‘documentary mode’, and the term ‘telling stories’ seems apt, in regard to Rickard’s work in general and this book in particular. In N.A, Rickard takes his imagery, from various Internet sources – mainly non-commercial, personal videos posted on You Tube. It might be described as ‘constructed documentary’, but then much more documentary is constructed than we might care to admit. As John Gossage has remarked of photography in general, “It’s all fiction anyway.”

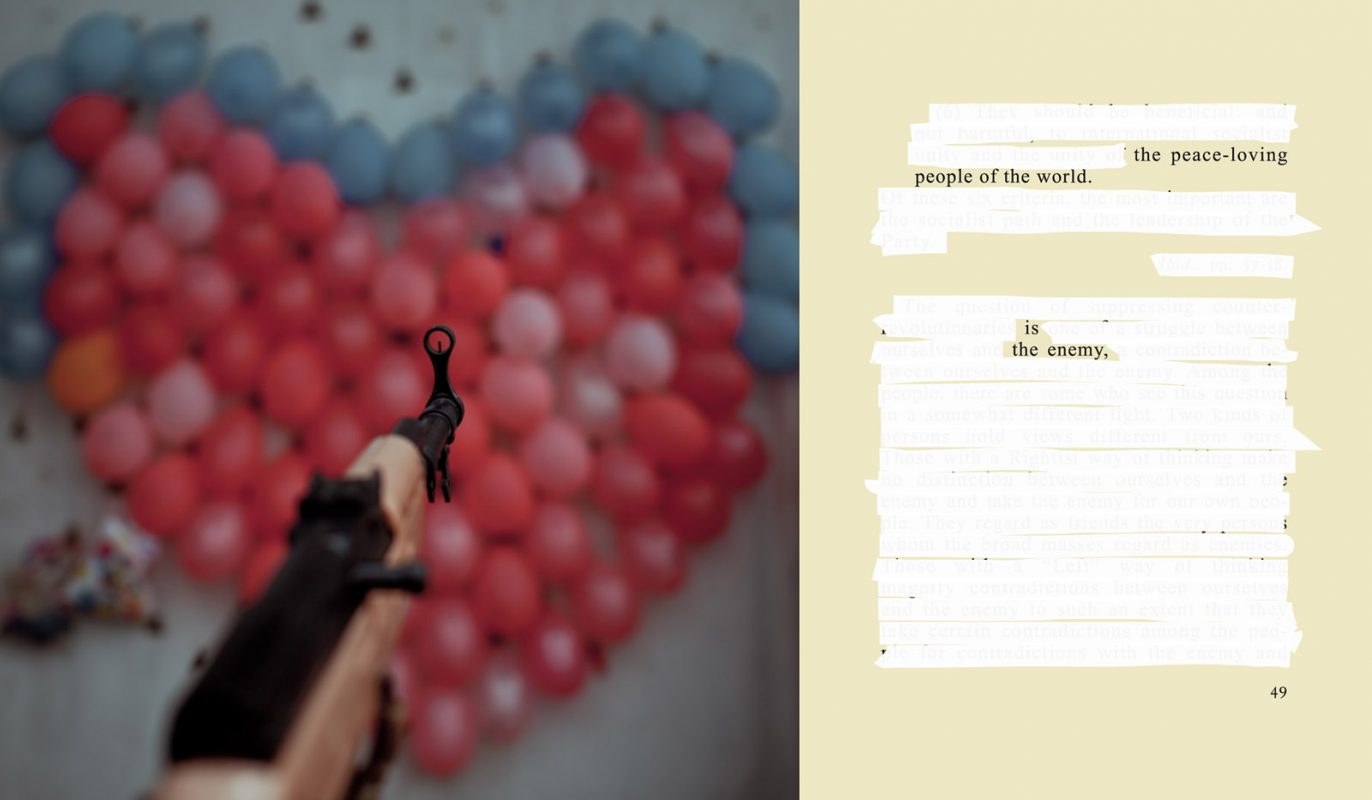

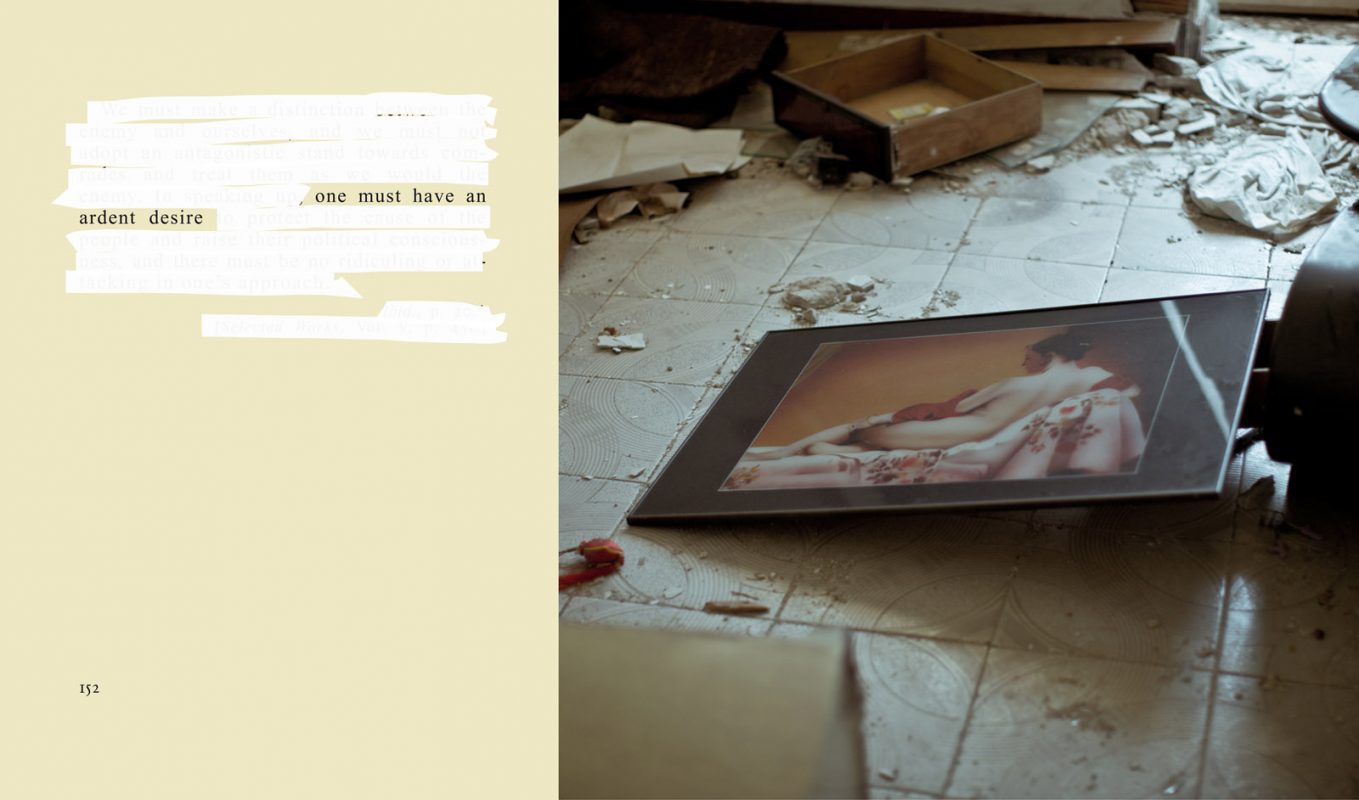

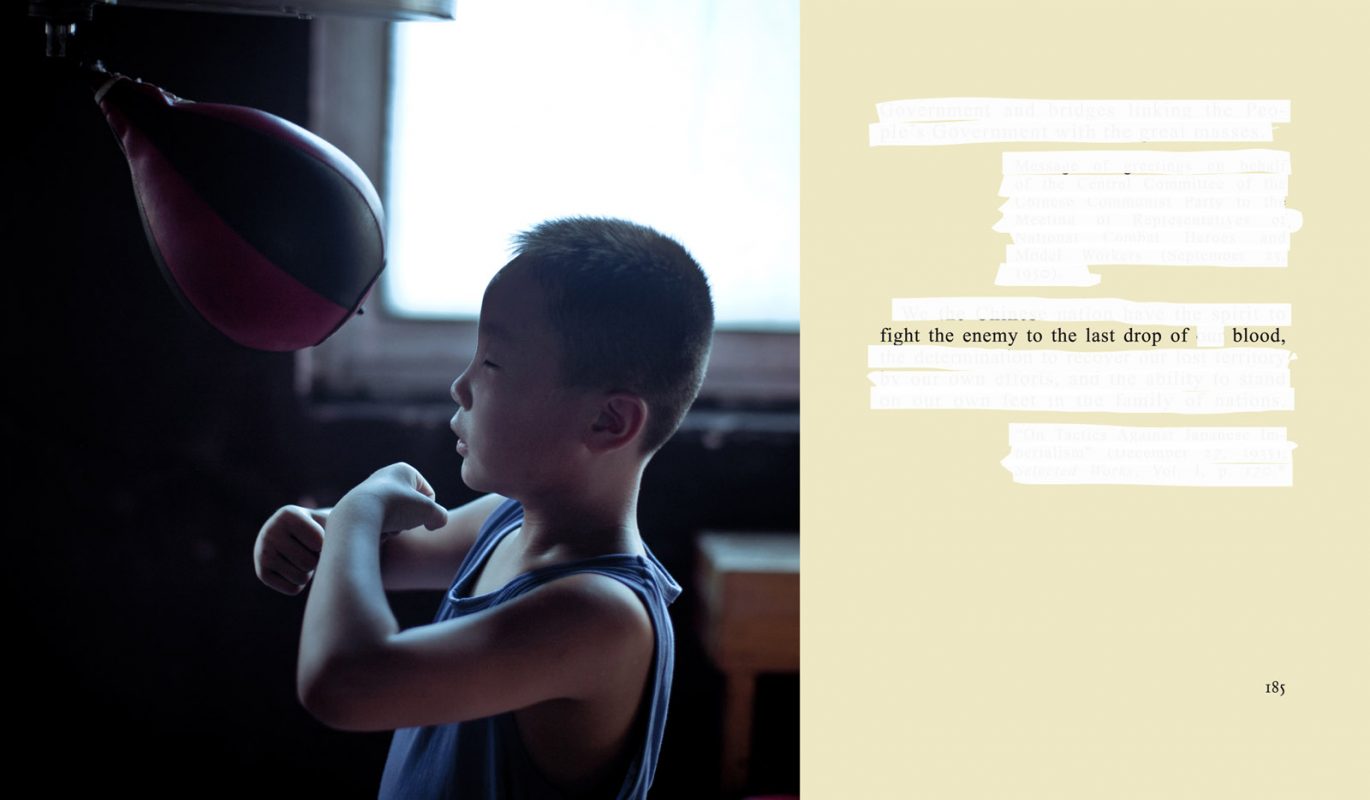

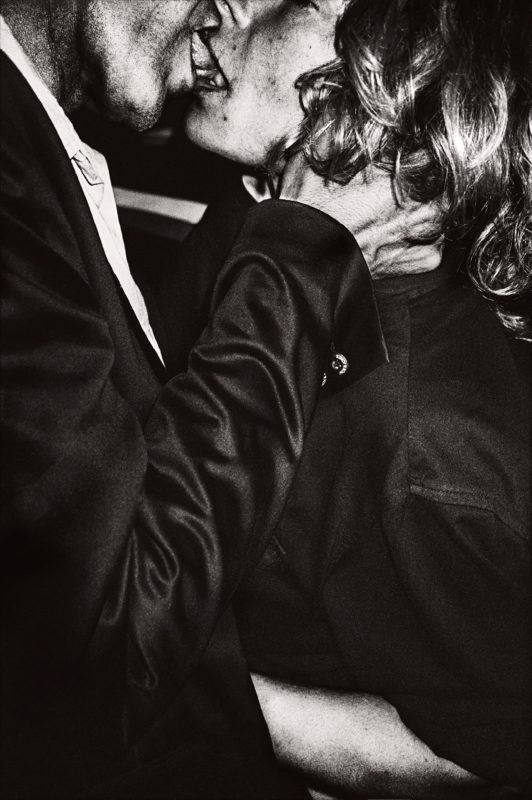

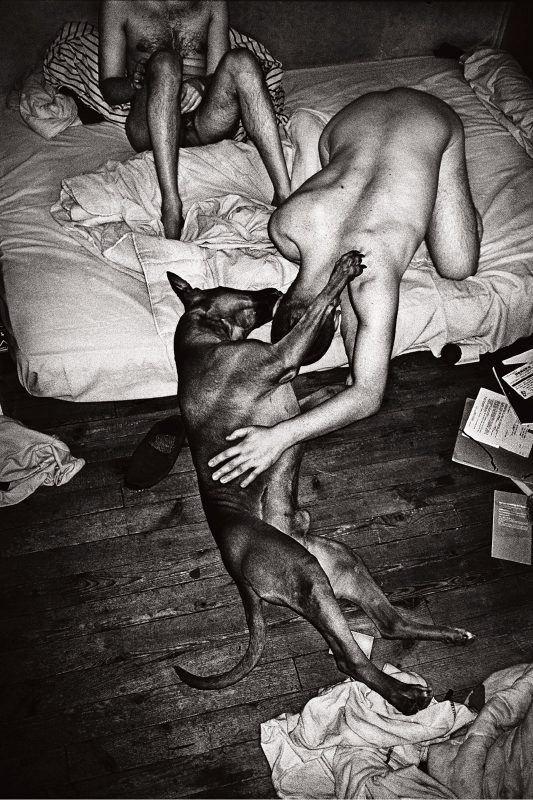

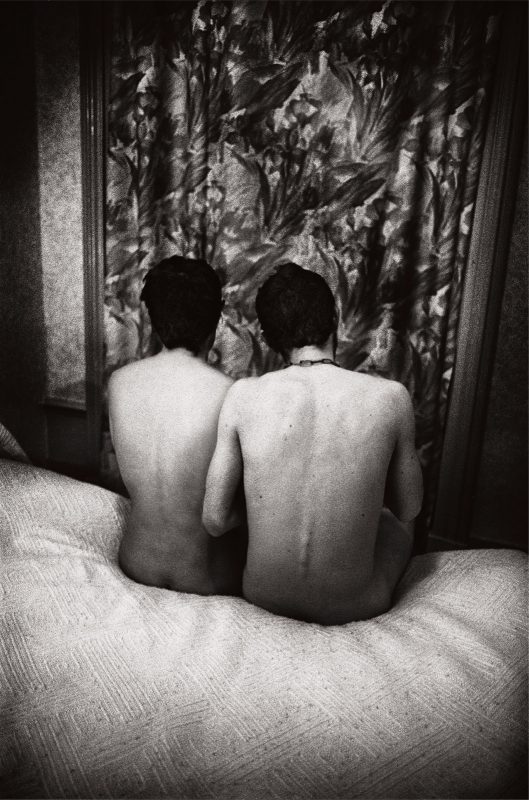

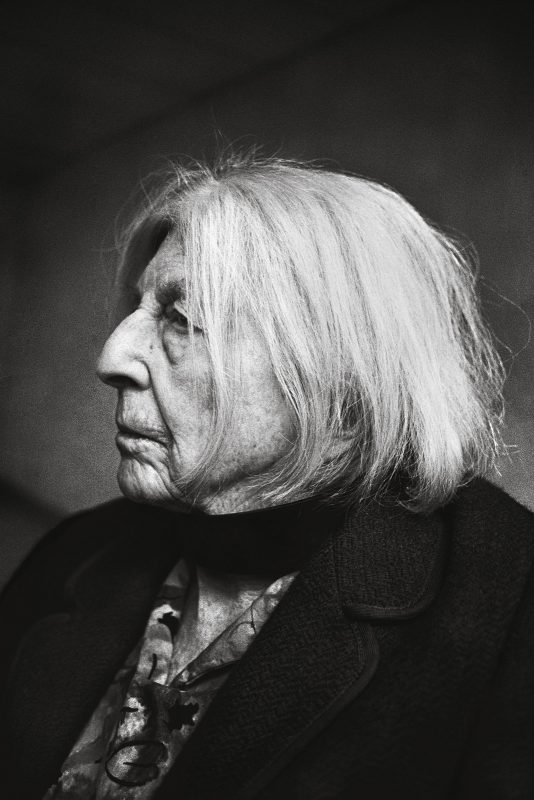

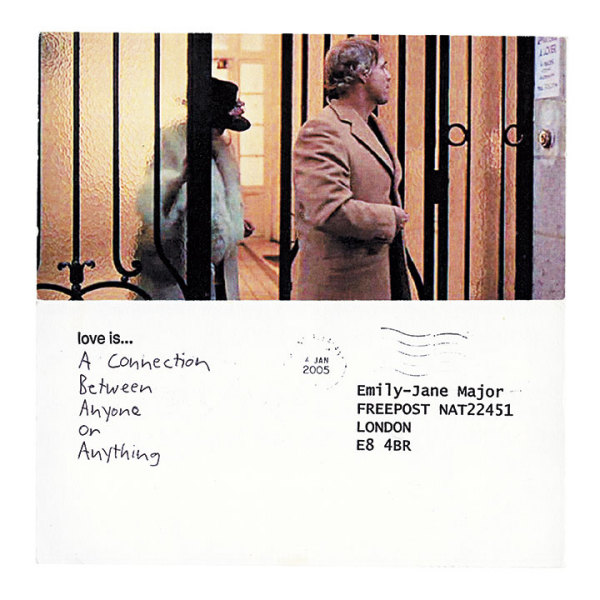

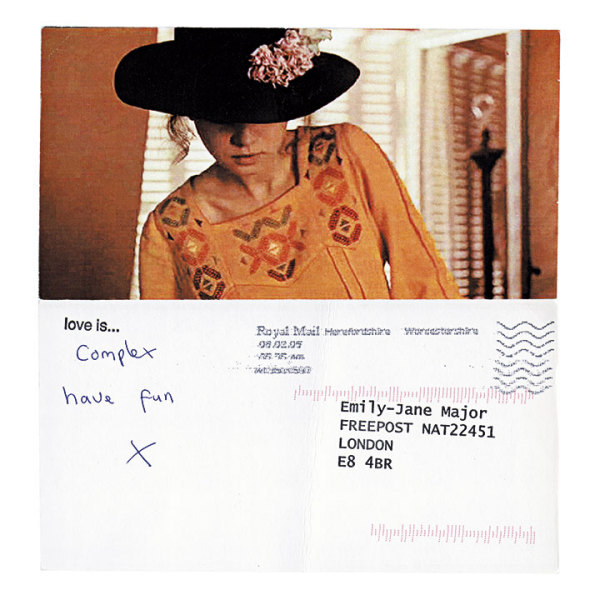

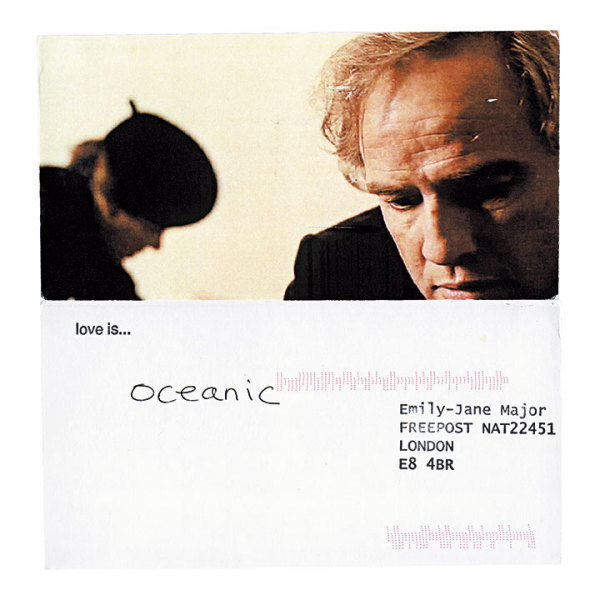

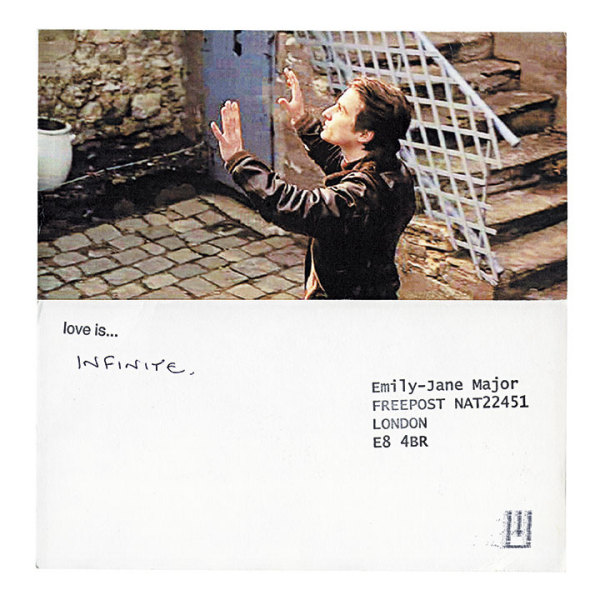

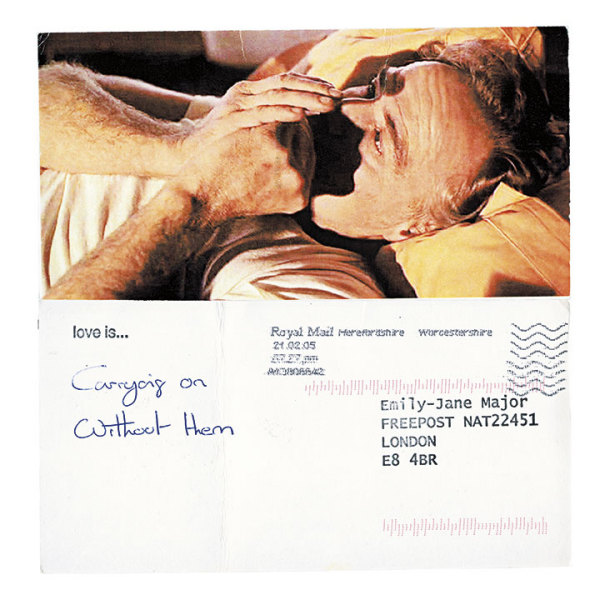

Keeping that tricky word ‘fiction’ in focus, in N.A Rickard seems to have reinvented the ‘photo-romain’ – the photo-novel. And just as that 1950s European genre influenced Japanese photography and the Provoke movement, N.A has more than a whiff of Provoke about it, especially in terms of its wildness and indeterminacy. N.A is a mood piece, but a very superior mood piece, all sideways glances and half lights. N.A is street photography, but not as we know it. It is street photography as might be practiced from an unmarked surveillance car, or someone being sneaky with a phone camera – and God help you if you’re caught.

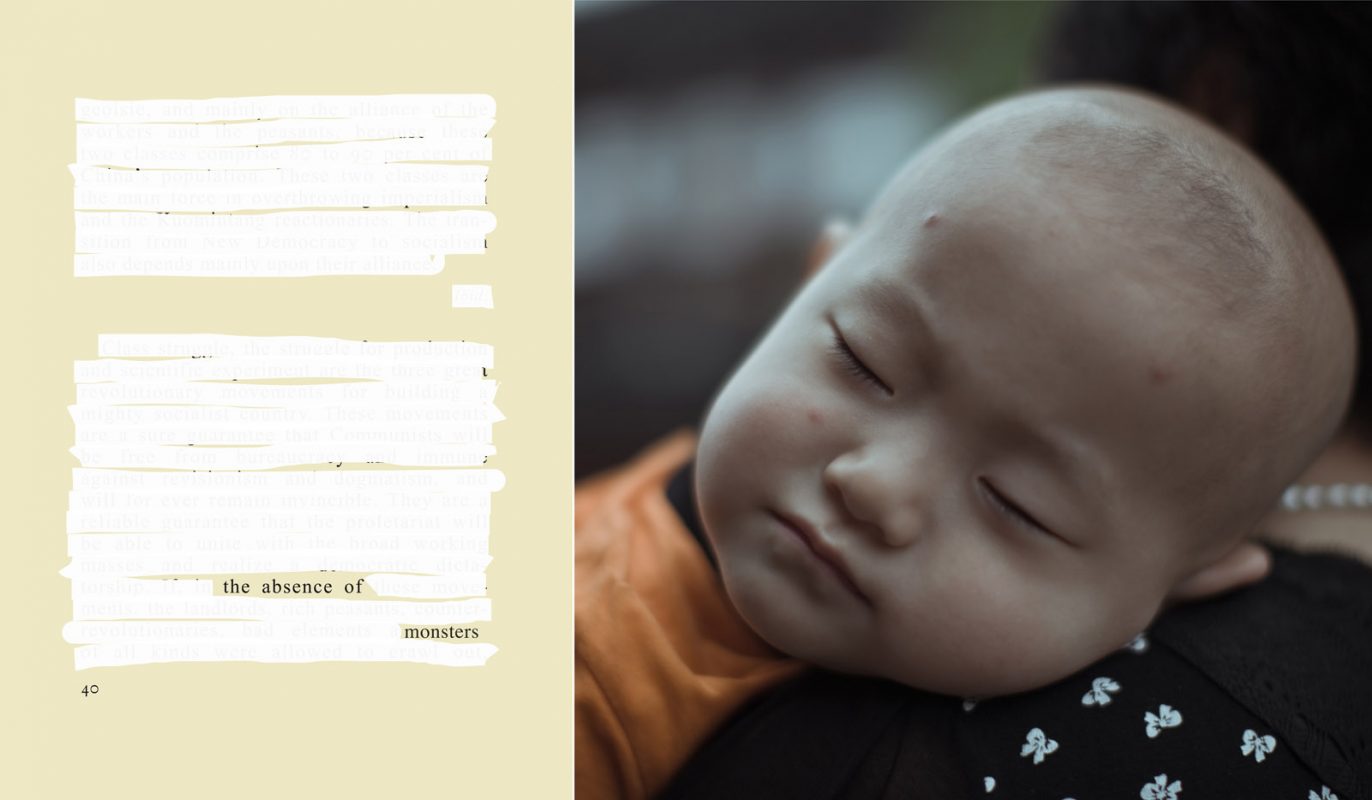

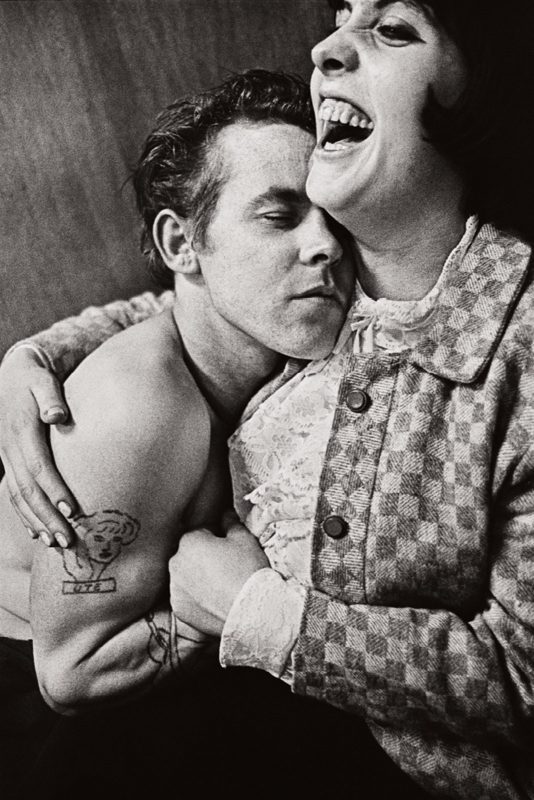

Here, we are in the territory of such gritty American crime TV series like The Wire, a world of flop houses, seedy bars, and crack dens – and of course street ‘characters’, some with guns, some hooded, most desperate. One hooded figure with a beard in particular looks as if he had strayed in from Paul Graham’s a shimmer of possibility. This is similar territory, but whereas Graham was contemplative, Rickard crackles with menace.

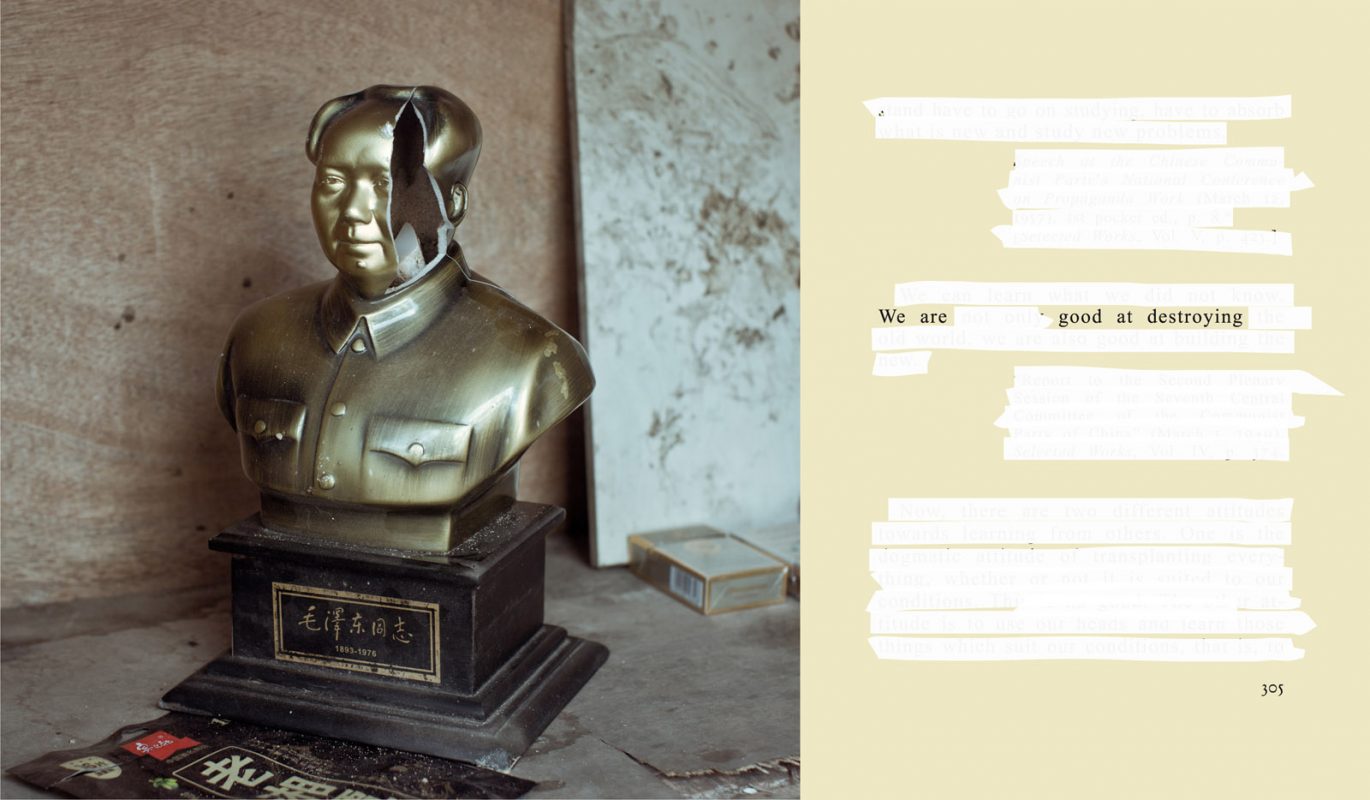

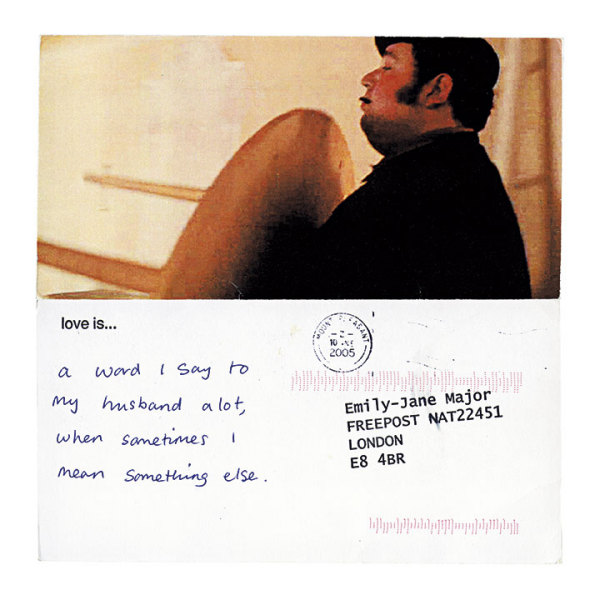

Some might feel that there is too much menace, whether mock or real, and that these images are a series of stills from a Hollywood movie rather than a photobook. That is to say, it is perhaps too melodramatic, too posturing, in the way of the videos he draws from. And yet, the very people he depicts take many of their attitudes to life and body language from fictional depictions, whether from film, You Tube, or gangsta rap.

Art imitates life which then imitates art, in not just an endless loop, but these days an almost instantaneous loop, so the question of what came first, life or art, becomes completely blurred and confused. And certainly one thing that N.A demonstrates is the confusion of life, the confusion between hope and despair, between freedom and servitude, cause and effect – and the fact that in the ‘land of the free’ many people lead lives constricted by politics and economics.

We rightly should be wary of too much fiction in photography, but if it is put firmly at the service of truth, the constructed documentary can be a powerful tool. N.A is an interesting new departure for Rickard, except it seems that it was in the pipeline all the way. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist. © Doug Rickard

—

Gerry Badger is a photographer, architect and photography critic of more than 30 years. His published books include Collecting Photography (2003) and monographs on John Gossage and Stephen Shore, as well as Phaidon’s 55s on Chris Killip (2001) and Eugene Atget (2001). In 2007 he published The Genius of Photography, the book of the BBC television series of the same name, and in 2010 The Pleasures of Good Photographs, an anthology of essays that was awarded the 2011 Infinity Writers’ Award from the International Center of Photography, New York. He also co-authored The Photobook: A History, Vol I, II and III with Martin Parr.